Last week there was a message posted to the dancecult list, which, in the process of recommending a couple of Nate Harrison’s fine videos, asserted, not uncommonly, that the Amen break was “the most sampled rhythm ever, the very foundation of most rap, techno and jungle.”

Now, undoubtedly the Amen break is one of the most heavily sampled recordings since the advent of digital sampling, but I wouldn’t know how to begin assessing, quantitatively, whether it is indeed the “most sampled” break of all. (Let’s put questions of “foundation” aside for now, never mind what it means to sample a “rhythm.”) I’d like to take the opportunity, then, to raise some methodological questions, not to mention musical-ethical-technological questions, about the class of samples that have far outstripped their breakbeat brethren in terms of frequency and prominence. Such “breaks” — tho they’re not always breaks in songs, per se; some are full or partial instrumentals — essentially become basic building blocks, linked less to their initial recordings (for listeners and producers) than to the dozens or hundreds of other tracks that have also sampled them, hence accruing a kind of associational-emotional resonance deeply entwined with notions of genre and style.

Though he discusses its ubiquity (and submits that it has now passed into what he calls the “collective audio unconscious”), Nate Harrison never makes as bold an assertion in his video. Which is not surprising. The actual numbers are awfully hard to get at, quite elusive in their vast undocumentedness (and perhaps undocumentability, as I’ll discuss below). In the pantheon of well-worn breaks, the Amen certainly scores high — probably top three (as an “off the top” estimate), but who can say conclusively? I make my own estimate based on years and years of listening to hip-hop, jungle, and various other sample-based (and break-centric) genres — and, natch, absorbing other people’s opinions on the subject. But this remains, ultimately, an intuitive sense of things.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Getting at the stats isn’t any easier, and pursuing them is itself often an ambivalent activity. There is the-breaks.com of course, which, however, tends only to list hip-hop tracks that employ samples (and, in the case of the Amen, only 32 out of what is surely a far greater number). As a hobbyhorse and a relatively small-scale, user-supported endeavor (without the critical mass of a project such as Wikipedia), the-breaks is doomed to incompleteness, and certainly slowness. And with a break like the Amen, which has likely supported far more jungle/d’n’b tracks than hip-hop beats, a site like the breaks is likely to be a poor barometer for overall trends (esp given the proliferation of sample-based tools and styles).

Far as I know, the-breaks has few analogs in the worlds of jungle, drum’n’bass, techno, house, etc. (Though if anybody knows of some useful ones, let me know. I’m sure there are some ambitious, if more informal efforts on various sites and message-boards out there.) The reggae databases seem to outstrip all other genres in their robustness of data and searchability. And there’s the ever-impressive and useful discogs, though there doesn’t appear to be a strong effort to document samples there. (Which would require a different level of archiving than is customary in discographies, but which would bring in some increasingly important metadata.)

But even if taken in such a direction, a site like discogs might be ultimately too limited in purview, restricted as it is to more-or-less ‘official’ releases. I suspect that all of the sites mentioned would fail to take into account not only ‘amateur’ recordings and the vast and vaster world of CD-Rs and mp3s, but dubplates and rly-indie releases too. (In the age of self-publishing and purely digital distribution, what constitutes an ‘official’ release?) Much more music is made than ever can be heard — never mind archived and annotated! Perhaps with a committed enough (and diverse and big enough) community, the collective headz could make strides toward something to give a more confident sense of which samples reign supreme, though we might better spend our time asking why we care in the first place. And yet, even with the participation of producers, collectors, scholars, and enthusiasts of all stripes, such a database would still surely still overlook some of the more subtle or undocumented or ephemeral or secret uses of samples. (One could argue, tho, about statistical significance here, I suppose.)

We can hope and pray for the Superwiki of Musical Metadata®, but even this idealized project runs into significant snags, esp in the realm of ethics. In the current litigious climate where sampling artists are being sued retroactively by the boatload, and court cases are not going their way, the very activity of assembling this sort of knowledge is fraught. Aside from sample-sniffing scum and other sellout species, who wants to be complicit with such reprehensible entities as Bridgeport Music, a large “publishing house” with strong holdings acquisitions in well-sampled catalogs, which has initiated over 800 suits in the last 5 years? (Jay-Z being the latest target.)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Practical and ethical issues aside, let’s return to the main question for the sake of speculation: is the Amen the “most sampled” “break”? As I mentioned above, my intuitive sense is that the Amen break has indeed been employed a staggering number of times — quite disproportionate in relation to most of its breakbeat kin. Even so, I can’t confidently say whether it is or is not the “most sampled” break. And part of my hesitancy here is that I’m aware that there are several other recordings, similarly seminal we might say (blame the patriarchy), which I suspect might vie with the Amen at the top of the heap.

Although I think it’s a stretch to say that the Amen was “foundational” for any genre (e.g., jungle was both emergent and breaky before it adopted the Amen as drumkit, while the Apache, et al., have rolled alongside it all the while), I’d agree that it’s quite difficult to imagine jungle and d’n’b without it.

But as S/FJ said the other day w/r/t Battery Brain, the Amen is but one of several recordings that might claim the distinction of having served as, in Sasha’s words, “the basis for an entire genre.” (And, btw, that Dave Thompkins bass romp he links to is well worth your time, as will be, I’m sure, dude’s forthcoming book on the vocoder, which promises to be on some nextlev, as usual.)

This basis-of-a-genre crew is a constellation of breaks/riddims/recordings that I’ve been giving some thought to for a while now, as I find it a rather fascinating and potentially deeply significant phenomenon (which points us again to the question of why we care, about which, more below). I’m keen to know if I’ve missed any obvious or not so obvious examples, but here’s a short list of some such “formative” breaks (to my ears):

- Battery Brain — which, as Sasha alludes, has played a foundational role in Brazil’s funk movement (though it too has its rivals among bass and electro tracks, especially in latter years with the proliferation and circulation of tamborzao loops)

- Dem Bow — absolutely ubiquitous in reggaeton (which, let’s not forget, was called “dembow” for a spell), as can be heard on the scratching-the-surface mix I made; in a way that one couldn’t for jungle, one might be able to argue that it’s just not reggaeton without the Dem Bow (or, perhaps, that there is no reggaeton without the Dem Bow), though it’s worth noting that for all its primacy, the well-worn drumrollin’ riddim often appears in alternation with other early 90s dancehall staples: e.g., Bam Bam / Murder She Wrote, Drum Song, Poco Man Jam

- Drag Rap — without this odd ode to Dragnet as accompaniment, Nawlins Bounce seemingly would not be what it is; similar to the Dem Bow for PR youth in the 90s, the so-called “Triggerman” beat provided a steady soundtrack for NOLA party chants back in the pre-No Limit/Cash Money days

- Amen — indeed, informative and ubiquitous, but to say “foundational” might too strongly overlook the importance (and frequency) of other breaks — which is also what makes it hard to say that any one break has played this kind of role in hip-hop, esp given that DJs and producers have also put a premium on diversity/obscurity (which is not to deny a core group of well-worn warhorses), but if any one was, it would probably be…

- Funky Drummer — which certainly competes with the best of ’em (many by the same funky drummer, incidentally) for most sampled breakbeat in hip-hop, and has no doubt played a strong role in shaping/affirming hip-hop’s timbral and rhythmic affinities; but as the-breaks.com shows, it is but one of many, many recordings that have been used by hip-hop producers

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

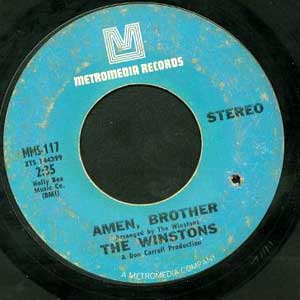

I realize I’ve gone on at some length here without really addressing the crucial question of whether (and why) it matters that one break might have been sampled more than others. That’s too big a can of worms to open at this point, so allow me to close by offering some possible areas of inquiry with the contention that it’s not only important to think about such issues alongside the more straightforward ones about assembling and making sense of data, it’s far more important. Qualitative studies can no doubt be informed and supported by accurate, robust, analyzable data (yo Pace, where you at?), but quantitative methods don’t get us very close, I don’t think, to such issues as, if I may submit a few: pliability of forms, creativity against constraints, public domain activism, supremacy of analog technologies (and/or digital !), the idiosyncratic sound of the band (esp the drums), the inspired performance of the Winston’s drummer, Gregory Coleman (whose recent passing seems conspicuously unregistered among the denizens of the breaks), the resonance of well-worn, remixed recordings in the age of digital reproduction, the aesthetic implications and cultural politics of such practice, and on and on and on and.

These are but a few possibilities. And this whole post is just a big thinkpiece (this whole blog, really). So feel free to add to the list, revise it, question my foundational assumptions, or chop the whole thing up and reassemble at 165 bpm. (Wobbly bassline optional.)

///

ps — Having just finished composing this, a search led me to a somewhat similar discussion (ca. ’93) over at blissblog (undoubtedly, this conversation has been repeated in many corners), including the following SF/J testimonial:

Most hip-hop heads, like me, were unimpressed with jungle for a while PRECISELY because we knew that sample. It turned out that holding “Amen” constant for all artists — almost like a rule in sports — and then requiring them to crack it open and chase a diminishing horizon of returns was the BEAUTY of jungle. But dumb headz just thought “We know that one — come on, dig deeper.”

Dig deeper, indeed.

Cross-posted to riddimmethod

Excellent post. It’s so nice to see someone adding some complexity to this discussion.

When I saw the announcement of Nate Harrison’s documentaries, I was both excited and nervous. Why do we need to confer “foundational” status on any sample or break? Automatically, this privileges the genre(s) where the sample/break in question is most ubiquitous. I would argue that one of the biggest problems with forging a history of a meta-genre like sample-based musics is that automatically certain narratives must be left out for no other reason than ease. There are simply too many stories to consider in the last 25-plus years of popular music making. Once you depart from the Billboard charts, there is no mainstream story, and the historian/critic must make choices (ethical to the core) that could have devastating effects if she is acting alone or in a small group.

Take, for example, the narrative of EDM codified by Simon Reynolds and the contributors to Peter Shapiro’s Modulations. We don’t see much of a discussion of mainstream popular dance music from the same period (Euro-dance, Club MTV, and Italo-disco, to name a few). Suddenly jungle, hard-core and non-booty hip-hop are where it’s at. Anything that doesn’t have arty posturing, or the potential for deleuzian post-modern readings, is too difficult to fit in. Kind of eerie if you ask me.

I could keep going, but I suppose I should save it for my own blog… ;)

I suppose you should, Kariann, tho I appreciate the thoughts here. (But if you’re gonna mention your blog, you could at least provide a link ;)

It’s worth noting that Modulations has sidebars on bass and freestyle and synth-pop, but, yeah, they’re only sidebars. Limited space creates some hard choices, but we definitely need to think hard about where we draw the lines. On a related note, lots of Caribbean and other putatively “world” music — often crucially if not entirely electronic in constitution — also gets left out of various electronic music narratives. Matters of taste do come into play quite heavily, so “uncool” — indeed, “hot hot hot” — music such as soca and merengue don’t hardly get a nod.

I went on quite an “amen” frenzy after we heard dj miles play the winstons’ track at star shoes that night after then conference. my first impression was a strong urge to play it over and over, rewinding 15 seconds and listening again and again. Dave Eggers writes about repeatedly listening to songs until he figures out their *secret*. Even if its not the most sampled ever, I think its fair say that the Amen break is the most addictive, somehow remaining elusive and mysterious despite its simplicity and ubiquity.

What do you know about the copyright history of the song? Wiki says “Neither the drummer, Gregory C. Coleman, nor the copyright owner Richard L. Spencer, the Grammy-award winning composer and performer of the hit “Color Him Father”, has ever received any royalties for the sampling.” Has someone else (a record company, presumably) been collecting royalties or has this songs penetration into the “collective audio unconscious†somehow located into the public domain? Can anyone sample this track without fear of being sued?

I had dream with time elaspsed audio, but it wasn’t high pitched chipmunks (which would logically make the most sense) but some slowed and throwed / chopped and screwed ish.

great post, best ive read. blog on.

el canyonazo

According to Nate Harrison in his documentary (which you should definitely peep if you haven’t yet), the Winstons remained copyright holders and have never sued anyone over the use of the break (to date). That’s pretty amazing, I’ll admit, though the way sample litigation was going for a while (which is to say, chillingly, but not exactly unreasonable in its reach), the copyright owner might have had a hard time proving — esp given the prejudice against drum breaks/beats (i.e., non-pitch elements, or “purely” rhythmic passages) as something for which one could reserve a publishing right (but not a mechanical right, which was always granted) — that a loop of the break (a la NWA or Mantronix) constitutes an infringing use, never mind the sort of radical (if recognizable) re-assemblages for which jungle is known. The “three notes” case changed that, though, at least for the time being (and for the US, of course), ruling than an unauthorized sample of any length was an illegal use.

Harrison argues in the doc that the Amen break has passed into a kind of public domain status as a result, which I would agree with. (He also points out some pretty shady practices whereby breaks-records cats have redistributed it under their own copyright, which is bogus.) Of course, if “people” like Bridgeport ever get their hands on it, watch out, but for now, I think it’s pretty safe to chop and paste.

I agree with you about who gets excluded. Those “world” beats aren’t exactly the most popular subjects of EDM narratives, and when they are included, it is with the utmost suspicion. (I’m thinking of John Hutnyk’s work here.) When I taught my class last summer and dared to include genres from outside the U.K. and the U.S., some of my students were noticeably irritated. (Dude, why is she talking about this when she could be playing Paul Oakenfold?)

Meanwhile, I pleasantly surprised a vocal minority…

Speaking of Amens – check this out. The start of an amazing looking project which features a lot of very useful tidbits of info, and finally gives props to the amen originators:

http://www.subvertcentral.com/forum/viewtopic.php?t=33698

I like, I like – an excellent and appropriate qualitative response to a quanty question. since we’ve batted this around in the past I just thought I’d voice my total agreement that quantitative analysis is only a means, not an end, to interesting intellectual labor – even the driest numbery shit needs to be sheathed in some quali-contextual lube

that said, I’d also add a comment-sidebar noting that quantitative analysis, while relatively helpless to address many of the issues you list, has its own unique spheres of superpower influence that go beyond simple verification and reification –

for one, in my own idiosyncratic, inevitably qualitatively-expressed opinion, statistics have maybe their greatest value not in supporting but in challenging qualitative assumptions, as a kind of check against the kinds of rhetorical excesses that inevitably build up in our qualitative narratives (especially those stories we construct collectively, where groupthink and historically contingent norms can play a hugely distorting role). in stats and other mathy proofs, you don’t prove anything, you disprove alternative hypotheses, which is the right vibe for their use in the humanities, too

equally importantly, well-constructed quantitative surveys can illuminate areas of concern that have previously escaped the qualitative spotlight – which, for all kinds of above-alluded reasons, is often shone on the familiar ‘stars’ of our immediate attention, leaving much of potential interest in the darkness

Thanks for the link, Droid. Sounds like an interesting, promising project. Great to hear that the original engineer is still around and forthcoming. I’m sure it’ll blow his mind to learn about the long life of that break.

And, I hear you, John, esp those last two paragraphs, which remind me of an email exchange we had a while ago wherein you pointed me to some apropos convos, if I may:

Great article. How about “Under me sleng teng” the Casio MT40 riddim which launched a thousand (well 380 according to wikipedia) tracks?

Good point, Paul! Reggae’s riddim system definitely offers another great set of examples of well-worn riffs and rhythms. The reason I don’t include them here is that, for the most part, the subsequent versions and re-uses of popular riddims like Sleng Teng are not based on samples but are “re-licked” by studio musicians. Now, as it happens, Sleng Teng is a bit of an exception in this regard since it’s very distinctive MT40 sounds are fairly crucial to its resonance. I’ve definitely heard many a Sleng Teng sample crop up in reggae, hip-hop, and various UK productions over the years. Definitely an important thread in this whole conversation. Thanks!