As some readers of both this blog and The Wire might have noticed, I’ve started to contribute now and then to their reviews section. As per my usual practice, I’ll be reprinting the reviews here on the blog, once they’ve enjoyed their print run, usually offering something of a “director’s cut” (more words! glorious words!), even though I’m quite grateful for the magic of concision and clarity that editors like Derek can wring out of my prolix prose. My reviews no doubt read sharper in the magazine, but blogs — at least this one — are great places for picking up clippings from the cutting room floor and giving people a little more to read, and comment on.

An edited version of this review was published in the February 2010 issue (#312).

You can preview tracks from the compilation, and place an order, over at Soul Jazz.

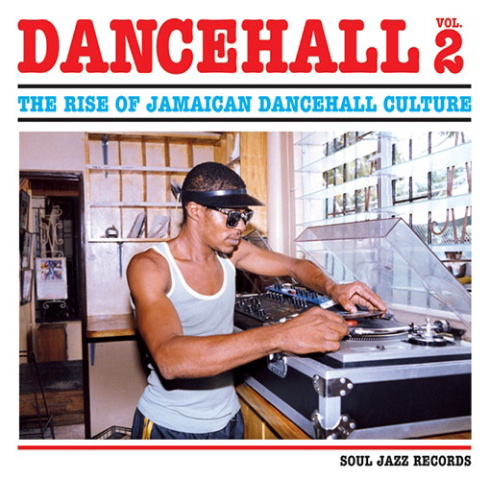

Various Artists

Dancehall: The Rise Of Jamaican Dancehall Culture Part 2

Soul Jazz 2xCD

So rooted in local music venues that it became synonymous with them, dancehall captured Jamaican audiences by staying down-to-earth and up-to-the-time. It remains reggae’s prevailing style even as detractors wonder, in an era of autotuned vocals and fruityloopy beats, if it still merits the name. Some stakeholders, including the compilers of the second double CD in Soul Jazz’s Dancehall series, argue that dancehall has met its demise. Their project is one of reverent exhumation, and though that blurs one line while drawing another, dancehall’s seminal sides can speak to skeptics and boosters both.

Despite the break that dancehall marks — most notably in the ascension of rapping deejays to primary frontmen — the compilation’s tracks bare their roots. Nearly all feature re-licks of classic riddims, including Studio One perennials Rockfort Rock, Heavenless, and Full Up. Small, tight studio groups reanimate well-worn instrumentals, offering spare interpretations–often two-bar, taut but supple grooves–that leave space for deejays to toast and soundmen to dub. Showcasing dancehall’s domination by microphones and mixing boards, the comp includes several longer cuts comprising a few minutes of deejay recitation followed by the producers and engineers taking their turn, flinging horn snips, vocal clips, and renegade snares across the stereo field. Errol Scorcher’s hilarious “Roach in De Corner,” clocking in close to 9 minutes and featuring classic interjections (“Bim! Kill him! Shhh!”), rides a heavy Ansel Collins version of Real Rock which, over its last five minutes, breaks down in every imaginable way and a few others as well. The compilation focuses on major mic-men — like Lone Ranger, Nicodemus, and Yellowman — who draw heavily on humor and critique, revel in local (and lower-class) slang, and rap more melodically than often acknowledged, but it includes the day’s top singers, many of whom, like Johnny Osbourne or Half Pint, navigate dancehall’s spiky topography with a spry delivery.

While these tracks connect dots between roots and dancehall, the compilation redraws an old line by shying away from the synthesized productions that have dominated since the mid-80s. Notable exceptions are Papa San’s deeply digital “Money a Fe Circle” and the Steely & Clevie produced “When” by Tiger — drum machine driven dancehall at its bouncy best. More often one hears subtle touches of digital tricknology, like the syn-drum percussion pioneered by Sly & Robbie, as on Ini Kamoze’s “Trouble You a Trouble Me,” wielding a synth clap like a machine gun. The compilation finally betrays its bias when nodding to latter day dancehall but offering only modern roots throwbacks. Shabba Ranks’s “Respect,” riding a wicked Hot Milk re-lick by Bobby Digital, is almost overbearing in this regard. In their defense, the series aims to cover The Rise of Jamaican Dancehall Culture (though promotional materials make broader claims), but what feels left out, ironically, is a sense of how dancehall has remained rooted in the spaces which branded it, even three decades later, precisely by staying up to date.