![]()

As promised last week, what follows here is my review of Michael Veal’s recently published book on dub. It won’t appear in print for perhaps another year, which is a little silly and unfortunate, but that’s how it goes. I see no reason, at any rate, not to share it now that it’s written, especially if it inspires a few of you out there to pick up the book and read it for yourself.

With regard to book reviews, I should note that every journal is different in their sense of how it should proceed and how long it should be. I far prefer “critical” essays to “book report”-style summaries, natch, though it is usually important, I think, to give prospective readers a sense of what to expect in terms of both form and content. Book reviews are also, of course, opportunities — usually for a “junior” scholar such as myself — to weigh in on a literature with which one is familiar and to flex a little intellectual muscle. Someone like me cares a great deal about the “reggae lit” and how it structures the narratives through which people understand reggae and Jamaica, and so I don’t take this task lightly.

At the same time, I’m a firm believer in generosity when it comes to reviews. Books are the products of years of work and one should never simply shrug that off. Moreover, esp in a small field such as ethnomusicology, one is often reviewing not just the work of one’s colleagues (with whom one should be, well, collegial) but the work of friends. I know Michael and respect his scholarship; he has treated me with kindness and encouraged my own work. I had a nice time chatting with him in Columbus last week, and I hope to lure him up to Cambridge before too long to drop some dubby stuff at Beat Research.

All of that’s to say, especially if Michael ends up reading this (which, he very well might), that critical as I sometimes appear in the review below — and, I should note, it’s always/only in the service of stronger scholarship and sharper language — I’m grateful for the effort Michael has put into his research and this book. I heartily recommend it to anyone wanting to know a LOT more about dub, reggae, Jamaica, Afrodiasporic theory & practice, and, well, making music & meaning in the modern age.

So support a scholar, seen!

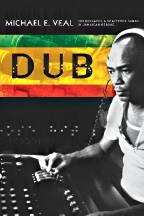

Veal, Michael. Dub: Soundscapes & Shattered Songs in Jamaican Reggae. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2007. 338 pp. Recommended listening appendix, notes, bibliography, index of songs and recordings, index of general subjects. ISBN 0-8195-6572-5.

Michael Veal’s Dub is an informative and welcome contribution to the reggae literature, to studies of Caribbean, Afrodiasporic, and (Afro-)American music and culture more generally, and to the growing field of writings concerned with recording technologies and the social as well as musical dynamics of recording studios (Meintjes 2003, Katz 2004, Green and Porcello 2005). Dub is a multifarious phenomenon: a substyle of reggae; a process and set of procedures for working with musical materials; a network of concepts about authorship, community, and the inner and outer reaches of musical experience and memory. Accordingly, Veal situates dub in deep, rich context, explaining its significance for Jamaican society and Jamaican music and making a strong (if familiar) argument for dub’s impact on music production the world over, in popular and experimental spheres alike. In the process, Veal articulates dub’s symbolic connections to such notions as diaspora and modernity, engaging with the discourses of Afro-futurism and the post-human as well as with postcolonial studies and the emerging literature concerned with sonic or audio culture (Sterne 2002, Bull and Back 2003).

Veal’s attention to both sonic and social matters — and, in particular, their intersections — makes Dub an especially important and distinctive addition to extant writings on reggae, which too often focus on biographical details and record-collector minutiae at the expense of historically and culturally grounded musical-technical exegesis. Although a smattering of articles and chapter-length treatments of dub can be found across the disparate reggae (and electronic music) literature, Veal’s study is the first extended work to approach what he calls the “sonic, procedural, and conceptual aspects” of dub in substantial depth. One way that Veal gets at the myriad intersections of the sonic and the social is through the term soundscape, originally coined by Canadian composer, theorist, and environmentalist, Murray Schafer, to describe the sonic profiles or acoustical environments of the physical spaces we inhabit (see, e.g., Schafer 1977). In what seems like a useful if, to my knowledge, unprecedented (and ultimately confusing) application of Schafer’s term, Veal often uses soundscape as a verb (e.g., posing soundscaping as akin to landscaping). Although Veal’s frequent use of soundscape appears to muddle the term, at least in the sense that Schafer first proposed it and subsequent scholars and theorists have employed it, the (mis)use appears to be an attempt on Veal’s part to show how imbricated songs, sounds, and their social environments often are — not to mention to emphasize the role that engineers and producers play in sculpting sounds and songs. A more explicit discussion of this resignification of Schafer’s term, however, would have made Veal’s innovative application of it far less confusing and also would have strengthened the book’s theoretical framework.

Putting questions of (under)theorization aside for the moment, the crowning achievement of Veal’s study is without a doubt the way he brings to light the distinctive technical-musical efforts and accomplishments of reggae’s most influential producers and engineers, from well-known and heralded producers such as King Tubby, Lee “Scratch” Perry, King Jammy and Scientist to such relatively unsung heroes as Errol Thompson and Sylvan Morris, the longtime engineer at Coxsone Dodd’s groundbreaking, pacesetting Studio One. Moreover, Veal’s emphasis on the people using the technology and the social contexts of such use, rather than on the technology or the music itself, is one of the book’s defining attributes. As the author himself puts it:

All the talk of circuits, knobs, and switches can distract one from the fundamental reality that what these musicians were doing was synthesizing a new popular art form, creating a space where people could come together joyously despite the harshness that surrounded them. They created a music as roughly textured as the physical reality of the place, but with the power to transport their listeners to dancefloor nirvana as well as far reaches of the cultural and political imagination: Africa, outer space, inner space, nature, and political/economic liberation. Nevertheless, this book will focus on those knobs and the people who operated them, in order to develop an understanding of the role of sound technology, sound technicians, and sound aesthetics within the larger cultural and political realities of Jamaica in the 1970s. (13-14)

For Veal the book represents no less than a way of telling, in Jamaican parlance, “the half that never been told” about reggae music.

In order to set up this narrative, the first chapter offers a cogent account of Jamaican musical history, especially the development of reggae and dub. Veal’s concise rehearsal of the half which has been told, if you will, helps to bring the uninitiated reader into the reggae repertory — no small accomplishment considering how vast a musical corpus reggae constitutes and how difficult and overwhelming it can be to delve into and distinguish between the various (sub)styles and historical periods of Jamaican pop. Veal also succeeds in asserting some subtle arguments throughout what otherwise might seem like a recapitulation of well-worn historical-musical transitions. A two page summary of reggae’s twin impulses of internationalization and localization (4-6), for example, manages to place dub at the aesthetic center not just of Jamaican music but of what the author calls “world popular music” and “electronic music” more generally, an assertion he later shores up by linking dub producers to such influential “postwar sound innovators” as Sam Phillips, Les Paul, Tom Dowd, and Teo Macero (37-8), as well as such recent dub devotees as Bill Laswell, Paul Miller (DJ Spooky), and Stefan Betke (Pole). In the course of making such connections, Veal makes strong claims for the significance of Jamaican engineers’ and producers’ aesthetic innovations: “the same musical choices that made local Jamaican music sound so ‘pre-professional’ to mainstream Western ears,” argues Veal, “were simultaneously visionary and deliberate” (6). In a similarly subtle passage, Veal advances a significantly non-essentialist idea of what could constitute “Africa” in the postcolonial, diasporic imagination: “Drum & bass,” writes Veal, referring to a predilection for these instruments and their predominant frequencies and rhythmic roles in reggae, “was thus one of many instances in which musicians of African descent began to deconstruct and Africanize the Western popular song according to whatever ideas prevailed about which musical choices constituted ‘Africa’ in their particular location” (60).

Having situated reggae in Jamaican (and global) social and musical history in the first chapter, Veal turns more specifically to dub in the second. He discusses the roles played by dub plates, “versions,” and DJs in reggae, and he explains the significance of various production techniques (and the technologies through which they are achieved), including reverb and delay, equalization and filtering, tape speed manipulation, the use of microphone “bleed-through” and “nonmusical” sound (e.g., test tones), and the creative “abuse” of equipment (71-77). Veal contends that such techniques help to create and sustain in dub “an aesthetic of surprise and suspense, collapse and incompletion” (77). After thus establishing dub’s technological and musical foundations, Veal devotes the next four chapters — the middle and, indeed, the bulk of the text — to dub’s most important and influential engineers and producers, their idiosyncratic styles and techniques, and their particular contributions to reggae aesthetics. Employing close reading of dozens of recordings, accounting for musical and technical/technological phenomena alike, Veal invites the reader to listen along and engage with dub’s distinctive, and often “disruptive,” musical procedures, from the “disjunct timings” of echoes (72) to the decentering of harmonic form via sudden drop-outs and dissonances (73). Dub producer’ regular disruptions of harmony and form, and the meaning and implications of such procedures, constitutes a central theme in the book. The implications are not inconsequential for those of us who teach in music departments or are concerned with popular music and technology more generally: “The deeper significance here,” writes Veal, “is that this tendency toward a system of harmonic and/or formal resolutions subverted by sound processing would later constitute one of dub’s most transformative contributions to conceptions of form in popular music in the digital age” (73). It is no coincidence that Veal returns to this theme frequently, noting, for example, that Errol Thompson’s dub mixing and the “percussion-dominated” “digital ragga” which built on its foundations, serve to “de-center harmonic practice through the use of polytonality, dissonance, and ‘pure’ noise” (172).

Some of the book’s best moments elucidate issues of Jamaican musical aesthetics while noting the connections to the performance practice of sound systems and the local, physical, social spaces of the dance hall. According to Veal, for example, the concept of “drum and bass,” which serves as the ground (albeit a shifting ground) for the techniques of fragmentation, could be heard as “a new mixing strategy that radically altered the sound of Jamaican music and that arguably established a characteristically Jamaican popular music aesthetic” (59). Advancing an insightful and persuasive interpretation, Veal ties dub’s aesthetics of fragmentation directly to the practice of deejaying (i.e., performing vocals over recordings in the context of a public dance, or later, a recording session):

the process of stripping songs down to their essential components must be understood as substantially intertwined with the practice of deejaying; while studio engineers were beginning to use the mixing board to open songs up from the inside, their work was clearly prefigured by the deejays who destroyed song form from the outside. Rapping, chanting, and shouting their laconic improvisations often irrespective of harmonic or formal changes, and asking their selectors to “pull up” (stop and restart the record) at every opportunity, the deejays were rudely and creatively disrespectful of song form. Ultimately, the aesthetic of fragmented and superimposed vocalizing that would become such an important part of dub music could be thought of as at least partially inspired by the performance style of the sound system DJs and selectors. (56)

Throughout the text Veal reaffirms this connection between dub practice and sound system performance, showing how the music remained grounded in local feedback loops. Quoting producer Philip Smart, Veal reports that, “The test tone, the delay, and rewinding the tape, the crashing of the spring reverb, all of those things we do on the dub [plates] first, so that when them playing against another sound it stand out. That’s where you make your engineering test. Then the producers used them on their songs afterwards” (110).

Given the text’s strengths, it is somewhat disappointing that the final chapters of the book, grounding dub in black cultural studies and exploring dub’s legacy in the wider world of musical production, feel rather tacked on and are far less supported by ethnographic evidence than Veal’s discussion of dub techniques. For years dub has served as a kind of canvas on which various interpreters have painted their theories about Afro-futurism, Afro-sonic modernity, the post-colonial and post-human, to name a few. Although Veal addresses these themes toward the end of the book, the discussion feels as distant as ever from the makers of the music. Veal’s engagement with such theorists as Louis Chude-Sokei, Paul Miller, and Paul Gilroy and such topics as magic realism and postmodernism would have been far more illuminating if brought into dialogic contact with the producers and engineers at the center of the book. Likewise, Veal’s own theories about reverb and echo as diasporic memory, evoking exile and nostalgia, would be a lot more persuasive if supported by the discourse of dub artists and audiences. A more extended, integrated discussion of the “post-human,” for instance, would no doubt have helped affirm Veal’s conclusion that dub’s “Afro-inflected humanizing, communalizing, and spiritualizing of new forms of sound technology is almost surely its most profound contribution to global popular music” (260).

What seems perhaps more problematic in the way of undertheorization, given its prominence in the study, is Veal’s confusing use of the term soundscape, which appears in the title of the book and regularly rears its head throughout the text. Borrowed from Murray Schafer, the term has been a part of ethnomusicological parlance for some time, advanced by seminal studies of acoustic ecology and social structure (Feld 1982, 1996) and employed as a central concept in introductory texts (Shelemay 2000). Veal seems to want to underscore with his use of soundscape the idea that the ambient sounds of a city, a nation, a place are, certainly in the case of dub and reggae, inextricable from the forms and meanings of the songs sculpted in such environs, as in his description of King Tubby’s aesthetics: “What was most provocative was that the cutting edge of sound technology was evolving in what was rapidly becoming one of the world’s roughest and most impoverished areas. Remixing the heaviest riddims crafted by the ghetto’s leading producers, the engineers at King Tubby’s transmuted the tension of daily existence into a style of music clearly emblematic of its social origins” (118).

Applying the term to a single song, however — rather than using, say, songscape or soundspace, which Veal also employs — serves to muddle the clear, singular use of the term as proposed by Schafer and taken up by ethnomusicologists. So when we read that something is “mixed far to the front of the soundscape” (100) or that “Tosh’s voice hovers ominously over a barren soundscape” (146), we lose a sense of how songscapes and soundscapes are distinct, despite their profound intertwinedness. Like other theoretical aspects of the book, the concept of soundscape seems in need of more explicit, clear discussion and integration with the ethnographically-informed readings of dub productions and practices. The closest we get to a development of Veal’s thesis whereby a song’s soundscape relates directly to a place’s soundscape appears in the conclusion (and, interestingly enough, fails to employ the term): referring to John Cage’s Eastern-influenced idea of “purely” “ambient” music, Veal expands, “The idea finds its Afro-inflected parallel in communally driven musics of African descent, where the formal structure of music is often partially predicated on the sounds of the surrounding society and its processes of communal composition” (214).

Despite any shortcomings, Veal’s Dub gives scholars, teachers, and listeners a lot to work with and to build on. Like the influential engineers and producers he profiles, we would do well to take this text and play with it, add and subtract other voices, create our own version. If only Veal and Wesleyan Press would make the master tapes available . . .

Works Cited

Bull, Michael and Les Back, eds. The Auditory Culture Reader. Oxford and New York: Berg Publishers, 2003.

Feld, Steven. Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping, Poetics and Song in Kaluli Expression. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

_______. “Waterfalls of Song: An Acoustemology of Place Resounding in Boasvi, Papua New Guinea.” In Feld, Steven and Keith H. Basso, eds., Senses of Place, 91-135. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, 1996.

Greene, Paul D. and Thomas Porcello, eds. Wired for Sound: Engineering and Technologies in Sonic Cultures. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2005.

Katz, Mark. Capturing Sound: How Technology Has Changed Music. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2004.

Meintjes, Louise. The Sound of Africa!: Making Music Zulu in a South African Studio. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003.

Schafer, Murray. The Tuning of the World: The Soundscape. New York: Random House, 1977.

Shelemay, Kay Kaufman. Soundscapes: Exploring Music in a Changing World. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000.

Sterne, Jonathan. The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002.

Man, I’m really looking forward to getting my hands on this book. Thanks for the review.

Greetings Star,

I love to see a none-Jamaican take up the mantle to project Dub music. I’m looking for a publisher to publish a book on Dance Hall this fall. I also have a Dub CD to be release on the net in mid-July titled: Serious Dub Music Plus. Keep up the good work you have just started to pick at the Jamaican music, check out Producers such as the late Keith Hutson, Cosonxe Dodd, and Harry Moodie Dub vaults.

Yours

Danny Hayles

C/o Talent Express Music & Publisher

27 Florence Dr.

Brampton Ont. Canada L7a 2m2

thanks for the review. got veal’s book at home for some time now, unsure whether it would be helpful for my m.a. thesis on cultural exchange between hip hop and dancehall. now i know i should check it definitely check it out.

by the way, great work that you’re doing!

HIS BOOK IS A MUST!!! It not only features Lee Scratch Perry but Augustus Pablo and Junior Delgado.

A book of photographs by Pogus Caesar celebrating Britain’s iconic black musicians is to be published next month.

The book features evocative, nostalgic and largely unpublished images of musical legends like Stevie Wonder, Grace Jones and Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry.

“These images record a unique period in what would come to be called black British life,” remarks author and historian Paul Gilroy.

“Pogus Caesar’s emphatically analog art is rough and full of insight. He conveys the transition between generations, mentalities and economies.”

Legendary reggae artists figures prominently, and appropriately, in the Caesar image canon – Burning Spear, The Wailers, Augustus Pablo, Rita Marley, Mighty Diamonds, Black Uhuru, Sly Dunbar, Steel Pulse etc. The photographer cites reggae itself is a significant influence, reflecting his own St Kitts background in the Eastern Caribbean.

The launch of Muzika Kinda Sweet follows an exhibition of the work at the Oom Gallery in Birmingham earlier this year.

http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/features/pogus-caesars-muzika-kinda-sweet-2080071.html?action=Gallery&ino=3

A recommended read is this publication. Photographer and film-maker Pogus Caesar eschews hi-tech gear in favour of capturing musical history on an old 35mm Canon Autofocus camera = the results are plain to see, grainy black and white, some images you have to really stare at, then it becomes clear.

Highlights of Muzik Kinda Sweet are the late soul maestro Lynden David Hall and reggae giants Mighty Diamonds, Jimmy Cliff and the legendary Burning Spear.

About time for the book!