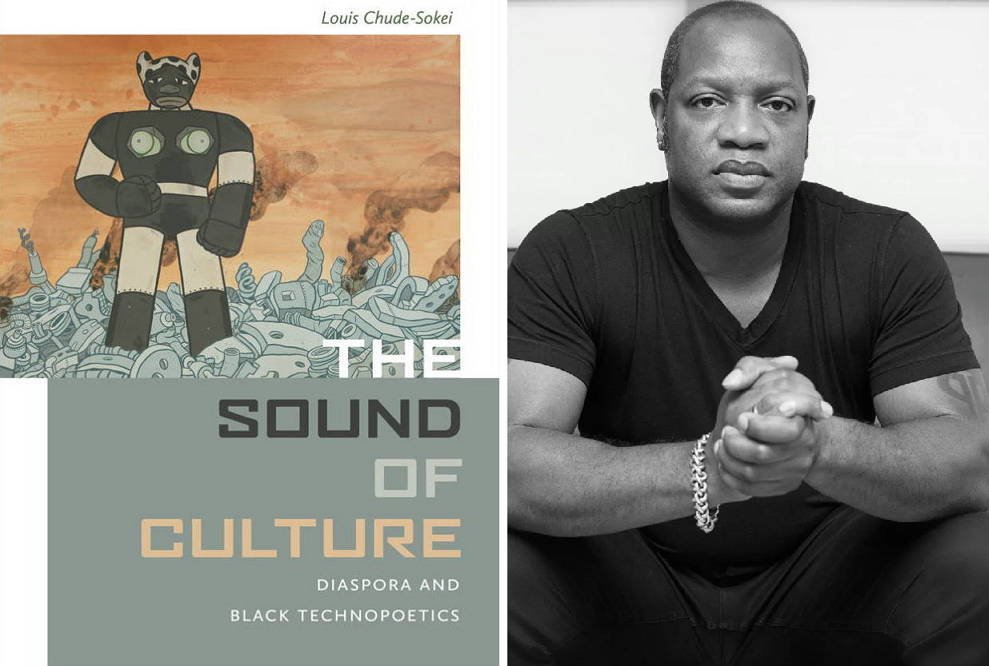

Last summer I was invited by Small Axe, a journal I have long wanted to write for, to take part in a book discussion of Louis Chude-Sokei’s engrossing, ambitious The Sound of Culture: Diaspora and Black Technopoetics. I’ve enjoyed Chude-Sokei’s perspectives on dancehall, Nigerian 419 scammers, and Bert Williams for years, and I was already planning to give the new book a good read, so this was an excellent opportunity. The journal was looking for more of a “response” than a traditional review, so I decided to focus on the critical musical threads of the book and, in particular, how they might contribute to discussions in music (and sound) studies, especially for those of us concerned with histories of diaspora and race (and, yes, reggae–among other things).

My response, “Listening to the Sound of Culture,” appeared in Small Axe 55, and you can read it in context here alongside some great articles. But here is a separate PDF of the proofs for your convenience, and I will paste the introduction below to whet appetites. Read my response — then read Louis’s book!

Louis Chude-Sokei’s The Sound of Culture: Diaspora and Black Technopoetics offers an intricately nested account of the historical relationship between race and technology, or in his words, “a broader reading of the historical and cultural context that allowed those equivalences between blacks and machines to be sensible in the first place” (5). As that framing suggests, the work offers an entwined genealogy of black claims to humanity and human fears of robot uprisings, with profound implications for how we continue to imagine the boundaries of humanity. Works of science fiction and key historical vignettes serve as Chude-Sokei’s primary exegetical texts, but he notably places black music–or more specifically, sound production–at the center of his account. What makes such an approach “structurally and philosophically possible,” he argues, “is the awareness that black music–from jazz to reggae, hip-hop to electronic dance music–has always been the primary space of direct black interaction with technology and informatics” (5).

Chude-Sokei is careful to stress, therefore, that “this is not a book about music”; rather, music serves as “a thread linking the various texts and contexts, secondary only to science fiction, which itself is subordinate to the mutually constitutive dyad of race and technology” (6). More to the point, this is not a book about music because the author is more concerned with sound, which is to say, with black music as media, or as audible interaction with technology. Without dismissing other forms of black invention, Chude-Sokei contends that music represents an exceptional domain of black technological practice: “the primary zone where blacks have directly functioned as innovators in technology’s usage” and “a space where black inventiveness has rarely or successfully been questioned” (5). Hence, to focus on music “as a space of sound and sound production is to reorient our listening … toward how blacks directly engage information and technology through sound” (5).

This focus on sound brings into relief a rich and complex history of interaction undercutting the persistent myth that blacks and technology are somehow opposed, or that blacks enjoy so little access to technology that such interactions can seem “either rare or adversarial, as in the well-known folktale of John Henry” (6). Chude-Sokei cites the so-called “digital divide” as a recent reiteration of this spurious story of black technological lack, a story that withers quickly in the face of the musical record: “Funny thing about these notions of race or blacks as having been victims of a digital divide is that in the very period that term gained such currency as to have become cliché, blacks in the Caribbean, America, and Europe were busy generating the most sophisticated electronic music and technology-obsessed music subcultures in history” (6). As that jump from the Caribbean to the wider world would suggest to scholars of electronic music, this is an analysis that builds on the remarkable resonance and influence of the Jamaican soundsystem and all that follows. It is more than convenient that one vernacular name for a soundsystem is simply a sound, a term that, as Chude-Sokei is quick to emphasize, “foregrounds technology and specific cultural interactions with it” (7) not unlike a great deal of Jamaican music itself, especially dub.

While it is true that the “mutually constitutive dyad of race and technology” persists as the core subject of Chude-Sokei’s book, I would like to focus on the text’s crucial musical threads in order to highlight how The Sound of Culture reorients specific histories of music, offers new openings for musicology and sound studies, and makes a case that the power of an audible, creole technopoetics can remake our very conception of the human. If, as Chude-Sokei posits, the black diaspora has generated the “most necessary theorizing and politicizing” of where we draw the lines between humans and machines “as a product of its extensive thinking about the African slave as an automaton” (8), and if, as he elaborates, this profound philosophical work has been no more forcefully put forward than by dub reggae, then there is a great deal to listen for in this work and all it brings into the mix.

[Read the rest…]