Last night at Beat Research the employees of Cambridge-based video game makers Harmonix swarmed the E Room with their friends, their gadgets, and their various musical side projects. They put on quite a show, and to a packed house! Video killed the radio star, but Rock Band might make some rock stars yet.

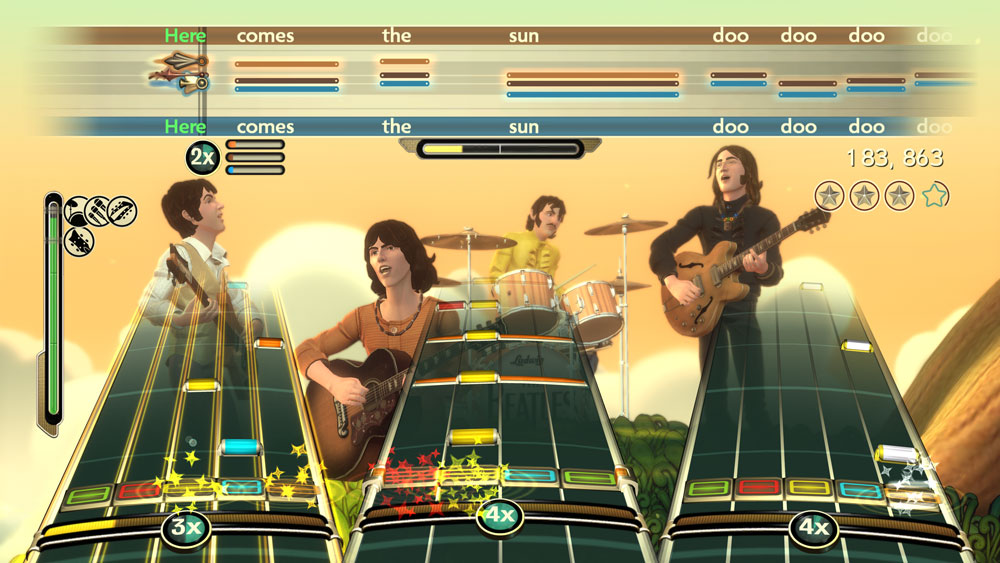

Harmonix is in the news right now as they gear up to release the newest edition of Rock Band. Devoted to the Beatles, the game has been generating a lot anticipation and a lot of commentary. The Fab Four — by which I mean Paul, Ringo, Yoko, and Apple Corp. — are remarkably and, in some cases, notoriously strict controllers of their music and brand. Case in point: their recordings are still unavailable via iTunes. So the fact that they signed on with Harmonix speaks significantly to their belief in the potential of the game — and, it goes without saying, their ability to maintain close control.

This emerges, alongside countless other fascinating bits, in a recent NYT magazine article, in which Harmonix founder and CEO Alex Rigopulos claims no less than to be on the brink — and at the helm — of a new era in THE music industry:

… last month Harmonix announced that it will license software tools and provide training for anyone to create and distribute interactive versions of their own songs on a new Rock Band Network, which will drastically expand the amount and variety of interactive music available. Already the Sub Pop label, which released the first Nirvana album, has said it plans to put parts of its catalog and future releases into game format. The Rock Band Network is so potentially consequential that Harmonix went to great lengths to keep its development secret, including giving it the unofficial in-house code name Rock Band: Nickelback, on the theory that the name of the quintessentially generic modern rock group would be enough to deflect all curiosity. After a polite gesture in the direction of modesty, Rigopulos predicted, “We’re really going to explode this thing to be the new music industry.”

The possibility of opening up the Rock Band platform for all manner of artists and labels (not that they’re offering to do that exactly) is definitely an exciting one, and the release of the Beatles game will no doubt prove a major marketshare expansion for Harmonix. What struck me throughout the article, however, was not so much the implications for (the?) music industry, but rather, the bizarre contradictions that emerged around questions of control (of the Beatles’ “property”) and, simultaneously, an acknowledgment that the Beatles are inherently (and increasingly) a fan-produced phenomenon.

Paul seemed to voice this recognition most clearly when he says that a Beatles edition of Rock Band “reflects where the Beatles are at,” since, as he puts it —

We are halfway between reality and mythology.

I suppose I’d agree with that (and/or this). But this recognition of the Beatles’ mythologization seems pretty ironic alongside the band’s cautious and occasionally litigious actions with regard to “unauthorized” uses of their music. The article describes the deep degrees of tricknological secrecy and protectiveness applied to the project c/o Giles Martin, the audio engineer son of fifth-Beatle and legendary producer George Martin and Harmonix’s point of contact with the Beatles’ master recordings.

Mainly Martin worked in the less-iconic Room 52 down the hall, next to the men’s room. Apple’s preoccupation with security meant that the high-quality audio “stems” he created never left Abbey Road. If the separated parts leaked out, every amateur D.J. would start lacing mixes with unauthorized Beatles samples. Instead, Martin created low-fidelity copies imprinted with static for the Harmonix team to take back to the States — in their carry-on luggage. They were just good enough to work with until the game coding could be brought back to Abbey Road and attached to the actual songs.

I found the references to “amateur D.J.”s and “unauthorized samples” — even though it’s unclear whether these are Martin’s or the author’s words — pretty interesting to read against McCartney’s quote above. In other words, THX 4 THE MYTHOLOGY BUT DONT DO ANYTHING UNAUTHORIZED K? Or, you’re welcome to re-meet the Beatles, but don’t try to re-mix them.

One wonders what would be the harm of “amateur” DJs “lacing” mixes (now there’s a verb) with “unauthorized” Beatles samples. I mean, as “amateur” products such mixes would not circulate in the same market at the Beatles, or any market for that matter. Moreover, however craptastic their new contextualizations, they could never lessen the power of the original songs. And what harm would fantastic remixes be? Could such critically-acclaimed and popularly shared projects as the cease-and-desisted (but only kinda) Grey Album, or DJ BC’s The Beastles, actually degrade or dilute the Beatles brand? Detract from their mythology?

How is one supposed to participate in the Beatles’ mythology anyway — a mythology which, like all myth, can only be collectively produced and maintained — if one needs “authorization”? This paradox brings us to one of the oddest, and perhaps most disturbing and incoherent, quotations in the piece:

McCartney sees the game as “a natural, modern extension” of what the Beatles did in the ’60s, only now people can feel as if “they possess or own the song, that they’ve been in it.”

Only now? You mean that when I bought those CDs and sang-along with friends and family and learned to play your songs on guitar and tried my hand at remixing a few tracks … you mean that all that time I’ve yet to inhabit or possess your songs. Shucks. I guess I’ll have to get the game.

This is all a little maddening for those of us who insist on our rights to work with and riff on public culture — especially public culture we hold dear. (And I do hold the Beatles’ oeuvre quite dear, in case you didn’t know.) Few things could be more public than the Beatles’ repertory, which, to paraphrase John, might be more popular than Bible hymns. In the face of all of this, I have to stand by a bit of insight I came by some years ago: if Michael Jackson can own the Beatles’ music, so can I.

McCartney is either disingenuously hyping this product with a quote like that or, I just don’t know — maybe the author distorted the sentiment somehow. I can’t swallow that Paul actually believes playing Beatles Rock Band is truly the first or only way to “possess” or “own” or “be in” his & his bandmates’ songs. I think we either do all of these things anytime we engage seriously with a song, in the many ways that may happen (listening, singing, playing, tweaking), or we never do, even those of us who write songs.

Musician and writer Ethan Hein, who himself recently posted about Rock Band and inhabiting songs, also seemed a little irked by McCartney’s comment. His retort? “You know what really makes me feel like I possess a song? If you let me remix it.” The last few words of that sentence link to a meditation on sampling which includes a pretty resonant paragraph with regard to the ownership of songs; allow me to quote Ethan at a little length —

When I was an angry, confused teenager, I let myself be convinced that ideas are property, that it’s possible to steal them and thereby harm their owner. I listened to strongly opinionated musicians and critics hold up originality as the main criterion of artistic worth. Then I got out into the world and did a lot of playing and interpreting and composing of my own, and at the end of the day I’ve come to feel that to assert ownership of a song is like trying to assert ownership over a person or an animal or a place. You can have a close relationship with a song, you can be present at its birth and you can give it nurture, but once it grows up, you can’t control it. Why would you want to?

Say word. At that, I’ll leave you with perhaps my favorite Beatles mashup. Good luck removing this from the world! Or figuring out who “owns” it —

Oh, and props to Harmonix and the Beatles. I bet the game is gonna be great. SRSLY!

Your fave Beatles mashup is now my favorite Beatles mashup. Thanks for that, and for recent illuminating commentaries and links on ownership and copyright law. I wonder if you’ve seen this?

That video OWNS!

wayne, while i agree with most of what you post, and though what Paul said may indeed be obnoxious… the question that begs to be asked here is:

why do they “owe” us (the community of DJs and producers/remixers) any of this? if the remaining Beatles don’t want to release the multitracks, that’s entirely their right and not a despicable thing. sure, it would be dope to have those separated parts around, and it’s a bit unnerving in that you can almost HEAR the condescension in Martin’s voice when reading that bit about “amateur DJs”… but again, it’s their music.

why the hyperbolic sense of entitlement regarding their multitracks?

i’m no proponent of arcane copyright laws. i would love to have that material just as much as any other producer, but it doesn’t mean i think it’s absurd that they are trying to protect those sources. it’s their right to continue licensing those recordings as they see fit, even if the “community” doesn’t like it…

Hi, 100dBs. Thx for RTing — and for the comment.

I’m not objecting to the protection of their multitracks per se, though I do think it would be cool if more musicians made their “stems” available, reserving whatever rights they’d like — e.g., BY-SA-NC-whatevs — tho preferably toward the permissive end of the spectrum.

I understand wanting to protect one’s individual tracks, but I also come at this representing hip-hop, where acapellas and instrumentals have long circulated independent of each other and where sample-based culture encourages a desire/search for *more* musical materials to work with (even as it also values the virtuosity of finding the bits in a mix that are malleable). Hip-hop’s sample-based approach — especially in conversation with longstanding antagonists in the legal/industry — engenders a certain sense of contempt for people who try to lock up sounds at the expense of creativity. Maybe it’s a bit like the classic hacker mantra (info=free); not trying to glorify, just sayin.

I recognize that I may be to the (copy)left of plenty people, even those who profess fairly liberal views about the ownership of “intellectual” “property,” but I’m not so sure, actually. When I look at practice — what people are doing — rather than listening to pundits (ahem, like, me?), it seems that people copy like mad and the world is rarely poorer for it. (And when I talk about copying here, I’m not talking about str8-up duplication rackets; I’m talking about creatively using something.)

Do they “owe” us anything? No. Do we have the right to certain things that they decide to publish / make public / publicize / put out there. Yes.

I still have a copy of this on CD, incidentally; perhaps I should return to these “stems” again. I’ll call it an “unauthorized amateur remix.”

One final point of irony: most of the Beatles records are hard-panned between vocals and instrumentals, or certain instruments/voices. So simply panning left or right — or grabbing that part of the waveform — gives access to all sorts of “stems” and instrumentals. That’s one reason hip-hop producers and mashup artists alike have sampled them for so long.

absolutely correct on these factual points, but that’s obvious to any producer.

hard-panning is a godsend for us… i guess what i’m saying is that, if they don’t want to put it out there for everyone in a really easy format, maybe it will be MORE interesting in the long run. i’m not of the mindset that “amateur DJs are stupid” or anything like that, but i also like to see when people put some work in. lifting a sample by taking advantage of hard panning in old dub tracks or stuff from the 60s is a classic technique that is being lost, to a degree. a lot of younger producers hardly know what hard panning even means! as you may have guessed, i also support (for the most part) the hip-hop-centric idea of distributing acapellas and instrumentals, doing blends (waaaay before they were ever called mashups), etc. etc.. but there’s an obvious difference (value-wise, in my opinion of course) between putting out a Beanie Sigel 12″ with the instrumental and acapella on there and putting out the Beatles’ back catalog out as TRUE multitracks. Beanie needs that exposure and those bootleg remixes. the Beatles don’t. could they benefit from that? sure. do they need it? no. hence why you see many mashups that combine one really popular ENDURING artist with one that is “hot right now” or something similar.

i guess part of my argument is that if every really dope musician distributed their classics as garageband-ready files, we would have to wade through tons of bullshit just to find one brilliant rework.

it’s a double-edged sword, as you’re well aware: bring technology to the masses, and kids who could never otherwise afford to do certain things are all of a sudden killing it and able to express their tremendous talent. on the other hand, tons of lazy people are creating more noise that obscures the signal… it’s a jungle out there. for every amazing thing i’ve found on the internet, i’ve found 100 things that i never should have looked at if i wanted to get anything done.

of course, i’m no elitist. people are going to do what they’re going to do, and your argument is essentially that the law should account for that (in an artistic sense). i know exactly where you’re coming from, and i’m glad there are people writing about this. this isn’t a plug, but for example, a while back i did some Aphex Twin mashups. rap/dance/pop music fans were into it for the most part, but i got a ton of hate from a few Aphex fans! why? because they couldn’t believe i had the audacity to “defile” such masterworks with pop music or whatever (someone actually used the word “defile” – wow).

so of course i see your point about allowing fair use. and i do think more works should take advantage of creative commons licensing (we do with Theory Events and Drum Attix recordings). but at the end of the day, i also believe in the rights of artists, especially ones as culturally significant and influential as the Beatles. i know they’re filthy rich. i know they don’t need more money. but they are their recordings… maybe it’s ok if it’s a bit difficult to freak the samples. isn’t pan-separation enough anymore? i’m not sure we need more material served up on a buffet platter right now.

thanks for the nuanced position, 100dBs, and the plugs (always welcome when relevant).

i see that we agree on a great deal. i think maybe we disagree on two things: 1) the rights of artists to limit others’ use of their productions; 2) the trade-off/tension between democratizing production and filtering for quality.

re: #1 – i don’t think that artists should have rights to limit what others can do with their work once published (except, again, to protect against raw commercial exploitation — which is to say, to cash in on it themselves). many will disagree with me on this, and that’s why lots of places (but, notably, not the US) maintain a notion of “moral” rights which grant artists the ability to prevent someone from using their work in a manner they deem inappropriate or from creating a derivative work that departs from their own vision of the original. (i think this gets into interesting grey areas when we’re talking about a hate-group or, say, the republican party using a song that the artist never intended to be used that way; but even then, i tend to favor the first amendment.)

re: #2 – i’d much rather live in a permissive (rather than permission) culture where everyone is making stuff and where the tricky part is sorting for quality or affinity than a world where a select few are producing and i’m still tasked with sorting for what i like. (there’s always already too much out there, if you’re really digging.) i think that with tagging and socialnetworking and social media, etc., the job of filtering is becoming easier and better despite the explosion in the number of things available to us. i far prefer a situation in which we are all creators, riffing on the same stuff (or local/idiosyncratic variations thereof) than one where the options — and the level of creativity — are more limited.

ok, points taken. i can certainly respect those arguments. the grey areas are very interesting.

btw, another interesting but totally separate point is this: let’s think about 1989 vs. 2009. if every kid who had dreams of becoming some sort of rock star picked up a real guitar instead of Rock Band or Guitar Hero… MAYBE we’d have some more/better musicians around. sure, 90% of the kids who pick up a real instrument don’t ever get anywhere with it, but i really do believe that back in the day those wild fantasies really drove some people to new creative heights. i know because i was one of those wide-eyed kids, when these interactive video games weren’t around. these games are so corny.

and i’m not hesitant to claim that in some way, as much as the good things it’s brought us, the digital era has shepherded young minds into believing the only way forward is by RE-doing something, or doing it virtually. with a computer. or with a game.

to a degree, we’re losing our ability to create (and maybe even recognize) music at a roots level. not a good look.

i <3 computers as much as the next guy, but i don’t think people should forget about the real thing. whether self-taught or not, the knowledge gained from learning drums, guitar, bass, piano, or any physical instrument is paramount to producing original works of music. and if we have any hope of enjoying “original” (whatever that means) music in the future, we should be encouraging kids to play real instruments early on.

I can respect your arguments too, but I have to disagree once again — this time with regard to questions of originality and, as a corollary, cultural vibrancy and sustainability.

Obviously it’s still too early to tell what the implications will be for a generation (or more) raised not on traditional/acoustic musical instruments but also (or even primarily/exclusively) on electronic and virtual instruments (and, depending how you feel about it, even on “non”-instruments like the Rock Band controllers; I think they’re instruments too, however, for the record).

But color me optimistic. I’ve seen what a generation (or two) raised on turntables have done, and I couldn’t be more pleased and stimulated by the results. From my perspective, there’s not necessarily any kind of hard line we can draw between the virtues of “real”/trad physical instruments and their electronic or virtual counterparts (aside from that of electricity, of course, which is sort of immaterial here, unless we fear a total loss of it, which may be a possibility, in which case, back to the acoustic drawing board).

Even with regard to the question of doing something vs. RE-doing something, I’m skeptical that there’s a hard line to be drawn. I’m a firm believer that all “original” creation — in the realm of culture & ideas — is actually always (already) a synthesis of other people’s ideas. I’m with Jonathan Lethem, John Donne, et al., in acknowledging/arguing that culture (& literature, etc.) “has been in a plundered, fragmentary state for a long time” and, if we must get metaphysical about it, that “all mankind is of one author, and is one volume.”

This excerpt seems particularly germane to our discussion:

dope excerpt.

i don’t know what the future holds, obviously. for the record, i most certainly count the turntables as an instrument. i can’t say i feel the same way about video game controllers, unfortunately (unless some n3rd programs some crazy compatible sequencer that supports custom sounds and processes that they work with). what i’m talking about revolves more around physical interactions with instruments vs. ONLY using sequencers and computers. i strongly believe in that raw interaction being necessary as a learning process. of course, i use sequencers as well.

we may agree more than either of us think – basically what i’m saying is that everything should be explored, but let’s not forget what got us here because it’s the foundation. i *think* what you’re saying is that everything should be explored, and everything has merit because it’s all pushing things forward anyway.

maybe they’re two sides to the same coin.

regardless… keep writing!

Great stuff, as always. (I’ve just posted the link on the NYT author’s FB wall.) Thought I’d mention that it looks like they *are* pretty much planning to “open up the Rock Band platform for all manner of artists and labels” — though of course some restrictions are bound to emerge. See http://g4tv.com/thefeed/blog/post/697536/Who-Ya-Gonna-Call-To-Help-Get-Your-Music-In-Rock-Band-These-Guys.html, http://www.rhythmauthors.com, http://creators.rockband.com. This last link does make reference to “approved tracks” — presumably copyright will be an issue in the approval process (unlikely that a mash-up artist could get a track approved, I suspect). But based on what I’ve heard, it sounds like ensuring that the coding is musically accurate and makes for satisfying gameplay will really be the key thing.

Sounds promising, Kiri! I hope it proves true that the platform truly is opened up to the participation of anyone willing to put in the work to code their own songs, cut a deal, cultivate demand/awareness, etc. I guess I just worry that it might turn out to be a situation more like the Apple app platform, which is in some ways theoretically “open” to anyone but has proven less consistent in practice. But I have faith in the Harmonix ppl, so far.

I bet it’d be pretty fun, and challenging, to play one’s way through “Let It Be Me” ;)

ps — nice job (again) navigating the valley of magazine journalism! way to represent for ethno–

Thanks W! I share your cautious optimism. btw, for any blog readers who didn’t read the whole NYT article, it’s worth noting the author’s own position on this stuff: “The Beatles’ music may be best served by the philosophy of its own era, when artists constructed and controlled packages of music designed to be experienced in a precise way. But surely the promise of interactive music is that listeners — participants — will be able to add their own personalities to their favorite songs, adjusting and improvising on themes created by the musicians. If interactive music is to truly evolve, it may require more adventurous artists willing to set their songs free and embrace the consequences.”

Moreover, esp for 100dBs, I also want to point to something from the end of the article, where McCartney is talking about the potential effect of a game like Rock Band on the formation of actual rock bands. After we’re told that McCartney “can’t play his own game,” we’re also informed that “he suspects that if it had been around when he was a kid, he would have liked it.” The article continues:

Me too.

1st – I’m still partial to Danger Mouse’s “Moment of Clarity” as a mashy use of Beatles’ work.

2nd – I hadn’t realized that the Pau Gasol had a former life as a Paul.

i know this isnt a very mature position, but in the immortal words of RZA [or was it Nas? Or maybe MF Doom? ne’ermind, maybe it doesnt matter] :: “No matter how hard you try, you can’t stop me now … [because] I dropped a half a G on a rented SP 1200 Sampler, and a Yamaha Four-Track”

i like that McCartney quote. i hope he’s right.

Yah, Wayne. My favorite quote is yours: “I have to stand by a bit of insight I came by some years ago: if Michael Jackson can own the Beatles’ music, so can I.”

After my own long-term imbibing of the romantic artist figure in society, I was more than a little weirded out to hear that one “artist” could exclude another from the ownership and benefits of the latter’s creation–it seemed to contradict that other romantic creative logic. That quote just encapsulates the fact that in our era too much ides of the products of creativity are intertwined with the background logic of $. That Might–I mean, bank accounts–make Right. I mean, do I really need to feed Paul McArtney’s kitty anymore after my misspent youth buying loads of vinyl from him? And sure, if Bob Dylan came to me hat in hand, I’d give him five of my last ten bucks, but does any multi-millionaire artist (much less corporate flack) really need my minimum wage earnings at this point in their back account–I mean, career?

100dBs points are righteous and well-made, but ultimately they just point to the fact that McSilly Love Songs’ claims to creative property rights is based again on money. I’m still of the mind that property really IS theft. And claims to “protecting” creative work just begs the guerilla artist to come out of the jungle and liberate the code from the power of money and the money of power. Just because you are supposedly the first to see or hear or sing a pond or plot of land or that precious song, doesn’t mean you have the right to fence it off with whatever combination of wood or metal or guns or Blackwater or mystifying laws and exclude everyone else. Okay, enough of my chides and cliches for now. But it is highly doubtful even that you really ARE the first, by the way to spot that sweet site (and I still prefer My Sweet Lord to He’s So Fine, and the Beastie Boys use of James Newton’s flute riff to James Newton’s own).

All this reminds me of an online spoof from a few years back where Metallica was supposedly litigating/claiming to own the rights to the Em to F chord progression. (And that reminds me of my composer friend who “wrote” a piece called “Bridges” that strung together just the bridges from Metallica tracks).

Liked the pic of your kid multi-tasking. Good job!

Following up on Kiri’s comments above, it seems the Harmonix people are really serious about opening up the platform to anyone willing to put in the work. Peter Kirn over at Create Digital Music has an in-depth post and interview with the Harmonix folk about it:

http://createdigitalmusic.com/2009/08/27/inside-the-rock-band-network-as-harmonix-gives-interactive-music-its-game-changer/

*Waaaaay* too late to this discussion, sorry.

Just some points:

1. What exactly is a “real” instrument? Whatever happens to already have been invented/widely-recognized before you were born? I say this because there have been cases in the past where *new* instruments weren’t regarded as “real” instruments. (The entire Saxaphone fanily of instruments, if I recall correctly.)

2. How about the Mellotron? The Electric guitar? (Hell, without all the “gadgetry”, solid-body electric guitars sound like crap.) So the argument that anything is being “lost” when technology is added to the musical palette is also pretty specious.

3. Read up on the history of copyright. The entire reason for granting it at all, was to incentivise creativity, and — this is really important to remember — the monopoly privilege of copyright was *always* intended to expire, thus freeing up cultural “product” for future creativity.

The multinational corporate media megaliths have been using front-groups like the RIAA to keep buying themselves longer and longer copyright terms, and attempting to get government to suppress potentially disruptive technologies — Hell, Jack Valenti (okay, so he was from the MPAA, but basically the same deal) actually compared the “consumer” VCR to the Boston Strangler. In terms of a vibrant public domain, I, for one, genuinely believe that artists DO *ow* the rest of us, for the privilege of having monopoly privileges like copyright given them AT ALL. One of the biggest ways they can pay that debt back, is by not breaking THEIR side of the “copyright bargain” when public domain time comes.