In a recent issue of the SEM Newsletter (March 2007, to be precise), Phil Bohlman addressed the issue of cultural translation and how it presents a paradox to ethnomusicologists — or perhaps more broadly, to those of us who mediate musical representations in myriad ways (including via links and mp3s):

Should we understand our acts of translation as encounter? Or as appropriation? Encounter, even in its colonialist history, was meant to close the gap between self and other, clearly with power skewed toward the self. Appropriation, in contrast, often led to the eventual elimination of the gap, once the other was stripped of her identity. Inescapably for ethnomusicologists, this paradox bears the weight of ethical and moral imperatives.

Bohlman continues,

Such imperatives are all the more reason to take cultural translation very seriously and to search for the means and methods that respect both author and reader, both original performers and those who listen and perform at a distance.

Ruminating on this while downloading a slew of new mixes from across the musiconnoisseurosphere, I can’t help but think about certain “nu” movements on the old ‘osphere (and, simultaneously, its meatspace analogs, outlets, and sources) — movements which I find promising and yet which, especially given my own involvement, also cause me to pause in “inescapable” knee-jerk reflexivity.

These new directions in musical production, circulation, and representation have been described in various ways, some giving more pause than others. If you’ve DL’d and/or danced to “baile” funk, kuduro, kwaito, and various global hip-hop/reggae/techno offshoots in the last couple years, then you probably have some sense of what I’m referring to: in contrast to more purist spheres of consumption and circulation (say, within reggae or hip-hop or techno), which can maintain a stubborn separatism, new movements in (and of) post-colonial pop/dance music have tended to swirl together via various eclecticist, ecumenical, open-eared (and perhaps open-minded) middlemen (and women). This embrace of “other musics” is not entirely unlike that in the “world music” circuit/market more generally, except that somewhat different notions of authenticity appear to animate the activity in these distinct, if overlapping spheres.

In what we might call “trad” “world music” discourse (e.g., deriving largely from the marketing attempts of the 80s and 90s) — the language and images and ideas mediating the explorations of Paul Simon, David Byrne, and Ry Cooder, as well as such record labels as Rough Guide and Putumayo — authenticity is often conferred onto the traditional, the pristine, the timeless, the exotic, that which has been untainted by capitalism, by Western cultural imperialism more generally, etc. Whereas the recent movements on the music blogosphere that I am thinking of tend to do the opposite: never mind these false ideas about purity, they seem to say, we want our global crunk, we want hybrids and fusions, we want mirror-mirror reflections and refractions of New World and Old World, North and South, East and West, we want music concerned with the future as much as (or more than) the past, we want drum machines and synthesizers and samples, for the local is always (trans)local and the global is (always already) here.

Of course, both “world music” discourses I am discussing here remain tethered to certain notions of (foreign, if familiar) rhythm, especially those figures that light up the “African”/”American” regions of our imaginations. But let’s leave that aside for a moment. (If, however, one is looking for an interesting perspective on this issue, see, e.g., Deborah Pacini-Hernandez’s “A View from the South: Spanish-Caribbean Perspectives on World Beat” [pdf].) Moreover, we might go further and note the preference among devotees of the new “world music” for the low-fi and DIY rather than the slick and commercial — a form of authenticity that dovetails with even as it departs from previous ideas about what, say, an African musician could or could not do in the studio in order to remain sufficiently “African” for local and foreign consumers alike. The question of “production values” and access to, say, Scott Storchian tech remains a vexed vortex for determining authenticity. (And, just for the record, as I’ve said before, there is no there there when we’re talking about the a-word.)

With regard to naming this new world music, one might simply gloss the constellation of genres as “urban dance music” or “global urban dance music” or some such neutral descriptor (as I and some ethnoid colleagues have done in framing our panel proposal for SEM 2007). Some have attempted to give it flashier names, hearing something of a global “ghetto” archipelago. (The number and spatial dispersion of myspace musicians identifying as “ghettotech,” for instance, is quite striking — and they’re not all tongue-in-cheek, or at least in the same way [same cheek?].) Still others nod to nu-metal, nu-rave, etc., to proclaim (or claim) a contemporary “nu world” movement. A brief, imagistic quotation from MIA describing her upcoming album for the Guardian would seem to point at, if not to shape, such a position: ‘Shapes, colours, Africa, street, power, bitch, nu world, brave.’ That last word, of course, despite perhaps a nod to Aldous Huxley, prompts us to wonder (or perhaps simply accept?) how much courage is involved in marketing the “nu world” to the New World (i.e., US consumers).

As the Bohlman quotations with which I began suggest, there is a fine line between encounter and appropriation, between, if you will, the half decent and the mad decent. As such, I’m deeply interested, being a middleman of sorts myself (for better or worse), in the ways we might understand the ethics of blogging about, mixing, zsharing, and otherwise mediating new world music (or whatever u wanna call it). Might we think about such activities as translations? If so, what is gained and what is lost?

…

Thinking about this should not necessarily give so much pause, however, that we stop uploading and downloading and DJing and dancing, and so toward that end, allow me to recommend some good outlets along the lines I’ve been tracing out above. There are the usual suspects of course — such globe-trotting champions of “other music” (and, yes, [always also] “self music”) as /Rupture and Maga Bo and Benn Loxo and their ilk — as well as these dudes, sin duda. Ghislain Poirier’s myspace page, for instance, currently describes his own distinctive, voracious, low-end theory as “Cosmopolitan ninja bass & chunky digital dancehall”! (I like that.) But let’s take this opportunity to note some other, perhaps lesser known, but quite chunky cosmopolitan ninjas in their own right —

Montreal’s Masalacists, for example, have been producing a stunningly consistent and stimulating set of mixes and podcasts and parties around the idea of global dance music, including some deeply detailed posts filled with outgoing links for more info & more music. Sometimes it seems — and this is where we get into the murky waters of translation — as if they give shape not simply to Montreal’s imagination of the world, but Montreal’s imagination of itself, the sound of Quebec undergoing the kind of demographic and cultural changes that have reshaped so many metropoles in the post- and neo-colonial era.

Similarly, London’s DJ Vamanos, who recently cooked up a guest mix for Masala and who kindly welcomed me to London by taking me to an excellent documentary on Cuban hip-hop at the ICA, seems to express in his posts, shares, and mixes that London is (eagerly) coming to polyglot terms with its imperial legacies and contemporary diversity and, moreover, that Britishness might accommodate itself to less provincial notions of self and home.

Of course, there are other ways to read and hear these things too.

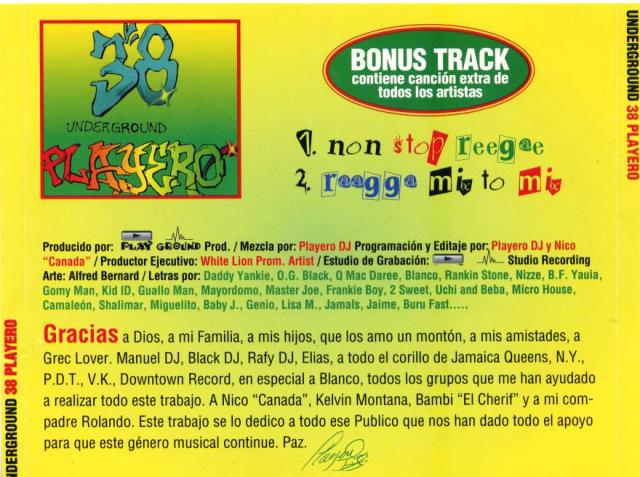

When I first saw the name “Vamanos” — a misspelling of Spanish’s first person plural imperative, “vamonos” (i.e., “let’s go”) — I have to confess that I winced a little. For all the efforts at understanding a foreign cultural context, the name seemed to bespeak a certain ignorance, or perhaps the sort of irreverence through which certain idiot-savvy bloggaz attempt to mask their more cynical efforts. I have since come to appreciate it, however, as explicitly marking an inherent distance. It reminds me of similar (mis)spellings on the proto-reggaeton mixtapes of DJ Playero, for example, which might title one side “non stop reegae” and another side “raagga mix to mix” —

— whether ignorant or irreverent, the names make the same point that Playero’s dembow / melaza mixtapes make: they gesture directly and unmistakably to dancehall reggae while noting, quite obviously, that there is an act of translation underway. New contexts demand new texts.

And then, of course, there’s the slightly awkward URL for Señor Vamanos’s site: ghettobassquake, tapping into the “ghettocentric” discourses I noted above. As much as I appreciate the class and race politics of identifying with and championing the music of the poor, glorification of the ghetto is a vvvv tricky thing. These days I can’t get beyond this scene in my attempts at hermeneutical understanding of the complexities and contradictions swirling around such a project (even if one thinks it through a little more than John Brown).

Obviously, this is murky territory. Let me conclude, then, by pointing to one more interesting, and aptly named, node in the network: the Netherlands’ Murk, who recently cast his 3rd pod (or something like that) in a series that has explored — not unlike some of Dr.Auratheft‘s work — a kind of EU-era, post-911 (anti?)orientalism. “Ranging from dub to hiphop, dancehall, breakcore and tekno,” as Murk describes it, Jihadcore

includes scraps of Mutamassik, Filastine, Appa, Tomatito, Sizzla, Elephant Man, T.O.K., Seeed, Nettle, Dead Prez, Timbaland, Sly & Robbie, Calibe, freesound.org, jury-rigged DIY beats and several mysteriously labelled Moroccan & Egyptian CD-R’s.

Let me say first that I dig the mix, as well as the first two in the series. I especially like how Murk lets us hear how those utterly occidental genres (if we’re gonna think in Huntingtonian terms), reggae and hip-hop, serve as global filters for the nu-oriental. At the same time, there’s something weird (once again) about the mixture of serious engagement on Murk’s part (which is no doubt required to beef up them bellydance beats) and what seems like flippancy. What makes the CD-Rs in question “mysteriously labelled”? Is it because they’re in Arabic? Just wondering. I wouldn’t know how to tell from Murk’s text whether they were actually somehow substantively mys/mis-labeled or whether Murk is mucking around (critically?) with the notion of ignorance and the sometimes seemingly impassable distance of foreign language and culture. Maybe that’s how he wants it, suggestive like the music. Which is fine. But how about some pictures of said CD-Rs, how about the story of how they passed into one’s hands, how about attempting to tell us a little more about the poetics informing the mix?

…

I’m not asking that all of us in our various guises and roles and such simply become ethnomusicologists. (Far from it — though that’s the subject of another post.) But I’d like to see more of us consider the kinds of questions Phil Bohlman so trenchantly puts to us —

Should we understand our acts of translation as encounter? Or as appropriation?

Well, I’m one of the “nu” people referred to in the post who despise traditional world music and “folk” music. I used to have a radio show from 2003-2005 where I introduced my sleepy, ice-bound University town to the reggaetons and kwaitos of this world, and I’ve certainly had to face the issue of cultural translation many times. It’s all too easy to think of yourself as a transparent mediator, when in fact you’re consistently rejecting a lot of material as having the “wrong sound” for instance…

Two things I’ll say in the new “movement”‘s defense though. Firstly, unlike the old “world music”, the new stuff is almost always locally produced and locally popular before becoming globally so. The stuff we pick out has consistently been a hit in the producing region first, which ought to point to a certain measure of correct interpretation. (In fact, I’ll go so far as to say that strong local flavour, together with the percieved modernity, is the defining characteristic of the new music, which is why you’ll see me calling it “local urban music” rather than “global urban music”, making it include Crunk but exclude boring korean hip-hop clones, so to speak.)

The second thing is that the internet is a unique opportunity to “eavesdrop” on these local scenes. It’s possible to “listen in” without interfering a lot these days, and very easily too with all the tools at our disposal. Makes no difference later, mind, but I think it’s brought with it a realization of exactly what goes on within communities elsewhere, and a much greater multitude of fans and mediators than ever before, hopefully leading to more diverse sources and a truer picture.

I definately see the problematic nature of the two statements above, and I hopefully will have time to discuss that later.

Right, sorry about the rushed end of the last post. What I meant to say is, once the genre has indeed “gone global” and once the people we listen in to are aware of our presence, the same problems are going to occur as with traditional world music – we have the money and the power (as Mr Sche would put it) and the music will start to adapt to our needs and tastes. I guess what I’m saying is that in this context appropriation is a bigger problem than encounter (if I’ve understood the two terms right).

Oh, and re: the ghetto thing, I don’t use those terms myself but I understand where they’re coming from. See, whereas traditional world music pulls material from all sorts of social classes – ruling elites, peasants (a clear favourite) or in David Byrne’s case the middle classes – the “nu” (or as I would put it, “anti”) world music is consistently the music of the urban disenfranchised working classes and the urban poor. And even more specifically, the young urban poor.

In fact, in terms of music, “urban” and “ghetto” mean pretty much the same thing, I’d suggest.

Thanks for the comments, Birdseed. You make some great points.

I really like your distinction between “local urban music” and “global urban music,” though one thing I was trying to get at is that these are really quite mixed up. That’s one reason I like how a term like “translocal” can get at the ways that locals can travel and be in conversation. (Plus, it’s much better than that awful neologism, “glocal.”)

Your bigger point about these genres gaining local popularity before they’re brokered to a wider audience is a good one, too. That would seem to distinguish between, say, something like kuduro or funk carioca and the US/Euro-directed studio experiments that characterize a lot of what Peter Gabriel and Putumayo, etc., have been cooking up for years (never mind the Bonde do Role phenomenon).

And I also think you’re right that the internet has a lot to do with this, and perhaps that ‘urban’ and ‘ghetto’ are simply synonyms (tho, I’d contend, synonyms that communicate rather different takes on things, representational strategies, etc. — if sometimes speciously, as in “urban” radio, where it seems like a euphemism for “black”). One problem here, though, is that I think we’re kidding ourselves to pretend that the young urban poor of the world have access to such technologies. Although the tools become more accessible all the time, there are obviously (middleclass) middlemen who operate in both local and global spheres and bring such sounds and images to us via youtube, myspace, blogs, etc. So I think it’s important to maintain some vigilance around all of that. A whole lotta translation a gwaan.

Oh, absolutely no doubt. Source criticism is an important factor in any research. You have to be able to read between the lines, but I’d say even some of the most skewed reinterpretations can sometimes lead you on to better material eventually.

I once “discovered” a genre (Manele, modern romanian gypsy music with influences from arabic pop and house) because some prole-hating teenage hacker had made a computer virus which displayed the message “Manele sucks” (or something) when triggered. Read about in on a tech site, did a few searches and voilà , the kid had achieved precisely the opposite of what he set out to do. :D

—

One thing I do think we all need to keep in mind is that neither “world music” is exhaustive. There’s a lot of music which is very interesting that neither us or the other crowd ever want to touch. The grown-up, simple, working-class music for instance, your Lukthungs and Bachatas and Cantopops rarely get a look in. (Just like, I guess, the country and mainstream pop of our won societies rarely get analyzed.) The cosmopolitan styles that are analogous to western genres other than hip-hop or house are also generally not selected – Indonesian lounge music or malaysian metal derivates… And then there’s all the straight copies – no-one actually likes those meek korean boy bands. Even with this “new” selection process the vast majority of the music created stays in the local market it was made for.

Wayne, great post, and a lot to process. I wonder about this “middleman” idea–from a certain perspective, a middleman becomes necessary in capitalism precisely when there is a gap that can’t be crossed. The distributor can’t make a profit distributing from/to this market (buying diamonds, selling underwear), so a middleman group steps in who can. In Africa, we’re talking here about Lebanese in Sierra Leone, Asians in Uganda, etc. A multitude of sins gets covered in this process.

For example, why can’t Cooder, Putamayo et al make a profit buying whatever’s being produced in cyberspace or the back alleys of Havana or London, commoditizing it, and selling it back? Because there are gaps between the ear of the manufacturer, the ear of the producer/worker, and the ear of the consumer. Thus the need for translation.

Wayne. This is interesting. Firstly thanks for the props and thanks for the email – I don’t feel dissed, though you do owe me a pint ! Theres way too much to comment on here so I’m going to focus on one element.

Regarding Ghettoisms, I agree with what your saying. When I was trying to think of a name for my blog I gotta confess I never really analysed the linguistics of the word Ghetto. Maybe because its not an overly used word here in the UK and has more connotations attached to it in the states and other countries. I guess I used the term in more of a musical context within in the music that I love. Like the way its used in genre titles like Ghetto House, Ghetto tech – insinuating lo-fi lo-tech DIY bass and beats driven flavas….

Moreover I like to take a light hearted approach to blog writing but now I’m thinking shit, maybe more than 10 people actually read my crap and have an opinion on the title.

If I am a “middleman” then I’m interested in what other people think. Is the title ‘Ghetto Bassquake’ treading a fine line in respect of the blog’s actual content ? Should I change it ? I’m not that precious about it.

Oh, forgot one important category in the listing above – music that conforms to all the anti-world criteria (local, modern for the time, young, working-class) but that was made before the view changed in the late nineties. There’s much less interest in, say, latin freestyle or beach or dangdut or seventies soca than there is in comparable genres that were already mass “discovered” back then, your afrofunks and reggaes. I guess they get stuck between us who want new, excting music and those who, back then, discarded it as irrelevant and westernized.

Or maybe they just didn’t see it? ‘Cause I think one crucial issue when talking about translation is the fact that our previous experiences not only prejudice us but also determine, to a large extent, what we actually see/hear. I did a philosophy of science course a few years ago and one very persuasive paper that stuck in my head was about the fact that what we percieve with our senses is actually different from person to person depending on what we’ve trained ourselves to understand. One person sees a microscope slide of gray blobs, another sees nerve cells undergoing meosis, and can’t be made to just see the gray blobs again. One person hears an unpleasant throbbing racket, another a rather tepidly produced piece of progressive house with tribal trance influences.

I think it’s highly possible that there’s plenty of stuff going on that we’re not seeing, because we don’t yet have the tools to understand it. Likewise, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that this nu thing is happening now rather than at any other time in history, not just because the sounds are coming around now due to technological changes (most of them arrived almost a decade before they were globally picked up), but also because we’re in a position today where they’ve suddenly become relevant and comprehensible.

The radical left (and let’s not kid ourselves here, practically all of us mediators have left-wing views) has realigned itself in a couple of decades from fighting a monolithic capitalism to fighting a myriad of identity opressions. Ideas of cultural identity, difference, represantation, identity groups and rights to self-definition have become increasingly dominant. Some people would say that stuff became less important with the new global focus post-9/11 but I think unlike previous foreign-oriented periods in radical history this one is very closely tied in with domestic issues and ideas of identity. The fight against imperialism is today intertwined with the fight against racism and the wish to let all people shape their own culture and destiny…

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that this is the climate where nu-world (or whatever) has emerged. Us translators today have a wish to take a step back and let the musicians themselves do the talking, defining, producing, identity-making. It’s possibly naive, but I think at the very least it’s a decent thing to attempt.

Wayne– I was truly surprised when I read your claim that hiphop, reggae, and techno have “more purist spheres of consumption and circulation” and “can maintain a stubborn separatism”, especially considering that you are contrasting these 3 genres with a nu-scene or approach which you describe as “various global hip-hop/reggae/techno offshoots”.

the metaphor of translation is provocative but ultimately unrewarding i feel, since it obfuscates the fact — critical to this discussion — that a lot of theses nu-world tunes circulating in Anglophone (& Francophone, big up MTLcrew) scene have lyrics which are not translated into the languages of those among us doing the swapping. So there are specific, nonmetaphoric issues of translations we should be discussing here…

the terms ‘middleman’ and ‘mediation’ are charged too, since they imply dialog, which, in nu-world is usually nonexistent, although i love the call to consider the implications of blogging & zsharing & mixing.

Murk emailed me multiple times about his ‘Jihadcore’ mix, which contains music i’ve released on my label & music I’ve produced — but i have no interest in downloading or listening to anything with a title as ignorant and stupidly sensationalistic as that one. complete with desert photo & faux arabic font!

It makes me deeply uncomfortable that a white northern european lumps our shit under a totalizing & exoticizing rubric of ‘jihadcore’.

on one hand i’m reminded of the spice merchants of venice.

….how they used the spices of asia, africa, and the americas to create new social, cultural, and economic spaces (the middleclass) for themselves.

a musical economy.

and on another hand, it reminds me of the way taussig describes the magical economy of an area centered around the putumayo river of colombia in shamanism, colonialism and the wildman (huh…..second time a post of yrs has made me fly there in my head).

taussig talks about highland shaman collecting magical power from the (‘wild’) jungles and (‘savage’) shaman of the lowlands, and bringing it back to the highlands to cure the ill effects of La Envidia.

the power of the magic (and the image of the shaman) comes out of how colonialism was/is inscribed onto the bodies of what is now Colombia, and so does the Envidia it assuages.

it’s a magical economy.

(that’s a really bad gloss, but my writing skills are not that great…)

i guess i’m seeing the musical economy yr talking about in alot the same manner.

like, music is collected from the young urban poor and then used as a balm for assuaging…….’whiteness’?

i don’t know.

spice merchants.

i sure didn’t mean to imply that hip-hop, reggae, and techno are in any sense stable formations or able to successfully resist fusion, influence, etc. indeed, much of my research and teaching and writing has to do with how these genres (esp hip-hop and reggae) interpenetrate and inform each other. what i was referring to with the “purist” sentence was the existence of scenes-within-scenes which attempt, stubbornly, to police the borders of the genres to which they’re devoted. surely we can all conjure our own examples of hip-hop or reggae or techno connoisseurs who pretend that anything outside of a certain “(hard?)core” is not (authentic) hip-hop or reggae or techno. such purists are, of course, nothing but the moldy figs of their generation, upholding orthodox ideas about genre limits for various (often vain) reasons. although these purist “cores” are largely more imaginary than real (for if we push at their boundaries, they fall away quite easily), i do think they exist in some sense, though i certainly was not attempting to glorify or reify such spheres.

i was simply seeking to contrast the existence of such stubborn isolationism, which we can easily find lurking on devoted messageboards and blogs and club nights, with the more omnivorous approach typified by a lot of this new world music activity. for example, we might contrast — on, say, a monday night in central square in cambridge — the “straight-up” reggae offered up by voyager1 at the phoenix landing (which nonetheless ranges from roots to bashment, and used to feature an hour of hip-hop in the middle) with the eclectic outlook at beat research across the street, where DJ C and flack are as likely to play roots and dancehall, as dubstep, bhangra, jungle, hip-hop, cosmopolitan ninja bass, etc.

i appreciate your point about “nonmetaphorical” meanings of translation in this context as well. no doubt these are critical. to be fair, bohlman discusses several forms of translation in his piece (via ricoer, et al.), though i am here picking up on the idea in a more general sense. i would, however, add — pace walter benjamin — that even seemingly “literal” acts of translation have deeply metaphorical dimensions. but such is language: most terms are charged. (the word is the ideological sign par excellence, argued volosinov.) it’s for precisely these reasons that i welcome the francophiles in all of this — not to mention your own spanish-tinged contributions — and that i hope for more middlemen/mediators from outside the US and europe (who are no doubt out there, if currently off my radar/sitemeter).

w/r/t “jihadcore,” i hear what you’re saying and part of my discomfort — which dominic gets at with his invocation of “spice merchants” (and, oh, how the language of spice/sabor/flavor infuses world music discourse) — has to do with the lack of transparency or reflexivity in such an endeavor. at the same time, perhaps i would like to provide something of a generous (as well as critical) reading of what murk is up to. it seems to me, for instance, that the “stupidly sensationalistic” dimensions you point out might also serve to finger the similarly stupid sensationalism of plenty of contemporary jihadists who press that very charged and serious term (for members of the ummah) into the service of their own narrow ends — or, for that matter, plenty of casual orientalists in the hip-hop, reggae, dubstep, breakcore, etc., scenes. perhaps that is more generous a reading than is warranted, but i would like nonetheless to embolden, and to burden, music makers such as murk to continue to do what they do, but to think about it. hard.

your perspective, /rupture, of course, as someone sampled into the mix, is necessarily different than mine. though i would argue, exoticism and sensationalism aside, that your (and your cohorts’) music survives such appropriations handily, and perhaps even resists them in the mix. they cannot be totalized. they can and will be rearticulated in future performances.

finally, let me just admit that i am myself guilty in this post of a great deal of lumping together. but the last thing i want to (wrongly) imply is that everyone i mention in this post is up to the same thing, employing the same representational strategies, etc. still, i think it is worth considering all of this activity as interlinked, though you may be right that “translation” only goes so far in explanatory power, and may obscure as much as it reveals.

for those reasons, and many many others, i’m grateful for all comments. this is stuff i’m very much still in the midst of thinking through, of making sense of, of translating for my own little corner of the web and the world.

keep em comin’

i’m concerned with the degree to which these critical, crucial subtleties are transmitted from the scene outward. and, yeah, let’s just go ahead and get it out in the open–this is a scene, and this entry and comment section are proof of both its expansion and some type of solidification process.

at the center of this, in my opinion, is this whole ‘jihadcore’ thing. i agree with both wayne and jace. my gut tells me to think that wayne’s ‘generous’ reading is probably right, but that title is a dumb idea for the reasons jace cites, and i think it’s a good place to draw some sort of line. pointlessly charged shock value isn’t really needed by a mix of sounds dismissed by dumbasses at my old college, texas a&M university, as ‘fuckin terrorist music’ (got that one called in more than once on my radio show there).

I agree with Jace, Wayne – we should not promote sensational marketing tools like “jihadcore” in the first place (meaningless and unnecessary), and secondly – if we want to open up things – we have to prevent using identifying and totalising concepts. Because this is the real (white) European problem: always taking the short road to fixed identities.

Thanks for adding your perspectives to the mix, Quieto and Siebe.

I’m wondering, though, Dr.Auratheft, since I hear resonances between your own mixes (esp, those arguing for “Post-European Dialogues in Sound” and “Why The Mediterranean Should Be Allowed In”) and those by Murk: what’s the difference? Is it all in a name? Or is there more in terms of presentation, accompanying text, musical selections, musical manipulations? I think it would be helpful if we could try to distinguish those approaches we find productive, open, non-totalizing, etc., from those we do not. Where do we draw Quieto’s “sort of line”?

Of all the various actors/DJs I’ve linked to above, there are certainly some approaches that I find more promising than others (/Rupture and Auratheft among the better of the bunch). Often this has to do with challenging rather than reproducing stereotypes, and with a certain sort of self-reflection that seeks to undercut (or at least make transparent) the power relations undergirding all this circulation and representation. As I think out loud about this, I appreciate others — especially those of us also involved in the enterprise — adding their 2 cents. So thanks again, and let’s continue the conversation, in comment threads and in posts and mixes, etc.

aside: just yesterday i was thinking of Auratheft b/c i found an excellent cd called “Flamenco & Musique Soufi Ottomane: L’Orient de l’Occident. Hommage a Ibn Arabi Sufi de Andalucia, Imagine par Kudsi Erguner.’ on the Al Sur label.

would have been a perfect addition to Auratheft’s mix exploring resonances btwn flamenco and qawwali/sufi music.

A lot to say and not that much time to write, so I’ll limit that comment to one counter-fact.

Concerning Funk Carioca and the argument of music being accessible to western audience is the one that already received success, I would like to point out that it’s not what’s going on.

Everyday in Rio, djs including the famous ones (Sandrinho) are dropping mp3s on dozens of sound system’s websites. And from what I know, it represents maybe only 20% of what’s actually produced by favela’s music producers. This websites are really easy to find because they’re tagging most of the mp3s downloadable and one who’ll spend 30 min on google can find them. For example : http://www.searchmpthree.com/index.asp (this one isn’t even dedicated to funk) or like this one where I get a lot of new stuff: http://www.funktotal.com.br/

So what I’m saying is that, in the case of Funk Carioca, that assomption is wrong. The numbers of compilations accessible in the western product distribution circuit are really limitated and are of course representing the “hits” of one style. But you can in fact really easily access a great variety of producer’s work via internet without a medium. I’ll add that a “middleman” such as Gorky, who’s doing the beat/dj for Bonde Do Role, is actually downloading his funk on this websites and that of course the big tracks are quite kept off the download by DJ/producers so they can keep up to their reputation during the balls.

I can also go on about the kuduro situation but I have to go back to work now! ;)

Perhaps “it is all in a name” – that’s the (political/artistic) problem I was referring to. To come up with a name too soon is an everyday strategy of identification/commodification – and by commodified reproduction the concept/the art loses its aura (i.e. “auratheft”). The same argument goes for the political situation in The Netherlands/Europe. The questions raised in my mixes are passionate plea’s for exploration and complexity, rather than conclusions and slogans. I’m trying to open up what is closing rapidly; I’m trying to make liquid what tends to congeal. I’m not sure if I’m succesful in doing so and I’m not sure where it will take me – I hope to find little pieces of answers in sound/ideas and little threads of routes/approaches in life. Like when I discovered Maurice El Medioni: his one hand playing “oriental” (but not really) and his other playing “latin” (but not really), combining a multitude of cultures/influences, however never identifying them – the aura is just there ( and I’m not talking about “authenticity” or “originality”).

I think a lot of us are doing/exploring the same thing. (Yesterday my pal Jos of Amsterdam band The Ex described the visions he got when he witnessed /Rupture’s multi-layered set in NY recently – and isn’t The Ex doing the same thing? As a sharing consumer – not an artist, I’m trying as well, although I lack the talents of /Rupture and/or The Ex.) Anyway, it is all in a name for sure, but there’s much more to it. It’s like swimming up the river and discovering the delta’s of possibillities… Just pass on the knowledge and hesitate to define, I guess. Thanks for providing space, Wayne, and keep up the good work here.

ps. Yeah /Rupture, that record was sent to me after I produced the mix. It’s excellent indeed. Thanks.

Well put, Siebe. (& thanks for calling my attn to the Benjaminian dimensions of your nom de mix — I think I’ve been reading it as more about the “aural” than “aura”; this gives me another perspective from which to hear what you’re doing/exploring!) As much as a lot of us are exploring the same sort of thing, I too want to resist naming it. That’s one reason I’ve used so many descriptors here, including some misspellings of my own, and why I implicitly critique the whole “nu” thing as another co-optation, reification, commodification, as much as it seems to put its finger on something, a zeitgeist perhaps.

And point taken, Guillame. I didn’t mean to imply that there are always middlemen getting in the way (sometimes thankfully), and I’m definitely enheartened by the growing access to (digital) tools of production and distribution. The remarkable reach of such local styles as Rio funk and, say, Chicago juke — genres which themselves have yet to be embraced nationally and yet which find international audiences all the same — would seem to have as much to do with local producers getting their stuff out there as with cosmopolitan mediators moving things around.

At the same time, the digital divide is still real in lots of ways: I wonder about that other 80% and why we’re not hearing it. Also, for a lot of people who aren’t willing to Google for thirty-minutes and would rather just visit their fave mp3blog, I’m afraid that those compilations (as well as Diplo’s mixes) remain the main touchstones of the genre. For those reasons and more, I’m glad that folks like you and Vamanos and gScruggs and eStark and others are happy to dig around — in Rio and on the net.

Figured it might be time to put my two cents in…

The title, which seems to affront a lot of people, wasn’t meant all that seriously. Yes, some more thought could have been put into the title, but it is merely an eyecatcher, and in that sense, it seems to work perfectly.

The intention of putting out these mixes is purely, as Wayne states, to bring new sounds to people who aren’t willing to do the actual digging themselves. In the same sense, it it not a priority for me at this moment to do more digging into the political undercurrents of the Middle-East and North-Africa. (not that I am totally clueless, but the focus here is on the music. I am not trying to make some sort of profound statement. I understand that this might automatically occur by the combination of title, image and sound, but does this mean that whenever a consumer/ dj/ artist encounters something he likes and decides to use it, he or she immediately needs to know everything about the background of said item, so as not to affront anyone? Sometimes sound is just sound.) This is encounter, not appropriation.

And lastly: I hold no illusion that I’m up there with the likes of the Soot crew or the good Dr. A.; just a very enthusiastic fan here. So, next time, perhaps, more consideration on my part and less taking things all that seriously on other people’s parts?

many thoughts, not much to add but a small riff, a train of thought that took off

the “middlemen” and “spice merchant” metaphors or images can be further complicated by the fact that historically such people and groups are often themselves diasporic: jews (lots of places), lebanese (in the caribbean), chinese (in indonesia, philippines, Jamaica), and/or folks of mixed ethnicity from within and without the communities they are in the middle of.

(Sean Paul: middle class Sephardic Jewish and Portuguese and African and Chinese)

In different ways, such diasporic/merchant groups or mixed-ethnicity groups complicate the story of exploitation, although not erasing it (or de-racing it).

To try to continue to the point: Whatever their ethnicity, the multitude of sins I mentioned as associated with “middleman” groups has to do with putting up with dangerous working conditions, making do with slimmer margins, accepting greater instability in lifestyle, etc. The position is circumscribed and limited. Capitalism is built on being able to measure success via its asymmetry. Because producer A flies first class and producer B drives a Honda but producer C has a crappy kids’ bicycle, we can rate their relative value at this time and in this market. The strange thing about “middlemen” is their ability to morph bodies without organs, to translate so apparently seamlessly that they appear to erase the difference and help us forget how the labor turned into money.

see, John, now that’s interesting. Because part of that sounds to me like collapsing the middleman into the top-down power structure. And while that may function somewhat like you describe, I’d pull in rupture’s points (especially as expanded on his blog) to suggest that there is far more ‘horizontal’ cross-pollination, or at least transactions going on on other axes than the one I see in your words above.

It’s not really about ethnicity, it’s about position. If you only see two groups – the powerful and the powerless, then the middleman inevitably are cast as facilitating that relationship. I resist describing all middlemen (I wish I had a better word for it) as shills for the powerful, which is what I see in the “help us forget” sentence at the end as saying. Some may act this way, but others are aligned on different axes, and those are also meaningful.

the interview rupture quotes from is talking about music as something other than (or more than) labor. I don’t think that’s false consciousness.

this may be a silly point, but having been in addis ababa for about a month now, completely unable to update my blog due to what seems to be government intervention and completely unable to access music due to a lack of broadband, i can’t help but wonder about the technological aspect of all of this. i can’t dig around the internet–nor can anyone in this country. the music i hear in ethiopia is so darned ethiopian (with random mainstream–and only the main-est of mainstream) that it is “purist” by default.

the ethiopiques series is so distanced from what actually is going on here–the ever-growing multi-cd collection is available to folks outside of ethiopia, but beyond chasing down mulatu astetke himself, it’s near impossible to find any of that stuff here.

speaking of mulatu, every night on “FM” (there’s only one station) mulatu asteke plays a huge mish mash of what he calls “african jazz”–music he classifies as jazz, taking from all over. he’ll sometimes bring in tunes by “forenguch” (foreigners) or the “habesha” diaspora. i think ripley’s point about avoiding binary positioning is imperative and allows for a discussion of mulatu’s position as a very different type of middleman–someone who is not downloading tunes off the internet, and his audience is only within addis ababa and the surrounding area.

anyhow, i’m trying to get over a horrible cold…thanks for giving me something good to read (and the page loaded fast–a relief!)

I’m not sure the middleman is necessarily always someone powerful oppressing the powerless, but she sure as hell is one im potentia.

It’s slightly paradoxical, but the more popular the material she picks out becomes, the more oppressed the people she’s championing actually become! Because once the tastes of the west (or the national elite, or another powered group) become the dominant source of revenue, especially via the middleman, then the middleman’s position towards the artist is significantly strengthened power-wise.

Of course, in most traditional world-music and folk artist-middleman relationships, it doesn’t even go that far – in both the world-beat and folkey worlds, the word of the middleman is completely law because his choices are the ones that will mean the difference between success and failure. He will often produce, record, publish and promote the artist and be his sole source of revenue. And just as much, his hegemonistic ideology will be the one that will determine the (monetary?) value of the musicians output…

I think we need to start thinking about creating a code of ethics, or a set of principles, that will make sure the power rests with the producer as much as possible and set us appart from previous generations of middlemen like those described above. I’ve got quite a few ideas for points to include.

Erin, I don’t think that the Ethiopiques nor the Terp Records are ment to portray current Ethiopian sounds which are played on radio’s or in Addis Adeba disco’s, but are ment as a novelty -to pull historic sounds back to the present or as a current discovery-. Whether Ethiopian society follows the same curve is not the point of these releases. I was talking to Terrie of the Ex on friday about Ethiopian music and Terp’s part in it. He simply made it clear that he only releases the music of people that he feels are authentic and not by a general consensus of status or fame. Afterwards, him and Andy were playing modern Ethiopian disco tunes, heavily filled with synthesizer sounds. You could understand why the Ethiopian folk music -like any older style of music witihin any country- in dying out within the country of origin, yet is making a diasporic journey to countries outside of that musical context. Music will always have a diasporic nature to be transported into new horizons and unexpected place.

Current and prime example, the Chutney Soca! On how soca music recently was taken to India though the Indian/Hindi population living in Surinam and the carribean isles. Soca rhythms and punjabi/bhangra united in a interracial marriage of sound. Bizarre yet so completely on topic, considering how world music is becoming more and more filled with fusions.

it’s good to hear people like most of you here, who take various world styles and turning them into a global intermeshing sound with each a different context of location and movement. If the emphasis would always be on the same identity – the curse of many genres alike- it would be deflating the whole eclectic global idea imho.

The murk mix; though it carries a title wrapped in bad pun, it is kinda funny how the put the Rupture stamp on this 45 mins. surely there’s a eenie tiny bit of pride Jace? ;)

You raise some good points, Sebcat. (And let me note too that I really appreciate the perspective offered by Erin to which you respond.) Perhaps a better comparison for Ethiopiques would be one of the many labels offering reissues of 60s and 70s funk, jazz, & psych recordings from all over the place. In that sense, they present less a picture of Ethiopia today (but don’t try to tell that to Mulatu) than a picture of Ethiopian counter-culture yesterday.

At the same time, I don’t see why heavily synthesized contempo disco tunes should not fit the bill. Here’s where we get at the problem of the definition of authenticity. It’s a determination that will always, inevitably be utterly subjective and ideologically fraught. I’m sure that Terrie has “good taste” (though I can’t use the phrase without thinking Bourdieu), but it would be better if he — or Francis Falceto for that matter — actually laid out more clearly (and reflexively) how they decide to confer authenticity on one thing and not another. Maybe they do, and they’re clearly quite thoughtful about the enterprise, but you would seem to imply here that authenticity might naturally be opposed to popularity or commercial success, which it often is in certain discourses, but which tells us little about the music and more about the arbiters.

Cosmopop that how i call ” nu world music ” since 1995 on France-Inter & radio Nova ;

and Cosmomix is the name of my ” genre ” of Dj set , but global beat seems to

be the favorite naming… yves thibord Dj

what i find interesting about ethiopia is that the ethiopian folk music is NOT dying out within the country. be it zefen (secular) or mazmul (sacred), both traditional and contemporary (probably the heavily synthesized stuff you heard) are super popular. music played with only traditional instruments: masinko, krar, etc. is also heard everywhere. it’s a bit of an acquired taste, but it’s so prevalent that a western girl like me must develop a bit of a relationship with what first sounds quite dissonant.

the ethiopiques series presents a style of ethiopian music that was never considered folk music. the diasporic popularity of that music seems, to me, to be connected with the international popularity of jazz.

i think that wayne is right–the ethiopiques is very much a portrait of ethiopian counter culture. music made during a time when, as someone said to me the other day, no one wanted to leave ethiopia. those who were into mulatu were considered to be looking outside of ethiopia–not a popular view at the time.

mulatu’s radio show is still a little out there…

i happen to be a big fan of guraginya music-if you can get your hands on “hosay basa”, do. but you better make sure you know the proper dance moves. no “estkitsa” (amhara shoulder dancing) to guraginya music!

2 things on this ethiopia mini-thread

1) Terrie/Terp is, uh, ‘the real deal’… The Ex’s most recent CD (the band in which Terrie plays baritone guitar) is a collabo with ethiopian saxophonist Getachew Mekuria — *Getachew* initiated the collabo, asking The Ex to be his backing band and release an album on Terp, not the other way around. that’s just one of countless examples of how they collapse distance and avoid the pitfalls of foreigner/native authentic/fake insider/outsider pop/artsy, etc. not only do they often invite african musicians to tour w/ them around europe, they’ve toured in ethiopia several times — the influences are flying in all directions!

interpenetration without (negative) interference, the way we like it…

2) ethiopiques isn’t exactly ‘counter-culture’ — the series is internally quite diverse, from huge former pop hits to more obscure stuff. several of the comps even feature *police bands*!! (any band actually composed of

pigspoliceman cant be counterculture, by definition :)Looks like the NYT has finally caught on —