“Hipster hedonism takes many forms,” wrote Ned Polsky in reply to Norman Mailer’s hipster manifesto of 1957. “Some hipster groups,” Polsky continued, “have everything to do with motorcycles, whereas others have nothing to do with them.”

Similarly, but more in the abstract, in his genealogy of the hipster, “Hip and the Long Front of Color” (1989), Andrew Ross notes that “Hip is a mobile taste formation that closely registers shifts in respect/disrespect toward popular taste.”

Ingrid Monson provides a more specific historical view of these various shifts in hipster style in her 1995 essay, “The Problem with White Hipness,” while attempting to find some unifying themes across time&space:

The idea of hipness and African American music as cultural critique has, of course, detached itself over the last fifty years from the particular historical context of bebop, circulated internationally; it has inspired several generations of white liberal youth to adopt both the stylistic markers of hipness, which have shifted in response to changes in African American musical and sartorial style, and the socially conscious attitude that hipness has been presumed to signify.

Each in their own way, and all together, Polsky, Ross, & Monson thus help us to think through the contemporary “problem” (or problematique, as ebog would have it) whereby the ontology of the so-called “hipster” seems to have had its connotations loosed from Mailer’s sense of the term — that is, an existentialist rebel attuned to the Negro’s “Messianic mission,” as contemporary critic Jean Malaquais sniped. At this point, at least for some, the hipster simply mediates novelty. From such a perspective, there’s nothing much wrong, beyond a certain superficiality, with being a “hipster” — and I appreciate the critique that the term itself has become an overused stereotype that may obscure far more than it reveals. (Srsly, for all the folk I know who might fit facile descriptions of hipsterism, I can’t say that I would call any of them a “hipster.” Stylee, sure. Hipster, no.)

Indeed, some “dirty pigeons” (thx, ebog) so clearly reject any significations of negrophilia and embrace cultural notions of whiteness to such an extent that poptimistic music critics feel a need to pull their card. Dirty pigeons look even dirtier when white, it seems.

It is deeply interesting to me that so many commenters on my earlier post seem to feel that hipster has lost its race-y meaning. Clearly the whiter-than-white indie rock hipster formation is part of what gives us this sense of a “deracinated” hipster. But Sasha’s provocative piece on “musical miscegenation” (or a certain lack thereof) reminds us of the dialogic relationship between the hipsters who, on the one hand, embrace the signs of blackness in a way that would seem rather consistent with hipsters of the past and those who, on the other, seem to do the exact opposite, to retreat into whiteness, as I’ve called it in the past (& Sasha also employs the term retreat in his critique, notably).

If we see Sasha’s critique of lily-white indie rock as articulating the two sides of the hipster coin, diverging manners of engaging with (or retreating into) racial stereotypes, then we see the way that even that form of hip which seems to reject the symbols of African-American culture is still, in its own twisted ways, bound up with the romantic, raci(ali)st caricature of black masculinity and sexuality that so seduced Norman Mailer into thinking that middle-class whites using the right slang and seeking “the good orgasm” were existential rebels a half-century ago. Rock’n’roll, right, SF/J?

Against all of this hairsplitting, Mailer’s essay remains illuminating. It’s quite amazing how much some of its sentiments still resound with contemporary hipster discourse, even if, as many commenters here have protested, being a hipster today seems, in many cases, to have very little to do with a “fascination with / appropriation of” black culture. But as far as I’m concerned — that is, in my attempt to clear my good name understand the circulation of nu-whirled music — those issues of fascination and appropriation are still very much in the foreground. As is blackness (as a lens into an engagement with the exotic). And the way that I’m trying to articulate that side of the hipster coin is to pose a question about, as I’m currently calling it, “the postcolonial hipster” and in particular the resonance of what we might conceive as “global ghettotech.”

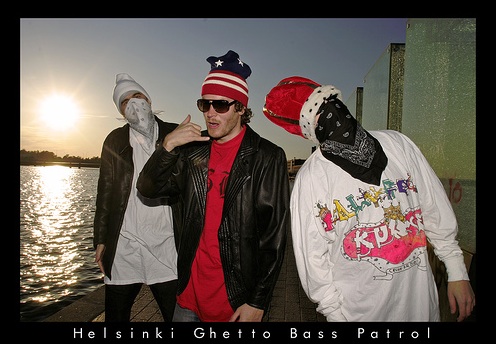

the face of ghettotech (RIP)

A quick search on MySpace returns 42 pages worth of artists or groups identifying as (at least one third!) “ghettotech.” And while the majority of those drop-down menu picks may be simply cheeky or whimsical, there are certainly a good number among them that attempt to wave the banner of ghettotech in some earnestness. (Contrary to popular discourse about hipsters, I think that “ironic distance” is actually kinda overhyped as a mode of reception.) Even if somekinda earnest, we have to ask, what the hell does ghettotech mean to all these people? Is it the same thing it meant to Disco D, the popularizer of the term (according to this primer)? Is it the same thing it means in Detroit or Chitown or Bmore or elsewhere where the term is less likely to be used than, say, the far less ghettotastic, “club music” or “dance music” or “booty music”? I doubt it.

Although my own coinage, “global ghettotech” as a term seems to identify a certain sphere of circulation and a certain (in this case, actually ironic) celebration of the ghetto therein. The irony in the celebration is not a distanced form of appreciation, but a product of the glaring (material) contradictions between those who are celebrating and those who are celebrated.

In a timely, reflexive reflection on the rise and fall of kuduro (at least in the hype machine), Guillaume comes right out and talks about the “hipster blogosphere” as the site for these exchanges, these representations of “hard ass” music. (He also calls himself a “white nerd,” which is an important part of all of this, no doubt. And there’s no way I can duck that label.) It is telling that a commenter at the low-bee forum Guillaume points to, asks of kuduro: “could this possibly be the next world bass bashment after baile?” And that sort of says it right there, or at least draws the connections quite clearly. Moreover, a lot of the discourse around kuduro on that forum marks the search for “NEW SOUNDS” and “staying ahead of the curve” as crucial to hipness in a constantly differentiating economy (of cool, of hot, of sounds and ideas), hence creating new niches for exchange value, as Nabeel points out. Returning to Ross, we find some resonance in the following characterization: “Hip is the site of a chain reaction of taste, generating minute distinctions which negate and transcend each other at an intuitive rate of fission that is virtually impossible to record.” In this sense we certainly see how the hipster mediates (and seeks out) novelty. But the novelty here is, I contend, not simply about newness. It’s about black newness (or is it new blackness?) — coded, often enough these days, as bass.

So I wonder whether the ghettobassosphere is not in some sense feeling the same as Sasha: let’s leave behind (or chant down) whiteness and all it represents, let’s embrace bass, space, and syncopation and all the things we could be if middle-class white women weren’t our moms (to paraphrase Charles Mingus).

This sort of critical move, which can no doubt be read as progressive in certain respects, also gets us into some tricky turf, at least vis-a-vis the historical hipster’s problem with primitivism. As Monson contends,

Whether conceived as an absence of morality or of bourgeois pretensions, this [hipster] view of blackness [as transgressive], paradoxically, buys into the historical legacy of primitivism and its concomitant exoticism of the “Other.”

Sasha’s conclusion then, a winking reference to the etymology of rock’n’roll and the “risk” that came with it, brings us right back to what Monson calls, in reference to Mailer’s celebratory tract of 1957, “the bald equation of the primitive with sex and sex with the music and body of the black male.” And though I’m not accusing Sasha of perpetuating these stereotypes too blatantly (and indeed, I think we should go easy on Sasha and applaud him for painting in bold, broad strokes), there’s no avoiding the resonance, the lurking essentialism, no matter how explicitly we may decry or attempt to avoid it.

This relationship between the primitive, blackness, and desire gets rather directly to what seems like a major part of the contemporary problematique of white hipness: the internet permits new “engagements” with the “Other” that are so thoroughly mediated (by discourse, by distance, by comcast) that the sense of “risk” which once animated hipsters heading up to Harlem has become really quite virtual, and hence, hardly constitutes a risk, or transgression, at all.

Global ghettotech projects old loci of authenticity outward: foreign black is the new black. And in this sense the lens through which we hear something like kuduro emerges inevitably from the cultural / economic logic that makes African-American music global, as well as, I suspect (unfortunately), the (post/neo)colonialist logic that carries forward some rather old, if perhaps not outmoded, modes of reception — the ways we hear and make sense of such new, whirled music as funk carioca, kuduro, and the next flavor of the month.

Sure, this is about (the insidious distinctions of) connoisseurship and perhaps there is no getting past that (indeed, expressing a taste for Bourdieu itself stands as a form of distinction within an academic economy of ideas and status), but I really would like to think that what I am doing here on this blog, even when I’m boosting an Argentinian mashapero or an African-American DJ, is much more than engaging with the “hipster” economy — that somehow my own (hopefully explicit and reflexive) exercise of taste on this blog, not to mention as a DJ or professor, has more to do with calling attention to critical blindspots and ways of reading (or not reading) contemporary culture than with a kind of unreflective circulation of the new (black) that largely serves to boost my own status. Call me naive, but don’t call me a hipster.

Getting down to the nitty gritty, this is about class (as Carl Wilson notes w/r/t Sasha’s piece), and hence race, and — crucially — about the digital divides of the internet: the paradox of an unprecedented degree of access to the sort of exotic cultural symbols (from baile pics to grainy youtube vids) that some “hipsters” employ as cultural capital, coexisting with an actual, racialized, class-based process of gentrification in which the very objects of affection / fascination / appropriation are being forced out of the same local spaces that now provide wifi connections for hipsters to do some DLing on the DL. As I wrote in a comment to my hipster post:

The coexistence of this celebration and embrace of difference against a social reality in which, for all the signifiers of cosmopolitanism around us (esp in, say, Brooklyn, or London), the forward march of gentrification continues apace, makes for a vexing paradox: in other words, our post-colonial neighbors are cool enough to download at a distance, but we don’t really want to live together (or do other things together, as Sasha would have it).

— or as Ross concludes: “Hip is the first on the block to know what’s going on, but it wouldn’t be seen dead at the block party.”

To close (for now), I have to admit that even if the idea of “race” is (perhaps) receding in importance for newer generations, or if hip today signifies yet some recognition of “the far from ideal conditions and circumstances under which racial integration [is still] beginning to feel its uncharted way” (to revise Ross), given the enduringly racialized lines of class inequality in the US (= the other side of the white privilege coin) — never mind the way things look when we extrapolate from the “West” to the “Global South” — I find that Ned Polsky’s bracing conclusion, responding to Mailer, remains rather relevant for a cultural moment that puts 50 Cent on a pedestal / virtual auction block (whether he gets money or not in the transaction is, I’d wager, fairly inconsequential):

Even in the world of the hipster the Negro remains essentially what Ralph Ellison called him — an invisible man. The white Negro accepts the real Negro not as a human being in his totality, but as the bringer of a highly specified and restricted “cultural dowry,” to use Mailer’s phrase. In so doing he creates an inverted form of keeping the nigger in his place.

“Think I’m just too white and nerdy”:

Weird Al Yankovic; “White & Nerdy” on YouTube

The anthem!

I’m curious about one thing – pretty much everyone who posts on this blog is an academic or wannabe academic in some field of the humanities or social science (as far as I can tell). Since this is my only major means of engaging with this music (besides my own head, monologues to my disinterested rockist friends and my now-defunct radio show), I wonder: what is the rest of the “global ghettotech hipster” community like? Are they as reflexive and self-engaging? Or are they just a bunch of “listen to this cool thing I heard” wiggers, buying into what they think is “the lifestyle” completely?

Are we much, much cooler then them? Do we already know that the next kuduro is obviously coupe decale? Are we better at pretending to be disinterested in trendy new genres? Do they all wear streetwear and crewcuts instead of indie hair and kraftwerk t-shirts?

I’m not exactly sure about your generalizations w/r/t to the academic aspirations of this blog’s readership, Birdseed. I’d like to hope that it’s broader than that, and I really do strive to keep the language here engaging for a wider audience than the academy (if maybe not so much on posts like this one). I do think it’s fair to say that people come here expecting smart words about music.

I kind of suspect “the rest” of the global ghettotech heads are not gonna comment here, if they find this or bother reading through it. The post could easily be seen as too couched in esoteric language, or too close for comfort, or both. I can imagine plenty of TLDR reactions.

One thing is clear about the commenters here though: they are almost entirely male. (Big up, Ripley!) Not sure what to say about that, except that maybe it gets at the enduring gender politics of music geekery. Wish it were different. Makes me wonder if I write in a masculinist mode. Blame the patriarchy —

Just a footnote: Radioclit, who have issued “Ghetto Pop” podcasts showcasing both juke and kuduro (my primary examples in the paper I’m giving this weekend), earlier this month offered up a mix focusing on none other than “coupe decale.” Quite the cosmo-ghetto constellation. Good call, Birdseed. (And Boima!)

“the forward march of gentrification continues apace, makes for a vexing paradox: in other words, our post-colonial neighbors are cool enough to download at a distance, but we don’t really want to live together (or do other things together, as Sasha would have it).”

I think the situation is much more complicated than this. It seems like some folks are suggesting that if a white hipster stays in white suburbs he/she is not cool, and if he/she moves into an African-American neighborhood he/she is a gentrifier. A person is damned either way (says this suburbanite). Plus this line of discussion is too simplistic in that it ignores Hispanics and other ethnic groups, and ignores class, which you hint at elsewhere. Middle class African-American DC residents have moved over the last 20 years to certain Maryland suburbs, while working class and poor African American residents have moved to other Maryland burbs. Plus, you would really need to talk about the legacy of Jim Crow segregation on housing and education and the economy and crime and drugs to really get into who lives where and why, and who is willing to go where and why. Perhaps some post-colonial neighbors fit the stereotype you talk about but not all. Also some of this reminds me of that LCD Soundsystem song “Losing My Edge,” about trying to invoke coolness. I am waiting for someone to say, “Ha, I not only listen to ghettotech, I have been doing so in the South Bronx for 30 years where I was the first white person on the block.”

You have at least one college dropout reader..

Dagens Nyheter, the biggest swedish “serious” newspaper, had a short interview today with the people behind a (rather boring) hip-hop/funk/dance club called Raw Fusion. I just have to translate a quote for y’all.

(They’re talking about the club experience in Stockhoolm at the moment. Mad Mats:) “The Music in Stockholm has become whiter and less soulful. At the electro house clubs around Stureplan [upper-class counter-ghetto clubland] today there’s just surface, no homely vibes. People have a lot more money and when you’ve got a lot to chose between you don’t dig as deep. In the nineties everyone was a wigger but now everyone wants to be white. But I guess that’ll turn around when the economy goes down.”

So – is hipsterism a particualrly strong recession phenomenon?

I wanna comment to big you up on this topic. i think it’s important and It’s got me mulling over all kinds of things. As for my 2 cents it’s gonna be tough for me to add. You may have hit the nail on the head with “too close for comfort” for some other DJ/Ghettotech producers.

Playboy’s music editor picks up on the racial fetishism in Frere-Jones’ piece and slams him for it.

http://www.playboy.com/blog/2007/10/paint-it-black-1.html

You raise some trenchant points here, Curm. And you’re definitely right that this is much more complicated than either I or Sasha suggest in our black/white broad strokes. On the one hand, though I think the point about leaving out people who don’t fit into the US’s binary racial codes is a good one, I think it’s also important to realize that such folk are also often interpellated into one group or the other (e.g., latinos become racialized as black; east Asians as whites, etc.).

As for the question of gentrification, I admit that we should approach it with more nuance than I might imply here. Something like the Neighbors Project offers an interesting, optimistic outlook on how to approach gentrification while considering all the complexities it carries with it. I would certainly agree that an “us/them” perspective on gentrification is not a productive way to think about it, and that, as the NP people say, “diverse cities with a healthy grassroots culture, rooted in public streets and institutions,” would be “the preferred place to live for Americans of every kind.”

My only hang-up with this is that in some sense there’s an idea of economic diversity built into this which strikes me as a bad compromise. No doubt, poor neighborhoods would be “enriched” by having wealthier residents move in, and mixed income residential areas seem preferable to the pattern in which the working-class is simply pushed out of their former enclaves. (I’ve seen my own hometown, Cambridge MA, change in some sad ways over the last 10 years, as lots of working- and middle-class families have been “forced” by economic incentives to move out to cheaper suburbs while yuppies move in; this process has really destroyed what used to be cohesive but diverse neighborhoods.) My problem with the idea of upholding the benefits of “economic diversity,” however, is that it sounds like a capitulation to the status quo. While we can imagine all kinds of upsides to, say, “cultural” diversity and appreciating cultural difference, it’s a lot harder to justify why some people should be poorer than others. (Of course, as a “commie curmudgeon,” I’m sure you agree with me on that count.)

I am not justifying that some people should be poorer than others, and I do not think curmudgeon me from the DC area agrees entirely with “Commie Curmudgeon” from Queens either. But I understand your points about the dangers to certain cohesive communities when newcomers move in. Now if I could only remember the name of the author who I heard on a local public radio talk show who wrote a book about what she saw as a African-American female professor moving into an African-American working class neighborhood. So, dealing with the whole issue of who’s poor and why and what can and should be done to change that is a much bigger and more complicated issue than just discussing gentrification ins and outs or whether indie-rock hipsters are less multicultural (and more upper class) in 2007 than bohos were in 1981 (or feel more superior to middle class others who like mainstream pop music than similar bohos did to mainstream pop music lovers in 1981).

Oops. Certainly didn’t mean to conflate curmudgeons!

I’ll note, though, that anecdotes about middle/upper-class African-Americans hardly undermines a critique of the enduring racialized class structures in US society. When we look at big picture stats on health and poverty, for instance, it’s pretty clear that for all the poor whites or rich blacks in this country, there remain deep racial divides around access to health care, etc. You’re definitely right that it’s more complicated than hipster taste, but the modes of distinction in hipster forms of consumption / representation would seem rather structurally related to these larger issues of race and class. Just sayin.

One thing is clear about the commenters here though: they are almost entirely male. (Big up, Ripley!) Not sure what to say about that

interesting to see that mentioned.

it has occured to me that hipness might in part be made of carnivalesque attempts at articulating the space between masculinities and patriarchy.

maleness and patriarchy aren’t the same thing, but i think culturally they are supposed to be interchangeable.

i think maybe that hipness is in part a response to the cognative dissonance that creates.

and it’s not just about appropriating signafyers of blackness, or of adopting a white-ID’d verson of ‘black cool’.

punk appropriated the signafyers of queer street kids, for example.

i dunno. i don’t have a point, just thoughts stimulated by yr post.

as always, thanks for putting it out there.

clearly both black and white hipsters of both races (and sexes) agree that the objectification of women is cool. it is obvious just looking at the way http://fluokids.blogspot.com/ and other powerful music blogs in the hype machine pair photos of sexualized and overstyled women with music and remixes almost exclusively made or “discovered” by dudes. and it takes two to miscegenate and both men and women are guilty for getting to this point where dudes blog and ladies exhibit their approval by waving gold chains on the dancefloor.

i think that part of the lack of participation be women in these discussions esp. in the blogosphere has a lot to do with pressure (self-inflicted and imposed) to participate in the performance of these emerging cultural forms. the women i know at least tend to take a more holistic approach of these global movements and try to stay informed not just of the music, but of fashion, dance, etc that are more inherent abroad (or even domestic…). non-musical elements are more likely to be neglected by the “white nerds.” i remember back when i was first interested in kuduro that i wanted to know more about the dance and aesthetic of the genre but i could not find a sufficient intermediary. the youtubosphere does allow for hipsters and participants to keep up with the pace of what’s going on, but its hard to agree on an evolving idea of authenticity if hipsters consistently fail to adopt the same things that its always been easier for women and men of color to assimilate–fashion and dance. i hear a lot of crank dat remixes by white nerd dudes and the only people i know learning the dances are men of color and women…

i feel like a lot of the blog patriarchy does fear/glorify black masculinity and sexuality AND femininity and sexuality esp. black/latina femininity and sexuality. for a woman of color like myself, its a particularly difficult position between performing cool and talking about it. i have pretty much anesthesized myself from having to negotiate and ideal “blend” of saying and doing by this point. i was dangerously close to not throwing my two cents in here, both out of fear of not being academic and buying into a kind of “either you’re with m.i.a./uffie/amanda blank/santogold or fall back” mentality.*

there is also an issue of content in “new whirled” music as a product of or vis a vis older ghettotech genres. i was talking to my best friend last night and we discussed about how of the twenty words in portuguese i know, about ten of them we know are different words for punany based on how many times we have listened and danced to several different versions of tchutchuca. it has been a dangerous proposition to have ghettotech as the new primary engagement between local hipsters and “other” “foreign” “exotic” subcultures. cause my friends and i have been listening to dancing to “ass and titties” for years (r.i.p. disco d) and its become harder and harder for me to decipher in different circles of cultural commentary what’s ok/ironic/safe-outlet-for-working-out and-deep-seeded-racial-and-gender-role-play what crosses the line into totally aggressive machismo/heterocentrism. scary stuff! i don’t want these fears in common with other ladies like me globally or around the way just now trying to find the language to talk about some of this stuff. w, thanks for opening up the discussion.

*totally with btw, but i wanna save that discussion for later maybe?

alexis, thanks SO much for adding your 2 cents here (or was it 4?). i think you raise some important points here, and i appreciate you bringing them — and your personal perspective — into this discussion. the last thing i want this blog to be is hostile to non-academic or non-male viewpoints. that’s the main reason i blog: to communicate beyond the walls of (male-dominated) academia, much as my own discourse is inseparable from all o that.

one thing tho, real quick — just to push at the lines we draw a lil bit: it’s worth noting that there were plenty of “white nerds,” men included, doing their best to “crank that” over at MIT not long ago —

http://thephoenix.com/article_ektid49121.aspx

Totally agree, I think the entire issue is interesting and I do like to see it raised.

It hits at one of our most basic dilemmas I think – we deal with cultural content that’s (de facto, not literally) battling race and class oppression, while often actively participating in patriarchal oppression or (less importantly, I guess) heteronormative oppression. What should our response be – try to behave “socially responsible” and filter out morally objectionable content, or let everything pass because we shouldn’t be the judges?

All of us here, I think, have more or less chosen the second path with various justifications. (Mine involve participation theory.) But it’s nowhere near a clear cut issue and Thatchell is totally justified in what he says in some respects. I could also add:

We’re not really just impartial observers (as this blog has previously discussed). Even by “just letting through” certain content we’re actively making a choice in support of that cultural system. No matter how “ironic” our singing ass-n-titties is it nevertheless to a certain extent endorses the world of DJ assault, which is a very, very nasty world indeed. It is his choice to make some of the most misogynist music in history (litsen to “Bustos Brothers” or “Hoes Be Trickin'”) but it is our choice too to play it, to listen to it, to pass it on to others.

What should our response be – try to behave “socially responsible†and filter out morally objectionable content, or let everything pass because we shouldn’t be the judges?

maybe there is a third path.

using the ‘objectionable content’ to transgress it’s own normativity through things like juxtaposition, recontextualization, introducing other content/voices, etc. etc.

queering up the mix so that it’s moving beyond mere ironic agreement (or censoring).

Interesting proposal, Dominic. Reminds me a bit of what Kingdom is up to in Brooklyn —

http://www.myspace.com/kkingdomm

heh, i ment ‘queering’ in a broader sense than just homosexualizing.

i think maybe you got what i ment (there is more than that going on with Kingdom), but i feel i ought to clarify because this is public.

and thanks for the link, that’s great.

do you know of Johnny Dangerous, VIP, Sgt. Sass, et all?

yes dom, i certainly didn’t mean to imply too “literal” a reading of queer, but ezra’s lumberthug aesthetic quickly popped to mind — and indeed, what kingdom is up to is definitely bigger than that.

not familiar with these other refs you bring in. care to enlighten with some linkthink? (too busy to google this morning, but enjoying the continued conversation, including lev’s comment here.)

Hey Wayne, I haven’t been too on top of your blog, so smack me (virtually) if this has come up before, but don’t you think that there’s still a degree of irony in the way that people are looking at “global ghettotech” (I’ma run with that meem, thanks for it!)? I mean a lot of the baile funk stuff is derived from some pretty declassé Miami stuff that, at least here in the NYC area as a youngster, was not even black music so much (which would give it wigger cred) but more associated with Italian-American bridge and tunnel types (which can only get cred 20 years later and filtered through Brazil). And for kuduro, too, they’re all popping and locking and doing the worm and whatever, which is pretty ripe for tongue-in-cheekness from the US/North-based hipster. I have this 25-year retro theory (I explain below) – isn’t part of this a typically ironic/hipster laughter/fascination with the 80s? I do agree with you that race is involved, but I place race in a different place, not in a kind of neo-primitivism masculinity thing but directly in the irony part. I think that the particular brand of pop-culture-referencing that is so central in the classic picture of the post-Simpsons, post-Tarantino, post-gentrified Brooklyn white hipster is precisely irony. That is to say, it’s people who have less at stake that can afford to be ironic, which is why in Latin America, the only dirty hippies you find are from rich families, and nobody’s doing ironic send-ups of lower-class musics – they either slum or they don’t, but it’s too easy to be misidentified if people engage in ironic versioning.

This is a bit confusing. Summary: hipster consumption of global ghettotech is at least in part ironic, and its in the irony that race and a real sense of cultural superiority (not unmixed with genuine fascination) can be found.

Oh, and the Grand 25 Year Theory of Retro: all retro recycling hearks back to whatever was going on 25 years before, when it has already cycled out of what the cool kids do (o years), past what everybody’s doing (Andrew Ross’s black party – 1-3 years), past what a few pathetic hangers-on are doing (3-5 years) has finished the point of being made fun of as out of fashion (5-10 years) and has disappeared into oblivion (10-20) until its finally safe to bring back as retro, first by hipsters (22 years), then by everybody else (25 years). Think about it – the 90s had Tarantino taking up the 70s. Now, this summer, everybody was wearing flourescent streetwear and listening to Brazilian remixes of Miami Bass and “Sweet Dreams”… (Disclaimer: it might actually be 15 years or 30 years, what the fuck do I know.)

This is long, it’s late, and I have a fucking dissertation to write, but I’d curious to hear what you think.

Michael

Thanks for your thoughts, Michael. I don’t mean to imply that irony has nothing to do with it, but I think assuming that irony has everything to do with it might overlook some important things. And I like the way you phrase it — that certain folk can “afford to be ironic” — calling attention to the luxury of irony; another way to say it would be that certain folk have ironic modes of an engagement as a choice available to them, whereas others lack the same range of choices. I think there’s something crucial about that discrepancy in all of this.

As for your 25 year theory, I see what you mean, but I’m not sure that such a strict model really works anymore. I would have agreed with you in the early 90s when I watched pop culture fascination seemingly turn from the 60s (Woodstock ’94!) to the 70s (Pulp Fiction, etc), but then again, this was also right around the same time that the swing revival (Squirrel Nut Zippers, anyone) was, er, in full swing, etc. And at this point in time, it’s hard to sort out any of this fetishized periodization. I feel like many of the stereotypical styles associated with various decades of the 20th century now coexist in a constantly reshuffled set of signifiers, mainly used to market things. So the return to fluorescence (Fluo Kids, anyone?) that you see as an 80s thing has also accompanied a nu-rave aesthetic that we might also see as (false) nostalgia (and I say false b/c it’s the kind of nostalgia not for something one has experienced but for something one has seen represented as experience of the past) for the 1990s. Whereas in my college days (in the mid 90s), dorms would throw 80s dances, now you get 90s dances (and the 80s dance hasn’t gone away). So, I guess I’m wondering whether something has changed in the aesthetics of retro — not at all un-postmodern of course, in the Jamesonian sense — such that all (representations of) previous eras and their styles now flatly stand alongside each other as “cultural resources” (not to imply too much agency on the part of the takers) for those who have the luxury of making such choices.

At the same time, that the nu-rave aesthetic has also been driven by urban, underprivileged, black kids — take, e.g., those hyphy hoodies that were all the rage last year — is significant. Is that ironic? Unironic? Partially ironic? I dunno.

And at least in the south, and in Brazil, Miami bass never stopped being “a black thing.” Once it resurfaced as crunk (and, hence, as cool), I think it also became (re)available, even in NYC & esp for a generation once-removed from 80s bridge-and-tunnel imagery, for, as you put it, “wigger cred.” Even wiggerism, however, except for those whites who don’t really have the same range of choices (e.g., the underprivileged white folk who stand on corners imitating their black hustler brethren), today seems like something that has been loosed from its previous moorings in a certain kind of US racial formation. A lot to tease out here, obviously. So thanks for the continued convo…

shameless self promotion, but exactly on topic:

sliced up my hand at work and it’s hard to type….

do i get street cred now??

here’s urls for folks i mentioned, i pulled them of the cuff pretty much just to throw it out there, so i’m not trying to say they are representative or anything.

http://www.myspace.com/herecumdemfags

http://www.myspace.com/deadleeofficial

http://www.myspace.com/vippartyboys

http://www.johnnydangerous.net/

i guess i was partly thinking about camp as connected/contrasted with cool (and irony) in relationship to Kingdom.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camp_(style)

yeh i’m into the conversation between you and Lev. good stuff in there.

thanks for pointing.

want to write more but hand hurting.

hands feeling ok enough now for me to add commentary to above links.

i think it’s pretty obvious why Sgt. Sass (first link) is relevant.

esp. check out “batty oy bounce” and “faggot snap”.

what would Mailer say about queer black men’s place in his understanding of hipness?

do straight white boys appropriate gay black culture? yes actually.

…i also kinda want to go sideways and bring up stuff like ‘realness’ (scroll down) in compliment/contrast to that crossroads in pop media where blackface and gayface meet to produce Men On Film type characters played by straight men.

but that’s too far sideways maybe.

so, the second link is for Deadlee.

he’s also queering styles that are often seen as associated with (supposedly hetero) hyper masculinity and misogyny.

(ah and he did the soundtrack to the only gayngsta film i know of, On The Downlow)

then i put V.I.P. as the next link because there is something about gay white hipster/scenesters that are appropriating/adopting/camping Li’l Kim, et all, that complicates white hipster appropriation of misogynist othercultural styles in some weird ways.

you know?

interesting to me in context, anyways.

….and Johnny Dangerous (the last link) is doing sort of the same thing but with some differences in presentation.

sorry i know i’m handing you a difficult hairball of barely explored ideas, and is therefore hard to respond to, but i am not an academic (at all!) and have trouble being rigourously pointed with this stuff.

from a (black musicologist) colleague:

my dear colleague also recommends the following article as germane to the conversation —

Bucholtz, Mary. 2001. “The Whiteness of Nerds: Superstandard English and Racial Markedness.†Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 11(1): 84–100.

I’m gonna say now that I’m still quite new to the whole concept of blogs and interacting to posts, so please pardon me if I’m breaking with code by responding to previous posts…the subject is a curious one and I felt a need to blab about it from my side of the fence (even if it’s only to get it out of my system).

I think there is a certain faction of “white” listeners/makers of music that falls under the category of “global ghettotech” who perceive their interests as being a means of working through inherent internalized racist perceptions. This is maybe what you touched on when quoting some things from Norman Mailer’s hipster mainfesto, though I haven’t read the original yet so don’t know for sure. Of course this only seems justifiable if linked hand-in-hand with actual physical involvement amongst the culture at large who’s music is being explored.

Having said that, minus the direct involvement with the culture itself the original intention seems hollow or at the very least misguided and unrealistic. One comment from this post that rings so profoundly is where you speak of the disconnect between the audience (and the culture surrounding them) to that of the makers of the music (and the culture surrounding them). This is something that anyone who has grown up in the USA in the last 3 decades has dealt with, most likely without directly perceiving it, through television–>MTV. Whether that be an upper-class white kid in suburban LA exposed to Run DMC or a poor black kid in Chicago exposed to Nirvana. Or a teenage Japanese girl living in Tokyo exposed to Michael Jackson for that matter! Which brings me to my next point…

It’s as if, for sake of a unified existence, a sense of wholeness, each of us who has been exposed and affected by this barrage of cultural art forms, images and soundwaves, we must seek completion through the direct consumption of the “Other” that so occupies our conscious and subsconsious minds —> http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oswald_de_Andrade —–> Manifesto Antropófago (Cannibal Manifesto)

Without that direct contact with the source there is always going to be a great longing for a connection. I feel this is what many of us raised in modern industrialized “First World” nations wind-up experiencing. Werner Herzog, sums it up in this clip:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k0GrFfEsWFc

I just want to end this by saying that in the short time I’ve known you, Wayne, there’s nothing that’s ever struck me as being hipster about you.

Not to be the anti-intellectual hater in the group, but I think that playing race into the situation is misguided. If you wanna talk high-minded semiotics, you’re probably better off starting with the generalized effects of overstimulation and economic alienation. I don’t think most people that you’re referring to have any sense that the music that they’re jumping around to is “black”; people just know that it bumps. It’s unclear where your insinuation of racial mockery comes from. House music and techno owes as much to a bunchy of goofy WHITE europeans at Formula 1 after-parties as it does with sweaty, BLACK beats in detroit. That people are interested in music with a groove is nothing new, and the fact that it owes more of its racial genealogy to AFRICA and South America is more an accident of the history of western music than a racist posturing.

Moreover, “white” music, in America, by which we mean mostly music derived from folk traditions of the British Isles, has a good deal of currency with “hipsters” whatever that means. People still have a great deal of fondness for romantic, ballady music and folksy root’n tootin’ hoedown shit. I’m sure that if you wanted to you could pull some non-caucasian forefather into the spotlight to prove the concept that cool is black, but, to allow some legal terminology, such a root is likely to be quite remote cause. Where are the accusations re: lionization of Johnny Cash, Woody Guthrie, Earl Scruggs, etc?

The concept of musical segregation is a historical artifact of popular-music criticism’s genesis in the early days of rock and roll, church burnings, Nashville and Frank Sinatra. It is pretty anachronistic in most contexts today, and nowhere is this more true than the global electronic music scene. Ghislain is a particularly horrible example. As someone who is fairly intimate with Montreal’s music world, I can tell you that these insinuations of latent racism are likely to be met by the multi-ethnic milieu composing Montreal (and most urban electronic music cultures) with a (well-deserved) dismissal or, even, disgust.

People like to dance. They like new beats because it produces a pleasurable sensation when their brain clicks into the new rhythmic pattern. They like global music for the same reason that they like mangos, chipotle and curry – because they’re fucking good.

I’m not discouraging the elevation of popular music into the analytic schema of Theory, but be reasonable.

As a PSA, don’t use the word wigger. It make’s you sound like a fucking 10 year old in his brother’s Alice in Chains shirt.

—–Churn. Re: Gentrification,

You’re right. This is not a black/white issue and neither is it motivated by racial mimicry. To illustrate, i will point to those cities with which I have actual experience. the East side of LA was/is mexican, Hollywood was Jewish and million other things, the Mission was/is Mexican, Mile End and Plateau were Portuguese/Greek/Jewish, Williamsburg was similarly Jewish/multi-ethnic. While I understand that the issue of gentrification is often posed in terms of race, it is not racial, it’s economic. Poor musicians, artist, bums and students are broke, along with people stretched on the wheel by the economic system. Why not go after the homosexual community for the same thing? They’re first movers in gentrification by a mile. Anyways, that’s my 2 cents.

Now, excuse me, I’m gonna go paint myself up with some blackface and rap my way over to the chicken and waffles place across the street, son.

BLECH.

Bill, I see your points — and the last thing I was trying to do here is reify a sense of black and white (indeed, i wonder whether you actually read the post) — but I also think it would be foolish to pretend that all that’s going on in the circulation/representation/popularity of what, for better or worse, is frequently cast as “black music” is that people like “good” stuff.

At least from where I’m coming, which is an admittedly intellectual project of analyzing the way musical practice and representation relate to the (re)production of racial ideologies, I find it really unproductive to pretend that fantasies of the primitive don’t still animate way too much of the activity described above. But I suppose in some sense I’m biased. I just happen to think my own bias is better than a subconscious desire for authentic experience, which, sorry to say, I still think is very much at play — not to underestimate, as MBQ notes above, some of the more ironic, playful engagements with ideas about self and other.

I find your criticism muddled and confusing. “Ghislain is a horrible example” of what? In case you haven’t figured it out, I’m a friend and a fan of Ghislain; I’ve played parties in Montreal along with Ghislain. I think what you say about the multiracial scene in MTL rings true, and I think Ghis offers a great example of how to navigate the necessarily tricky, historically-freighted terrain of working with music cast as black. (Please pay particular attention to how I ended that sentence before coming back at me with allegations that I’m drawing a color line that doesn’t really exist.)

I could go on, but I think your rant rather deconstructs itself. I’ll leave you with a paraphrased nugget from Hamlet:

Isn’t black music simply the music actual black people make and/or consider theirs? Is there any other way to define black music I’m not aware of?

By that definition, Birdseed — which is not an unreasonable one — the term “black music” loses any meaning — perhaps rightly so — since “actual black people” play a vast range of music. Such a paradox calls attention to the utter fiction of race and of essentialist theories of culture. And yet the term “black music” circulates and resonates nonetheless, embraced by black people and non-blacks alike, and tends to refer to specific genres and modes of performance, often cast as black because of their rhythmic emphasis / orientation and, I’d contend, often carrying the traces of American racial ideologies.

I’m less interested in wondering whether there is any such tangible / identifiable thing as “black music” (since, in a sense, there isn’t) and more interested in how discourses and ideologies of race circulate through music, as well as how musical practices themselves inform as they appear to reflect our ideas about racial difference. See, e.g.

There is no there there, as I’ve put it before (apparently applying a questionable Gertrude Stein quotation). Even so, that doesn’t mean that we should pretend that black music, like the fact of blackness itself (as Fanon put it), doesn’t have real effects in the world — that people don’t behave as if it is a real thing, a stable thing, a true thing, a beautiful, desirable, wonderful thing.

It’s an interesting theory (in the link and the post), but I’m still a bit uncomfortable with the idea of socially assigned roles in a context like this – no doubt they exist, but there’s a possibility of reading the idea (as in Adorno) as rather dismissive of actual culture and creativity. There’s plenty of black musicians in history who’ve made brilliant “hot rhythm” music, out of their own community and for their own community, often reviled by mainstream society – are they all suckers to the slave owners for sticking to stereotype? (In that case, aren’t all cultural expressions that differ from group to group somehow wrong and in need of eradication? You’d be out of a job!)

It’s more subtle and complex than that, Birdseed. I recommend you read this. All the way through.

As for “wrong and in need of eradication,” no one’s saying that. I’m not sure why you’d take such a step. Sounds creepy to me. On the other hand, if you mean that I’d be out of a job because racism would no longer exist, well, I could live with that. I’m sure I could find plenty else to write and teach about — indeed, I already do.