How many times do we need to be SoundClowned before we get wise?

Back in late December, tellingly/suspiciously right in the midst of the holiday vacation lull, SoundCloud started sending out the same sort of automated take-down notices to its users that YouTube has been using for years. Mix-style DJs and remix producers found certain of their uploads suddenly removed from circulation. According to an innocuously named audio detection algorithm, the tracks in question were allegedly guilty of infringing copyrights in their unauthorized uses of particular recordings. (Let’s not get distracted, I suppose, by the already stretchy notion that any of these things are substitutable “copies.”)

As Larisa “Ripley” Mann noted in the immediate aftermath, it seemed especially ironic that a site that so clearly courted users from across various DJ/remix communities — and, in turn, benefited immensely from said users’ (promotional) use of the service — would turn around and attack one of its core constituencies.

It’s ironic, but it shouldn’t be surprising. Because SoundCloud, like any other for-profit venture, is first and foremost looking after its bottom-line, of course it doesn’t assume the burden of contesting any of these assertions. Rather, per the DMCA, in order to remain in “safe harbor” territory, it complies with the data-analysis and auto-serves takedown notices. (And to its credit, again following YouTube, the company at least alerts people to the possibilities of submitting a “counter notice.”) This is, of course, reasonable behavior by a commercial company seeking legal cover against a content industry that has been known to drive similar platforms into the ground. But it’s not the sort of stance that is going to make SoundCloud the people’s champion (and ubiquitous audio app) it would like to be.

Despite the bloggy/tweety fallout, however — again, see Ripley’s round-up — SoundCloud has hardly seen its image tarnished in the wider world: last month, just a week or so after the first SoundClownings came to light, it was announced that the company had raised $10M in venture capital, and just yesterday I saw reported that the site has grown by 50% in just the last three months, now exceeding 3 million users. Far as I know, none of the users who allegedly gathered “in 517 cities around the world” for a “Global Meetup Day” earlier this week voiced any sort of discontent.

And so we bear witness again to platform politricks at work — once more with chilling implications for everyday musical practice, global popular culture, “fair use,” and the public domain.

So what are those of us who want a better platform to do?

I’d say there are two main options, which we might think in terms of tactics vs. strategy: 1) continue to support and invest in SoundCloud while pushing for a more robust defense of fair use there; or 2) build something else, something more able to resist the corporate enclosure produced by overzealous, automatic, and often erroneous copyright litigation.

Here, I’m going to propose a little bit of both.

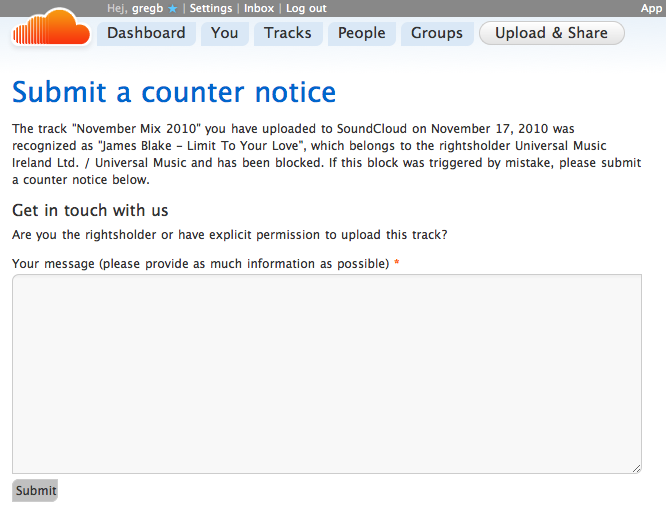

Amidst all the SoundClowning last month screenshots like the one above hardly seemed to present a reasonable set of choices for people who’d like to defend ordinary DJ/remix practice. All the assumptions are clearly running in the wrong direction. (“Recognized as”? “By mistake”? “Explicit permission”?)

Honestly, how is one supposed to respond? And how is one supposed to respond honestly? It’s not that the detection of the Blake track is a “mistake” exactly, but the assertion that the Blake track is tantamount to the whole of the upload is wrong. Moreover, implying that one must have “explicit permission” to use the Blake track presents a false and dangerous picture of the scope of fair use, radically restricting the realm of the legally permissible. Because this is how things are structured — as captured in the form above — there exist few practical alternatives for someone like gregb. He could file a counter notice and fight it, perhaps all the way to a costly and potentially bankrupting trial. (Is this really a practical alternative?) Or he can sit by and watch his mixes disappear one by one. C’est la net.

These issues aside, the screenshot invites us to reflect on how SoundCloud, and mixes like gregb’s, contributed to the rise of James Blake. (Is it just me, or is it extra ironic that Blake’s aesthetic push toward conventionality accompanies a rejection of experimentation at the level of music industry?) Or we might think about how SoundCloud served as a launching pad for someone like Munchi, who really did exploit the site as a kind of launching pad, now garnering thousands of hits on his uploads. I wonder if it’s only a matter of time before astounding efforts like Munchi’s breakout year in 2010 — aided and abetted by a great many samples used without permission — become an impossibility on SoundCloud, as the company is brought to heel under 20th-century copyright law while attempting to host 21st-century audio culture.

Of additional worry, as highlighted in this TechDirt post, is the question of whether we should assent to automated processes adjudicating the various downstream uses that our constitution protects by granting a “limited monopoly” to copyright holders. The author of the post, Mike Masnick, calls this the “Automated Diminishment Of Fair Use,” and I hope that sounds as scary to you as it does to me. Despite that the audio-detection algorithms have already proven error-prone and predictably grabby, we’re letting bots decide what is fair — or more to the point, what is not.

Should we really cede that ground? Is that a good trade-off for the network effects of a massive socially-networked media-sharing site? Plenty seem to think so, and act accordingly, even if their concession is implicit.

Ah, sample-based music in the age of algorithmic detection! Won’t this be fun. We can play it like the 1990s all over again, when torch-bearing “underground” sample-based hip-hop producers like Primo, in the wake of chilling litigation, managed to stay one step ahead of the system, taunting catalog companies with dusty samples that weren’t easily recognizable even by hired-gun sample-sniffing snitches. Here’s an open letter from 1998’s Moment of Truth that still resonates:

[audio:http://wayneandwax.com/wp/audio/primo-rant.mp3]

In that vein, I present to you a remix (or two) of the very James Blake track responsible for some recent disappearances on SoundCloud, as mashed-up with its source of inspiration, Feist’s original, in a couple different ways. (As it happens, I opened a SoundCloud account two years ago this month, but this is the first time I’m uploading something.)

In a gesture of fairness, if you will, I decided to make two versions of the Blake-Feist mashup, one that keeps intact the cover and bends the original toward it, and another that performs the opposite procedure. I like the idea of “honoring” both versions in this way. (They get to have their integrity and we get to eat them too!) I myself have a preference for slowed-down female voices over sped-up males, but I’ll be curious to hear if anyone prefers the Feisty, chipmunky Blake version.

Without further ago, here are a couple of those trademark orange waveform widgets:

Limits to Your Love (Blakey Version) by wayneandwax

Limits to Your Love (Feisty Version) by wayneandwax

A few technical notes, as always, about what I’ve done here:

1) the two versions are several semitones apart, but more or less the same tempo, so all it took was some pitching up of the Blake to meet the Feist, on the one hand, and some pitching down of the Feist to meet the Blake, on the other

2) as you can see in their Vimeo instantiations (Blakey | Feisty), I have, in each instance, left one of the tracks completely whole while applying as few cuts as possible to the other; this required relatively minimal surgery, as the only real difference, time-wise, was Blake’s inclination to stretch things out, as in the intro

3) the Feist track actually has a long-ish intro that I, following Blake, completely bypass on each mashup; I saw no reason to begin the Feisty version with a Blake-free minute of music, though I did, in a departure from my generally hands-off approach here, suture some of the Feist intro to the long, almost silent section of the Blake version (as you’ll see/hear)

I hope both mashups do the job of drawing the listener into the questions of form, interpretation, and affect raised by these subtly divergent but simultaneously-sounding renditions. Let me be clear: I’m not pretending that these remixes are necessarily aesthetic triumphs; indeed, I think they both get a little muddy half-way through, especially once Blake starts getting freaky with the bass — but that sort of disjuncture is precisely the sort of thing that mashups like these are so good at highlighting. As I’ve argued elsewhere, mashups can offer poignant, useful resources for classroom discussions of form and content, not to mention re-use and fair use, self and other, etc., and it is in the twin spirit of education and critical commentary that I defend these tracks if they happen to be sniffed out by some clumsy algorithmic audio-sleuth.

It may go without saying, but I want to note that I’ve been posting mashups just like these — almost always of songs and their kindred “cover” versions — for many years now, first at (the now defunct) Riddim Meth0d, then on my own site and more recently at Vimeo (where I can show the two tracks playing concurrently in Ableton).

I’ll be curious to see whether my remixes can weather the sample-sniffing. I’ll be sure to keep you posted. Feel free to join me in a little bit of digital civil disobedience / remixxy fun!

Pro-tip: parodies are almost always a safe bet —

(h/t gregb)

If I still have your attention, please allow me to briefly discuss plan B: i.e., rather than working from within SoundCloud — tactically, if you will — to resist spurious copyright policing, we instead seek a new way forward, a strategy for ensuring a certain sustainability and resilience for collective, interactive musical practice, for our peer-to-peer industry. Given the direction the White House appears to be heading with regard to “IP” and the increasingly pernicious and vicious legal tactics of the content industry, there is a clear and present need for better platforms on which to stage our shared culture.

Decentralization seems key. And it’s telling that much of the discussion in the wake of December’s SoundClownings came around to the obvious limits (despite the advantages) of massive corporate media-sharing sites. Channeling hip-hop in his own way, Timeblind reminded that “only toys buy their paint” and, hence, “pirates need to keep it on the D/L.” I hear him on that, but at the same time, I’m not comfortable ceding the high ground to the vested interests who have decided what is “piracy” and what is not.

I appreciate that Joro-Boro’s digestion of the discussion brings our focus back around to Rozele’s critical questions as left in a comment on my “Platform Politricks” post:

what are other ways of having platforms of these kinds, which place their control in the hands of the folks who use them? and, more importantly, perhaps, what are ways of propagandizing these autonomous platforms, and of spreading the analysis that works against the continued use of the current corporate ones?

Her sentiment was echoed very closely in a comment Jace “/Rupture” Clayton left on Ripley’s post:

I’m wondering what it would require, technically, to start building decentralized control of our resources/platforms/online communities. What was the best, more successful aspects of an Imeem or Soundcloud + how can we start assembling + using alternatives?

In the week or two following the SoundClowned episode, a few of us were chatting about the different pieces necessary to the puzzle. Tim “Tones” Jones proposed some ideas over here, and we chatted a bit in the comments, but I’m sorry to say that, once again, the conversation has since tapered off.

I wonder, is it already too late to move from this moment? Has the iron cooled too much? That would be disappointing. As Rozele put it in a follow-up, “before some other corporate pseudo-solution starts lying to our friends,” we really need to answer some concrete questions, e.g.:

how many folks who’re being evicted from SoundCloud will put up some cash to kick things off? and, more importantly, how many music-makers will commit to making this new space the only place to find their work online (or at least the primary one)?

There are, of course, major tradeoffs between scale and resiliency, and these same questions we’re asking of each other open into broader, current, critical debates about resiliency on the net. In this regard, we might see something like Wikileaks suggest some options for music culture in the embrace of an “alternative control structure.”

The comparison is not so far-fetched. See, for example, a recent piece by Clay Shirky, who trots it out:

Like the music industry, the government is witnessing the million-fold expansion of edge points capable of acting on their own, without needing to ask anyone for help or permission, and, like the music industry, they are looking at various strategies for adding control at intermediary points that were previously left alone, under the old model.

With dovetailing interests like these, maybe Somali pirate servers are our best bet after all.

Seriously, though, who’s gonna step up and build something? Are 4shared or Hulkshare the best we can do for scaling our (free) distro? Are pop-up ads and malware a necessary reality for the sort of peer-level music industry that seeks to evade capture? Do we really want to operate in a world where our own ideals, and values, and best practices must be compromised if we wish to continue making and sharing art on a global scale, in a public way? Must we be forced (back) underground, and coerced back into adopting practices that cut against our ethics, our desires to acknowledge as we build on the work of other musicians and artists and producers?

To return to Ripley (in a great follow-up post), there are deep implications for this sort of retreat-by-design:

Nameless reuse can erase the reality of difference, turning everything into a consumerist fantasy, where you don’t have to deal with the lived realities of different worlds and different lives.

Again, the big question is: will we rise to the occasion, and finally find a way to give the drummers some (and protect their legion interpreters), or will we continue to get clowned, and pawned, and toyed with?

The choice is ours.

What if remix culture boycotted corporate pop — said if you don’t put your music on CC or leave it open, we don’t buy, listen, share, put work into it? DIY used to mean more than DIY, there were other ideals too.

That would reduce certain liabilities, to be sure. Curious to hear what others think of such an approach — and it’s a little conspicuous that I’ve yet to really see this put out there as one viable, anti-corporate way forward. (Aside from, say, within the CC movement.)

For my part, while I see the pragmatic reasons for this, I don’t want to give up my (constitutional) rights to various kinds of uses of things, regardless of how corporately produced. Corporate pop is, for better or worse, and whether we or they like it or not, part of public culture, and we need to insist on our right to work with it without running such enormous risk.

The answer to bridging the gap between scale and resiliency seems to be platforms that allow one social networking site to communicate with another. Like how Hype Machine picks up Soundcloud feeds and Twitter displays Youtube videos.

One site that seems to be working towards this is Flavors.me, which allows you to display feeds from any of your preferred sites. It’s currently struggling with functionality and I don’t know if it has a networking function to connect with other Flavor.me users. I just use it as an example of a site that can introduce a smaller site to another with mor users.

If there we a tougher site, this type of site would be integral to reaching larger audiences. That, of course, is a lot of ‘ifs’.

I did get one of those message when uploaded my last mix. i really don’t understand the logic in this, as I’ve not actually mentionned any authorization, and still got a positive response the day after …

http://www.ground7music.com/2011/02/sunday-mix-001.html

Great post. And thanks for picking up on the idea that we should be trying to build an alternative network. Decentralized or hosted out of reach (politically or geographically)..

I’m with you on wanting to keep the right to mess with corporate pop. It’s shoved down my throat all day long, I think I should have the right to use it too. In general, part of creating is drawing on all the music that exists already, which isn’t cc-licensed. Especially considering CC licensing is mostly only used by people with a certain level of familiarity with licensing already (which leaves out most musicians).

Right now, if I restricted what I played to cc-licensed stuff it would be a short and/or crappy set indeed, unfortunately. But I do try to play a lot of music that my friends make. I don’t tend to check and see how they license it, I assume if I get it from them I can use it how I like (with limits, like not lying and saying I produced it). Once we get outside the circle of friends, I’m not sure licensing will work, I think the default rules need to be changed or we need to get on different networks.

as ever, thoughful and thoughtprovoking, both in the post and in the comments…

a little commentary, some of it critical:

i like your hop into the bullring with soundcloud, and like the idea of a lot of deliberate bot-baiting. seems useful, as publicity stunt and as a way of testing the structures they’re setting in place (on the legal and software fronts).

but while i see the first half of this in there

1) continue to support and invest in SoundCloud while pushing for a more robust defense of fair use there

i can’t see the second at all. and i’m not surprised, because i don’t see any way to do that – unless you happen to have an extra dozen million bucks lying around to buy out SoundCloud’s investors and venture capitalists with. otherwise, it’s the long slow road, because substantial change at SoundCloud is an after-the-revolution proposition.

let’s be clear. SoundCloud is a business. its policies come from its economics. to make it, economically, it will do what folks in power (politically and economically, as if there’s a difference) want. the example of Napster shows the bloodied stick; that of iTunes shows the PVC carrot. this is structural, not specific to SoundCloud – there ain’t no way out through that door.

which is why i’m excited to see the post turn to the how of building alternatives. but the question still stands: who’s going to be the one to say “i’m doing this – who’s in?”, rather than asking who’ll do it? if i were either a techie or a dj, i’d be on it. i’m neither, so i’m just gonna keep on gadflying from the dancefloor.

two more quick thoughts:

my (constitutional) rights to various kinds of uses of things

the vested interests who have decided what is “piracy” and what is not

well, i’d argue that standing on your constitutional rights is pretty meaningless unless we’ve already got the court system on our side. ‘rights’ (constitutional or otherwise) are a record of the balance of forces at the end of the last set of skirmishes – and i don’t mean legal skirmishes, i mean actual exercises of power. they’re the language that states use to insist that what they’ve been forced into was their idea all along. and to make it seem as if they can’t be forced to do things. ain’t no way out through that door, either.

relatedly: and, hell, if the state wants to rhetorically set us up as pirates and itself as the royal navy, we ought to be applauding. i mean, no one’s thought captain bligh was sexy since 1786; pirates get played by johnny depp… and pirates are so broadly culturally appealing that the u.s. government keeps trying to come up with another term for the somali freebooters so it can talk about them without making them look good. they want to hand us the cultural high ground, let’s take it. and thank peter lamborn wilson / hakim bey for getting it nice and ready for us…

Thanks again, Rozele, for being so rad.

You’re right that approach #1 is basically incrementalist and ultimately statist — blame the mischievous pragmatist in me — and I suspect you’re also right that there’s really no true freedom or satisfaction or empowerment to be derived from working within that model, corrupt as the courts and legislature have become. (And this is why Lessig has shifted his own focus from copyright to corruption.) Indeed, this sort of incrementalism is a big reason why even Creative Commons leaves us wanting, as it essentially upholds, as it works within, a status quo that seems deeply flawed. (Plus, here’s something: SoundCloud doesn’t even give one an option of reserving no rights at all, of explicitly putting your material into the public domain, even though Creative Commons itself has implemented such a scheme.)

Initially, my draft of this post included a variety of links to various distributed file system schemes that people have been working on. It does seem like the technology is already there, or almost there, for this, and it’s just a matter of some hard work and implementation. (And, then, as you remind, there remains real work to be done with regard to adopting, promoting, and championing this approach.) Along these lines, this piece in today’s NYT about the “Freedom Box” seems quite promising.

Also, in the immediate wake of the SoundClownings, a few of us were indeed plotting — via email, comments, and chatrooms — about how to go about building an alternative. For instance, Tim/Tones pretty quickly worked up a player that looks a lot like SoundCloud’s (and maybe even a little nicer). In our email exchange, he wrote:

And while some things, like the player, appear easily engineered right away, others — such as making it easy for people to adopt/install and network — seem a bit more challenging. Where do we go next with this?

Unless it’s unclear, I’m totally up to the task of helping to organize and engineer this thing. My limited coding skills aren’t exactly going to be so useful, but there are lots of friends out there who can help. I guess it’s still not clear to me how to make the rubber meet the road here. I suppose a dedicated team, and a bit of Kickstarting perhaps, would be all we’d need.

TAZ4LIFE!

Just came across a post that speaks nicely to the discussion here: “Thoughts about a Pirate Internet”

see also, this recent piece by Douglas Rushkoff (that I was led to by the link above) — pull quote:

Wayne, Soundcloud was a TAZ… remember what the T stands for!

point taken. where my PAZ at?