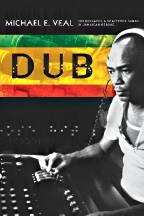

Been working on a review of ethnomusicologist Michael Veal’s recently published book on dub (it’s called Dub [BUY!]), which I will share with y’all before too long; meantime, as I jot down some excerpts, I thought I’d share some of my favorite passages — insightful thoughts and neat narratives and such.

To wit, a nice summation of different directions in Jamaican pop circa the 70s:

The sylistic evolution of Jamaican popular music along both local and transnational lines was a complex and intertwined process; in terms of the aesthetics of production, however, reggae developed in two general directions during the 1970s. One direction was represented by musicians like Marley, Peter Tosh, Toots and the Maytals, Jimmy Cliff, and others: these were the figureheads anointed by the multinational record industry to introduce Jamaican popular music to the international audience. For this reason, their music was often recorded at better-equipped studios outside of Jamaica and was marked by high-end production values, more sophisticated chord progressions than were the local norm, and rock/pop stylizations such as electronic synthesizers and lead guitar solos. As with most pop music, there was a strong emphasis on singing, and specific songs tended to be associated with specific performers. Song lyrics tended toward themes of social and political justice filtered through the religious vision of Rastafari. The biblical undertones of this vision translated onto the world stage as a universalist sentiment that struck a chord with post-World War II American and European rock audiences.

…

Although it came to sell significantly abroad, another direction in which reggae developed was represented by musicians producing music largely aimed at the local Jamaican audience, associated during the 1970s and early 1980s with producers like Bunny Lee, Linval Thompson, Joe Gibbs, Junjo Lawes, and the Hookim brothers. How did the music differ from that of performers like Marley and Tosh? DJs — vocalists who rapped over rhythm tracks — were becoming nearly as popular as singers inside of Jamaica; in terms of song lyrics, however, the difference was not always so pronounced. The Rastafari-inspired lyrical themes were shared by both camps, such as those addressing African repatriation, the benefits of ganja (marijuana) smoking, the heroism of Marcus Garvey, quotations of Scripture, or the divinity of Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie. Certain topics tended to be more prevalent in the local sphere, such as the ever-present “slackness” song (generally sung by DJs) focusing on sexual topics, the “lover’s rock” genre of romantic reggae (which actually had roots in the music of Jamaican immigrants in England), the songs addressing the political violence that was engulfing Jamaica, or songs relating to current events in general. One clearly important difference between local and international reggae was in their respective sites of consumption. As opposed to attending the concerts staged abroad by musicians like Marley and Tosh, most Jamaicans enjoyed music in dancehalls and at outdoor dances at which recorded music was provided by mobile entertainment collectives known as sound systems.

Possibly the clearest difference between the two types of reggae was in the sound, and it is the sound of Jamaican reggae that I primarily address in this book. In contrast to the music aimed at the international market, the production values and seemingly “virtual” construction of much of the music aimed at Kingston’s sound system audiences probably seemed downright errant to many American, European, and upper-class Jamaican listeners at that time, whose listening tastes were conditioned by the naturalist values of much rock and roll and soul music. This music, in contrast, drew attention to itself as a _recording_ in a particular way. These Jamaican singers did not always conform to the chord changes of a song, and sometimes even sang in a different key altogether from the musicians. Vocalists didn’t even always sing; many times they casually rapped over the rhythm tracks as if they were carrying on a conversation in spite of the music underneath. The vocals also sometimes seemed strangely discontinuous; no sooner would a singer complete a stanza of a song, before a different vocalist (usually a DJ) began shouting over the music in apparent disregard of the original vocalist; the varying fidelity made it clear that these vocalists did not record their parts at the same time. The music also seemed oddly mixed. The bass sounded unusually heavy and the equalization strangely inconsistent, as the sound veered back and forth from cloudy and bass-heavy to sharp and tinny. The individual instruments didn’t play continuously, but zipped in and out of the mix in a strangely incoherent manner. At a dance or on the radio, it seemed as if you could hear the same rhythm track for hours on end. …

Essentially, the artist-based marketing of Jamaican musicians in the Euro-American audience by multinational corporations did not prepare one for the often bewildering complexity of a music that, in its natural context, was multiply elaborated by a multitude of voices moving between the fluid sites of stage, studio, and sound system. Even within Jamaica, popular music has moved in and out of phase with radio networks, with music producers and radio programmers sometimes holding strongly contrasting ideas about what constitutes acceptable or appropriate broadcast quality and/or content. It was these rougher qualities that were sometimes deemed in need of “smoothing out” by multinational record labels, in their attempt to market reggae internationally. As such, they are largely absent from the Jamaican music most familiar to non-Jamaicans. Ironically, however, the same musical choices that made local Jamaican music sound so “pre-professional” to mainstream Western ears were simultaneously visionary and deliberate. The approach Jamaican producers and recording engineers took to the production of music would make a subtle, structural, and long-term impact on world popular music in subsequent years, providing openings for new practice in the areas of form, structure, harmony, orchestration, and music production. It illustrates that postindependence Jamaica has been an important source of material and sound concepts for the international music industry, with reggae itself being, in the words of Louis Chude-Sokei, “a vehicle for the dissemination of larger ideas about sound, oral/aural knowledge, and technical innovation. (4-6)

I’d say that’s a clear and informative summary as well as a sly, persuasive argument that makes dub the kernal, the center, the impetus even, of what comes to be known as dancehall — and then of “world popular music” more generally (which I wouldn’t really disagree with, though the process was a messy and multinodal one). Veal seems to elide over eras a little easily here, and he sets up value judgments (only to knock them down) from a norm residing well within the (how imaginary?) world of “mainstream Western ears” (I know why he does this — he’s writing a book for musicologists and works in a “music” department — but I wonder if we should continue doing this sort of thing); despite a few quibbles, however, I find it a cogent passage. In just a few paragraphs, Veal imparts a much deeper sense of what reggae is than most people tend to have — (Isn’t it remarkable how often reggae gets tagged with the “all sounds the same” pejorative? A classic confession of cultural ignorance.) — and provides an orientation to dub’s significance for the wider musical world.

Here’s another good one, one which tells you again about the kind of book Dub is:

All the talk of circuits, knobs, and switches can distract one from the fundamental reality that what these musicians were doing was synthesizing a new popular art form, creating a space where people could come together joyously despite the harshness that surrounded them. They created a music as roughly textured as the physical reality of the place, but with the power to transport their listeners to dancefloor nirvana as well as far reaches of the cultural and political imagination: Africa, outer space, inner space, nature, and political/economic liberation. Nevertheless, this book will focus on those knobs and the the people who operated them, in order to develop an understanding of the role of sound technology, sound technicians, and sound aesthetics within the larger cultural and political realities of Jamaica in the 1970s. (13-14)

then there’s this sharp statement on the prominence of bass in JA pop and the stylistic transition from rocksteady to reggae, a moment that has needed more elucidation than most periods in reggae history:

Ever since the R&B and ska years, when sound system operators pushed their bass controls to full capacity in order to thrill and traumatize their audiences and have their sounds heard over the widest possible outdoor distances, the electric bass had grown in prominence in Jamaican music. The first Fender bass had been introduced into Jamaica around 1959 by bassist/entrepreneur Byron Lee and by the rock steady period, Jackie Jackson had emerged to define the instrument’s role more precisely. As rock steady began to slow down into what became known as reggae, it was this instrument that became the key to the new style. Structurally, reggae was partly common practice harmony and song form, and partly a neo-African music of fairly rigid ensemble stratification in which the fundamental ingredients were an aggressive, syncopated bass line, a minimalist (but highly ornamented) drum set pattern, and a chordal instrument (usually guitar and/or piano) playing starkly on each offbeat eighth note, elaborated by a syncopated “shuffle organ” emphasizing the offbeats in sixteenth-note double time. The “one drop” became standardized into a minimalist pattern in which the bass drum emphasized beats 2 and 4, the snare (playing mainly on the rim) alternately doubled the bass drum or improvised syncopations, while the hi-hat kept straight or swung eighth note time. There were also several other popular patterns and variations, such as the popular “steppers” rhythm in which the bass drum sounded on each beat while the snare played interlocking syncopations, or the “flying cymbal,” which imported the offbeat hi-hat splash of disco music and fused it with the one drop.

Although rock steady is generally considered to have “slowed down” into reggae, it actually accelerated (via the double-time shuffle organ) and decelerated (via the half time drum and bass) simultaneously. It also tightened considerably, as rock steady had at times retained some of the ensemble looseness of ska. Because of this juxtaposition of downbeat and offbeat, along with the tighter ensemble texture, the net effect of “roots” reggae (as it came to be known) was simultaneously of midair suspension and firm grounding, of density and spaciousness, of weightiness and weightlessness. (32)

Well put, I’d say.

& this is an interesting, and insightful, interpretation of the role the DJs played in breaking apart notions of song, thus suggesting (or indeed, “prefiguring”) some of dub’s profound approach to form:

… the process of stripping songs down to their essential components must be understood as substantially intertwined with the practice of deejaying; while studio engineers were beginning to use the mixing board to open songs up from the inside, their work was clearly prefigured by the deejays who destroyed song form from the outside. Rapping, chanting, and shouting their laconic improvisations often irrespective of harmonic or formal changes, and asking their selectors to “pull up” (stop and restart the record) at every opportunity, the deejays were rudely and creatively disrespectful of song form. Ultimately, the aesthetic of fragmented and superimposed vocalizing that would become such an important part of dub music could be thought of as at least partially inspired by the performance style of the sound system DJs and selectors. (56)

and this pithy bit on (musically-mediated) notions of “Africa” is well worth repeating:

Drum & bass was thus one of many instances in which musicians of African descent began to deconstruct and Africanize the Western popular song according to whatever ideas prevailed about which musical choices constituted “Africa” in their particular location.

further —

despite the de-emphasis on Africa as a lyrical trope (although this also began to reverse in the early 1990s), the emphasis on dance music has allowed ragga to become arguably _more_ polyrhythmic than the one drop orientation of roots reggae, drawing simultaneously on Jamaica’s neo-African drumming traditions and the accumulative logics of digital sampling as influenced by hip-hop. In fact, the interaction between Jamaican music and hip-hop since the 1980s has been as dynamic as its earlier interactions with jazz, soul, rhythm and blues, and funk.

If those weren’t enough to get any reggae enthusiast reading, take Veal’s conclusion that dub’s “Afro-inflected humanizing, communalizing, and spiritualizing of new forms of sound technology is almost surely its most profound contribution to global popular music” (260). It’s a strong contention and one that Veal largely supports in his detailed study. The best part of the book is no doubt the middle section, which features interview-supported readings of some of dub’s greatest engineers/producers and the recordings they made, accounting for technological, social, and sonic matters. But more on that in a few days, when I post my review (which won’t appear in print, I’m afraid, for about a year).

Sounds interesting! Does it include anything on Dub’s and Dancehall’s interaction with other musical styles in the early 80s?

Depends on what exactly you mean, Birdseed. Veal does discuss, esp in the final chapter, everything from punk to techno dub (Pole, Rhythm&Sound) to UK dub/reggae (Jah Shaka, Mad Professor) and various stuff happening in NY (Wackies, Laswell, Spooky), albeit much more briefly than his discussion of dub proper (i.e., the music produced in JA in the 60s&70s). I wish his discussion of dancehall, as well as these other offshoots, was more extensive, but you’ve gotta draw the lines somewhere.

w-

this book looks really great. two quick ?s.

1) how much is discussed on the technological aspect of dub production and Jamaican production in general? there seems to be a reference to more nerdy bits in one of your quotes and I’m wondering how it’s treated in the text. I kinda always introduce dub as the ‘original remixing’, which tends to surprise a lot of people. i need to read this book

2) are there any other good books focusing on dub? what about on reggae in general? suggestions?

-g

Id like to see some examination of why the JA audience “lost interest” in dub…if thats indeed what happened. That seems to be one part of the past that is almost never “revived” in JA.

Good question, Pete, and that story — of how “the” JA audience lost interest — still seems like one of the bigger unexamined myths in reggae. I’m afraid Veal doesn’t really provide much illumination along those lines. On the one hand, I kinda wonder how popular (pure) dub ever was, as opposed to dub techniques, which have long been both popular and thoroughly integrated into reggae. It seems plausible enough to argue that dub was simply (re)absorbed into reggae production, with the real heavy dub stuff — dub for dub’s sake — resigned to being a subgenre of sorts, as any such narrow focus would be, perhaps.

You remind me, tho, that when I was living in JA in 2003, Lee Perry beat Bounty Killer for that year’s Grammy. Callers-in to the local radio programs were pretty incensed, and some were quite confused. I remember one youth complaining that Bounty should have won but instead they decided to give the award to “some madman.” It seemed clear that several people had never really even heard of Scratch.

As for your questions, Giessel, the book actually does discuss the technological aspects of both dub and reggae in rather extensive detail. Plenty of “nerdy bits” in that way, as you say. I think you’d definitely dig the chapters on individual engineers and their tricks and tools, and Veal does make a pretty good case for understanding dub as foundational for the “remix” — an idea that’s been bantered about a lot but hasn’t been treated at length yet. I’m surprised that your assertion surprises people. At least in the EDM lit, dub is often a cornerstone, if invoked fairly facilely.

As for other good books on dub, nothing much comes to mind. David Katz wrote an entire book on Perry (People Funny Boy), and his oral history, Solid Foundation, remains one of my favorite books on reggae (and probably the one that I would recommend most highly). Norman Stolzoff’s Wake the Town is another good book on reggae, if a bit more academic/ethnographic. There’s other stuff scattered around, especially as articles here and there, but I’d start with those two if I were you. (Beth Lesser’s book on Jammy’s is pretty good too — and beautifully designed.)

I’ll have to look those reggae books up – most of the ones I’ve looked through have been heavily biased in favour of roots over ska/rocksteady/dancehall. I’ve got a “litmus test” for reggae books – do they mention Junjo Lawes in a positive light as an incredible innovator, or don’t they get him at all? Most books, unfortunately, are of the latter sort.

That’s not a bad litmus test, Birdseed, and as a great admirer of lots of productions with Junjo’s name on them, I’d have to agree that anyone who dismisses that oeuvre out of hand is worthy of dismissal in their own right. At the same time, I have yet to see a really detailed account of Junjo’s contributions. Clearly, the man had good taste for players and vocalists and engineers, and he had the cash (if dubiously obtained) to fund the sessions, but I really couldn’t say what precisely made him an “incredible innovator” despite his no doubt deeply influential productions.

I think attitudes towards / portrayals of dancehall can serve as a more general litmus test. You’re right that there are lots of roots purists who simply dismiss dancehall as too derivative of gangsta rap or too tied to digital tools, etc. Sometimes they’re quite nasty about it too (Lloyd Bradley comes to mind). Unfortunately, I’ve seen very few accounts that are able to bridge the roots-dancehall divide. Katz does ok, though his focus is really on the period of the 50s-70s; Stolzoff does a little better in coming up to the present, but his focus is more on the soundclash scene. We could sure use a really rich history and ethnography of reggae that begins with Sleng Teng rather than ending there. Soon come?

Yes I wonder how many of the plethora of Dub LPs of the 70s and early 80s sold well in JA?

here here. i’ve been thinking that there should be a little somethin’ that heralds the sleng teng as a not so much a deathknell as a new beginning. i wrote an essay about that once…

Clearly, the man had good taste for players and vocalists and engineers, and he had the cash (if dubiously obtained) to fund the sessions, but I really couldn’t say what precisely made him an “incredible innovator†despite his no doubt deeply influential productions.

This is my take (bearing in mind that the seventies in reggae aren’t exactly my strongest period of knowledge, please someone correct me if I’m wrong):

One of the absolutely strongest trends in popular music for the past forty-something years has been the anti-harmonic one, which involves the replacement of much of western music theory (centering around tonal harmony) with a more rhythmically oriented, supposedly “african” feel.

First to dissapear was most of harmonic progression (starting in the mid sixties and continuing into Funk). However, the chords and triads remained. Also, close harmony, doubled vocals, big orchestras, loads of overdubs etc. etc. were a huge counter-trend in the seventies. The new technology allowed crystal-clear overdubs and loads of channels.

Junjo was, I think, quite possibly the first person in the world with the intent of using the new technology to record as few channels as at all humanly possible, the first perfectly achieving pop music minimalist. His riddims read like a petulant modernist manifesto. No close harmony! No triads! All instruments that play are to be heard at all times! Bass and drums and vocals only for most of the tracks! Transparency! Space! Hygiene!

No-one else in the world was doing this in 1980-ish. Certainly not the other producers (Linval Thompson, Gussie Clarke?) who used the resources of Channel One and the genius of Scientist and the Roots Radics. There are hints towards this kind of total reduction in some early synth material, in underground New York dance acts like ESG and Cavern, in Welsh indie band Young Marble Giants, but all of them sneak in triads or at least arpeggios and none of them go as far as Junjo in reducing harmony and arrangement to clean almost nothing. Or as skillfully maintain musical power, I might add.

I’d say a huge amount of later music owes a debt to Junjo, and I have a hard time imaginging songs like “Lip Gloss” or “Laffy Taffy” existing today without his contributions in the eighties. Or maybe it would have happened anyway, but he was the first to do it. I’d love to have someone prove me wrong and bring me an earlier example.

I see what you’re saying, Birdseed, but I guess I’m not clear on why, say, James Brown wouldn’t be a significant innovator in this right well prior to Junjo. As spare as the arrangements on Junjo’s productions are, the bands are still playing chords and following (albeit simpler and simpler) harmonic progressions. (Peter Manuel and I discuss this briefly in our “Riddim Method” article.)

Moreover, I still remain really fuzzy on what Junjo actually had to do with these aesthetic choices, as opposed to say, the collective effects of the Roots Radics, Scientist, unorthodox vocalists such as Yellowman (who forced engineers like Scientist to remove certain harmonic elements so as not to clash with his odd sense of form), etc. — all of which is to say, I’m not sure how much credit to give Junjo and how much to attribute to the larger collaborative context, including the strong influence of stripped-down American funk on the Radics’ style. I’d love to see an ethnographic/firsthand account of what was happening in those studio and voicing and mixing sessions, who called for what, who made which decisions, etc. Still haven’t come across anything like that in the reggae lit.

Also, although it seems likely — if not exactly corroborated — that the stark dancehall aesthetic of the early 80s had a strong effect on contemporary hip-hop production style, I’m not sure how much credit to give to producers like Junjo, esp once machines like the Roland beat-boxes become popular and all kinds of kids start banging out rhythms with no regard for harmony (a la Schooly D).

Oh Junjo is just a link in the chain all ways, with very significant predecessors, contemporaries and followers, but I think he’s important enough and innovative enough to matter a lot more than someone like Lloyd Bradley would suggest.

I love the Roots Radics, Scientist, the vocalists etc. but I’m still fairly convinced Junjo was the genius. I realise it’s not definite without that evidence but I think a fairly decent substitute is to listen to the material each of the involved parties produced without Junjo’s involvement. Scientist’s dub-oriented solo material, the Roots Radics and Scientist’s work on the huge amount of non-Junjo Channel One dancehall, even Scientist’s 12″ mixes of Junjo’s singles – none of them are anywhere near sounding as consistently and well-adjustedly stripped-down.

Another thing which I would present as evidence if pressed would be the very well-considered progression of Junjo’s best material – assuming he’s the one picking which instrument plays and when, and I think he does. That in a track like “Diseases” he introduces a series of musical effects and then slowly increases the number presented at once, establishes musical ideas and connections using just a couple of well-considered notes or bars, knows when to make his bass dropouts powerful and when to make them smooth etc. etc. shows he’s extremely well aware of his music. Why wouldn’t he be the one behind the main sonic idea too?

Well, anyway, it’s all circumstantial I guess and I’d love to hear more from those involved. Pity Lawes himself is dead.

Hah! Funny that you should mention Bradley. He’s one of the authors I purposely left out of my recommended list above. Not that I didn’t learn anything from Bass Culture (now sold as This Is Reggae Music), which is one of the first books on reggae I read, but having dug in deeper the kind of narrative elisions and value judgments he builds into his telling of “The Story of Jamaica’s Music” (the subtitle) are downright troubling. Junjo is one example, I suppose, but more striking to me are Bradley’s denigration of rap music (and its corrupting influence on reggae, natch) and his assertion, among other things, that the Sleng Teng doesn’t have a bassline (wtf?). Those sorts of distortions totally rub-a-dub me the wrong way, you see me?

Here’s the thing, though: far as I know Junjo never operated a mixing board, and I’m really not even sure how often he was present at the mixing sessions, never mind what his role was. I like the idea of listening to Junjo’s collaborators’ (or day laborers’) other work to try to divine what Junjo did, but I’m not sure what that can really tell us. For one thing, although Scientist’s “solo” authored albums from around the same time seem far less minimal — and indeed can sway toward the maximal — I’m not sure we can deduce from those that he wouldn’t have exercised more restraint, if you will, when working with vocalists for the market place. Do you really know that the mix on “Diseases” is Junjo’s work, or necessarily directly related to his input? I haven’t seen that sort of testimony, and I’ve tried to dig into “Diseases” in some depth. You know, asking Michael Veal this question might not be a bad idea — or any of the musicians still living who were involved in those Volcano sessions.

Even were he alive, I doubt we’d necessarily get a straight answer from Lawes — just try asking Jammy about what role Scientist played on some of the recordings with which they were both involved. That sort of talk can get serious quick.

planning on this one soon soon.

is there not a tension here between the decentralized, multifarious, socially embedded discussion of dub and the lone genius/technologist discussion?

does technology imply more or less expertise? or does it matter what kind of technology? or does it shift expertise from one team to another?

Or does the culture determine whether we get experts or groups/communities regardless of the technology used?

hi wayne. i’m a little wary of posting this, but i did a little mix of the king tubby’s stuff discussed the chapter on him (although i think it is the philip smart dub not tubby’s on the mix):

http://www.dissensus.com/showthread.php?t=6691

enjoying your work form a distance- respect!