I reviewed Tropicalia: Ou Panis Et Circencis, a re-issue of the classic salvo in Brazil’s tropicalia movement, for Issue 367 of The Wire (September 2014). Happily, this one’s also a nice chunky review; nice to get a little leeway on the wordcount for a verbose dude like yours truly. Here’s a director’s cut of sorts, somewhere between the semi-final and final version.

Tropicalia: Ou Panis Et Circencis

Various

Soul Jazz Records CD/LP

A charming but sardonic cha cha for Christopher Columbus, a rock anthem quoting Latin liturgy as it bears witness to the hungry poor and the bloodstained tables of the rich, a dada-esque word puzzle that possibly alludes to Batman, a dreamy bossa nova telling listeners to eat ice cream and learn English (in Portuguese) — these are just a few points of contrast and conversation threaded through an album that aspired to no less than naming and giving voice to a new cultural movement, and succeeded spectacularly.

Yet despite its firm place in the history of Brazilian music, Tropicalia: Ou Panis Et Circensis, the coproduced and collaborative creation of Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso, Tom Zé, Os Mutantes, Nara Leao, Gal Costa, Rogério Duprat, and many more, has long suffered from a conspicuous lack of circulation beyond Brazil. All the more strange considering the album’s uncanny incorporation of UK psychedelic rock into a Brazilian idiom.

“We were ‘eating’ The Beatles and Jimi Hendrix,” remembers Caetano Veloso in his memoir Verdade Tropical, invoking a foundational imperative to cannibalize — culturally, that is — proposed in the 1920s by modernist poet, Oswald De Andrade. Taking to heart Andrade’s call for Brazilian artists not to imitate but to devour whatever they encounter, in the late 1960s the tropicalistas would initiate a cultural turn by their brave commitment to a voracious aesthetic at the height of a military dictatorship that would later arrest and exile both Gil and Veloso (who would return years later as luminaries, with Gil eventually serving as Minister of Culture in the 2000s under Luiz Inácio Lula Da Silva).

In the decades since its resonant debut, much ink has spilled over tropicalia’s significance, and listeners outside of Brazil have been introduced to the music via retrospectives released by Soul Jazz, Luaka Bop and others. Still, the album’s singular expression of the movement has yet to enjoy widespread reception on its own terms. Clocking in at just under 40 minutes, with segues and sequencing, Tropicalia wants to be heard as a unit, in a single setting, or over and over.

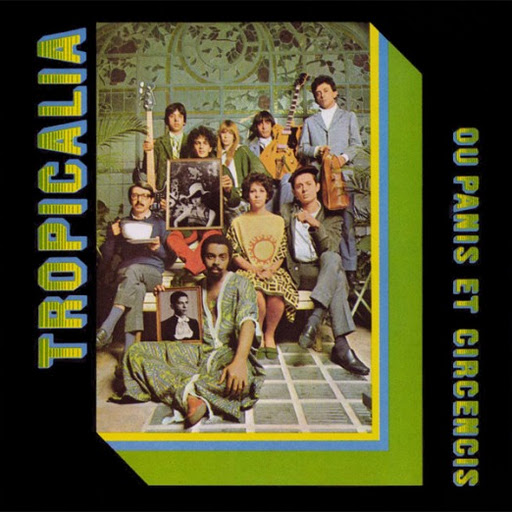

As if responding to the dearth of access to physical copies for so long, Soul Jazz is only releasing the album in physical form and with faithful, facsimile repackaging, including the original art (an inclusive, symbol-laden, family-style photo), unusual approach to song credits, and dramaturgical liner notes from the back of the record sleeve. They do so with reason. As with other concept albums of the day, Tropicalia was produced as a total package and placed remarkable emphasis on acknowledging the contributions of all involved while underscoring the collaboration at the heart of the project. Beside the song titles sit the songwriters’ (first) names, followed by the performers’ names in parentheses. Writing and performing each other’s songs, and honoring as they blur the distinct voices of the group, Veloso, Gil, et al, appear more as a true collective — a movement, even — than a conventional group.

Boxed in by an opposition between the West and the Rest that they wanted neither to deny nor accept, the tropicalistas developed a pointedly diverse sound by drawing as much on resilient local accents as international codes. “We wanted to participate in the worldwide language,” Veloso recounts, “both to strengthen ourselves as a people and to affirm our originality.” Eschewing homogenous fusion for a chunky syncretism, the music on Tropicalia moves with conviction from psych rock fantasia to tweaked bossa nova, cheeky mambo to treacly ballad, sometimes within the span of a single track.

The album is tight but never stiff, at once made supple by ebullient performances and substantial by the critiques smoldering between the lines. The opener, “Miserere Nobis” sets up this double-edge straight away with its church organ intro and chorus plea to “have mercy on us”, deploying Catholic referents and what Veloso refers to as “noble images enveloping a political commitment that is far more implicit than stated”. As the track shifts from quick, jangly strumming, rolling drums, and a double-time shaker to a staccato, reedy riff, Gil rehearses a simple set of ideals in Portuguese: “Hopefully one day, one day…for all and always the same beer” and that “the table of the people has bananas and beans”. Language aside, “Geléia Geral” would hardly sound out of place on Pet Sounds with its elaborate, layered arrangement, except for the samba section that erupts half-way into the song. The chorus, “Ê bumba iê iê boi”, in arch-tropicalist fashion, slyly coaxes a rock-inflected “yeah-yeah” out of a folk song from the North East of Brazil.

Elsewhere, using a Dylan inspired mix of plainspokenness and oblique metaphor, Os Mutantes’ “Panis Et Circensis” explicitly needles the complacent middle class during a moment of crisis and possibility: “I unfurled the sails on the masts in the air / I set free the tigers and the lions in backyards / But the people in the dining room / Are busy being born and dying”. After a couple minutes of haranguing the bourgeois, the hurdy-gurdy dirge slows to a stop, as if the power went out and the record stopped spinning. Seconds later, the “busy being born and dying” line returns as a mantra chanted over a galloping, Beatles-esque backbeat complete with twittering trumpets. The music gathers speed until it crashes with a hard tape splice into the mundane din of clinking glasses and inane chatter over muted strains of Blue Danube.

If elaborately orchestrated rock, especially the kind of multitracked whimsy and ambition of Sgt Pepper’s, is the album’s most obvious exotic touchstone, then arranger Rogério Duprat, who stands as a central member of the motley crew on the album cover, is the collective’s George Martin, providing a swell of strings or bursts of fanfare when needed, or, say, a bass clarinet figure bubbling briefly in the left channel. Duprat’s soaring arrangement for Veloso’s cover of Vicente Celestino’s “Coração Materno” supplies crucial support to a triumphant tribute, reanimating reviled schmaltz in order to undermine a prevailing elitism that the tropicalistas wished to resist.

Occasionally the lyrics and sonic signposts are less veiled — as when Gil and Veloso ironically sing the praises of Cristóvão Colombo “who, to our delight, came with three caravels”. Then there’s the pathetic pomp of the final track, “Hino Do Senhor Do Bonfim”, a nationalistic anthem which eventually brings the album to a close with eerie moans, the cavernous knocks of a distant cannon, and silence. It doesn’t take a weatherman to know which way a military dictatorship might interpret such a work of smoking agitpop.

Wayne Marshall

[hear clips at the Soul Jazz site]