Gilles Aubry’s The Amplification of Souls is a meticulously composed and conceived “audio-essay” (Aubry’s term) on Kinshasa’s charismatic churches and the broader soundscape they inhabit and inflect. I reviewed the CD, along with its 80 page booklet, in Issue 371 of The Wire (January 2015).

As usual, I am posting the final draft I sent my editor, or what I like to call the “director’s cut.” You can see the piece as it ran c/o Aubry’s website. Special thanks to David Font-Navarrete — ethnomusicolleague, friend, artist, and author of the incisive “File Under ‘Import’: Musical Distortion, Exoticism, and Authenticité in Congotronics” — for helping me think aloud here.

Gilles Aubry

The Amplification of Souls

ADOCS Verlag CD+8K

As speaker hum and empty plosives congeal into a stuttered mic-check for Jesus, a slight squeal suggests the looming threat of feedback. Because so many of Kinshasa’s churches are open-air affairs, the rumble of motorcycles and automobiles accompany the ambience of a band slowly tuning up and worshippers gathering. Preachers punch through the din with bursts of noise louder than anything else, the flat lines of distortion making palpable the power of their authority. Handmade PAs hit their limits as microphones bear witness to the possession of souls and of space. And then, sudden quiet save for the faint buzz of the sound system. Speakertowers of Babel from the Heart of Darkness, respectfully recorded and remixed for headphones and museums thousands of miles away.

The jump cuts are jarring, reminding that this is no straightforward documentary. The voice of the artist, Gilles Aubry, resounds here too. The Amplification of Souls is, according to its careful and copious framing, Aubry’s “audio-essay” on Kinshasa’s religious soundscape. Congolese charismatic churches are a laudable focus given the immensity of the phenomenon and the general indifference to it in the wider world, perhaps because megachurches and prosperity gospel seem more essentially American than African. Attempting what the artist contends is “a material-based form of cultural interpretation” the work stands as a studious, self-aware approach to sonic ethnography. Aubry’s project is so steeped in reflexivity and rigorous attention to the sounds and their contexts and meanings, it clearly seeks to pre-empt perfunctory charges of appropriation. “He doesn’t even understand what we’re saying,” says a churchgoer quoted in the liner notes, “Them, the whites, they record anything.”

What constitutes understanding here is a crucial, vexing point. A dozen minutes in, the tongues begin. The glossolalia is striking in itself, alien and arresting and enjoying an undistorted sonic clarity in contrast to the punchy preachers. It also seems to mirror the varied textures of the audio-essay itself, composed of multiple sound sources created by different people with different objectives: church services and evangelical street campaigns, radio and video, cooking and football. At one point, a burst of traditional music, full of clapping and ululation, points more toward continuities than contrasts, while the appearance of local rap and meandering Hawaiian guitar suggest other Others to be heard. All the while, Aubry’s own voice emerges in the layering of samples, their stereo spatialization, and the inevitable narrative arc that emerges from his rearrangement of such disparate sonic documents.

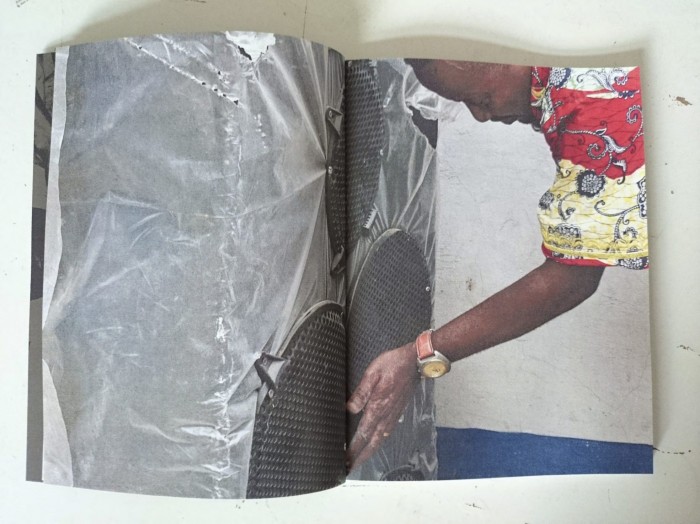

Presented as academic sound art, The Amplification of Souls comes with an 80 page booklet including an interview with Aubry that contains the phrase “neo-colonial representation” in its subtitle. It also boasts an essay on “The Sonic Materialities of Belief” by a musicologist and cultural anthropologist which notes, among other things, that Congolese charismatic movements themselves “appropriated” the patina, and hence the power, of noise and distortion from Pentecostal missionaries. Performed previously as a sound installation and now as an ongoing set of public performances, Aubry’s remixed recordings stand at once as an impressionistic refraction of Kinshasa’s soundscape and as the material embodiment of sounds that he would like to let speak for themselves. One way that Aubry does so is to pair his collage with a 34 minute excerpt of a spiritual deliverance service that provides a great deal more context and less composerly initiative, though the profound act of framing remains. In another show of transparency, Aubry’s original recordings of the service in full have been archived online.

Even so, what makes this anything other than churchy Congotronics? Why choose Kinshasa instead of Kansas City? Or, for that matter, Berlin? Not only does the city that Aubry calls home play host to numerous charismatic churches itself, some are even Congolese. Obviously, the specific site of these recordings is crucial to their circulation as art in Europe and the US, but it is deeply ironic that, against the coolness of Kinshasa trance traditionalists like Konono No 1, Aubry must seek out possessed Christians to locate the hot exoticism Western audiences expect. How would Kinshasa’s charismatic communities receive this project? Would it sound like understanding? Should that guide the way audiences elsewhere experience it? The emphasis on sound as material culture suggests that we’re not meant to attend to the content so much as the deracinated affects of the audio. Perhaps glossolalia itself offers an answer. Does the lexical register matter when all that we’re waiting for is the outbreak of the unintelligible?

Wayne Marshall

[listen to excerpts at earpolitics.net]