I was delighted to get an email last week from a former student, Sophie Weiner, who was working on a piece for the Village Voice about the Brooklyn Folk Festival. She contacted me because she was seeking a quotation about why rap could be considered a form or modern folk music, and she thought, rightly, that I might have a considered opinion on the matter.

I was doubly delighted by this question. You see, this question is practically a word-for-word restatement of discussion question in the History of Rock Class I’ve been teaching at Berklee. Over several semesters, I’ve come to understand some interesting things about the contours of the responses the question elicits. So I was happy to field it.

Here’s what I told Sophie —

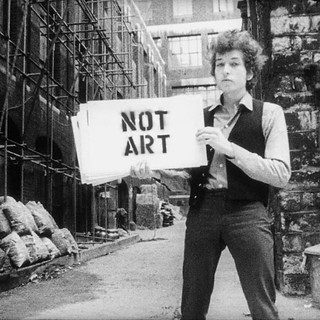

Our class discussion is stimulated by a quotation from Pete Seeger who once argued that “folk magazines make a mistake not to print the best new rap songs.” Notably, although Seeger is really talking about folk music as process, when discussing this question many of my students get hung up on the question of style: “folk” is such a received category for them, if someone’s not singing along to an acoustic instrument, it couldn’t possibly be folk music. This is an association cemented in the 1960s by the folk revival — a movement in which, ironically, Seeger played a major role. Others get caught up by the commercial aspects of rap, though Bob Dylan was no less commercial, of course, and a lot of the songs Seeger popularized as folk anthems were initially commercial products, not simply unattributed ditties roaming the wilderness. Finally, some hesitate to think of rap as modern folk music because so many rap songs don’t seem to share the “progressive” messages that we’ve come to associate with folk, even though many rap songs do offer serious social critiques (if not always in such obviously recognizable form as “Blowing in the Wind”). If, however, we’re talking about a question of process — of collective recitation, reshaping, and recirculation of songs and lyrics — then yes, of course, we could consider rap a modern form of folk music. (That said, we’d have to say the same for other genres of popular music). The best contemporary example in this sense, especially if we’re going with a certain romanticized ideal, would be Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright,” which, like many a Seeger anthem, has become not just a general expressive resource for everyday folk but an actual protest chant.

Of course, this was much more than Sophie was asking for, but I couldn’t say less. I did, however, give her free reign in deciding what to use. (What are blogs for if not “director’s cuts”?) Not surprisingly, in the actual article, given that I am making — ahem — an academic point, Sophie focuses on the resonant connections between rap and folk:

Today, young activists are choosing as their anthems not traditional spirituals but songs by artists such as Kendrick Lamar. Wayne Marshall, an ethnomusicologist and assistant professor of music history at Berklee College of Music, says there are clear parallels between folk and rap. “If we’re talking about [the] process — collective recitation, reshaping, recirculation of songs and lyrics — then yes, of course rap is a modern form of folk music,” he says. Marshall also sees a continuity between the progressive themes of traditional folk music and hip-hop today. “Kendrick Lamar’s ‘Alright,’ like many a Pete Seeger anthem, has become not just a general expressive resource for everyday folk but an actual protest chant,” he says, referencing the multiple instances in which activists have sung the chorus at marches and actions.

Read the rest, for folk’s sake.