Some readers might remember that I participated in a panel about ego trip’s White Rapper Show earlier this year at the annual meeting of IASPM-US. I’ve been wanting to share my thoughts / comments from that session here for a while, but haven’t had a moment to collect (or transcribe) them. Well, I just spent a couple hours this afternoon doing just that. If all goes well, the whole conversation will eventually be published in a print journal (quaint, I know), but since most readers here will never see that, I’m putting it up here too. I’m curious, as always, to hear what other people think, so, you know, holla back.

I mean, I’m saying, your man John Brown did (after a bit of self-googling) —

28 April 2007

IASPM-US

Northeastern University

White Rapper Panel

Wayne Marshall’s comments:

As, at various points in my life, a quote-unquote “white rapper,” I’ve paid a lot of attention to the strategies of white rappers. So one of the most striking things to me about this show was, as some have already touched on, the remarkable range of strategies employed. The contestants have been described here as stereotypes, and that’s true. It seems like they were chosen less because of their skills or their acquaintance with hip-hop culture or their ideas about race than because they could fit this set of types. Learning that G-Child modeled herself on Vanilla Ice — to find yourself in an era where you have people who grew up with Vanilla Ice as their model — says some interesting things about where hip-hop is at today, and perhaps also speaks to the point where we’re at such that Justin Timberlake could be the “King of R&B.”

I was pretty struck by the tension that that also spoke to, the underlying tension in the show. You’ve got MC Serch who, certainly when I was coming up, represented something of a beacon for the white rappers out there. He came out in the late 80s, post-Beastie Boys. The Beastie Boys had already established that white guys could rap, so to speak, and that there were ways of entering into that space, but they did so in a very idiosyncratic and iconoclastic way and a way that drew on their rock side and the general mixed-up-ness of New York culture. 3rd Bass were a significant group because they came out doing more of what seemed like a hardcore, grounded thing; it seemed like more of a community thing, they played at black clubs in New York, they rolled with a multiracial crew, they were very — actually, Serch especially — less so than his partner, Prime Minister Pete Nice, who now apparently has a nice career in Cooperstown selling baseball memorabilia — MC Serch put forward the image of the self-knowing, half-guilty white rapper, a self-effacing position: Look, I understand that I’m implicated in a lot of this white power / white privilege crap and I’m gonna do my best to chant it down in this tongue that I’ve learned. And so he would come out with lyrics like: “Black cat is bad luck, bad guys wear black, / Musta been a white guy who started all that.” So you hear something like that and, you know, me and my friends growing up, we’d all cringe a little bit, like, yeah, musta been a white guy. But you also find a way of negotiating a position there, and that seemed significant.

And something important changed for white rappers not just with Vanilla Ice and the kind of commercialization of hip-hop where it all seems like a big play and performance, but also with the rise of such groups as House of Pain who adopted a very different position, a kind of self-essentializing, strategic essentializing, ethnification of whiteness — in their case, Irishness. It later morphed into what we see in the show when Detroit is portrayed as the “Mecca of White Hip-hop,†which is not what I would, I mean, it’s a weird way of describing it, but certainly it says that today for a lot of kids Detroit is the Mecca of White Hip-hop. It’s where Eminem, Kid Rock, and Insane Clown Posse, who the producers oddly decided also to canonize in this way, are from. And so now we’ve got this white trash essentialism, this class-based position. Fat Joe speaks to this when he appears in a later episode and advises, “Let em know that you’re white but not rich.” And I don’t think that’s necessarily true (i.e., that they’re not rich). But it’s interesting that we get to this point in the white cultural politics of hip-hop that there are these ways of staking out a position that also seem to reify race and seem to make whiteness into something that people claim in a way that is often a little too proud and very different from what Serch used to do with his more self-effacing tack.

And I think part of the tension is that Serch and the Ego Trip guys themselves are upholding this idea of hip-hop that is very much an “old school” / “true school” idea of hip-hop that was really forged in the 80s and came to a certain apogee in the late 80s / early 90s when you had strong Afrocentric politics but you also had a playfulness about it, and it seemed like hip-hop was well aligned with a kind of progressive racial politics. Today it’s not so easy to make that pronouncement about hip-hop. Hip-hop has embraced the hyper-capitalist, pragmatic, hustler stance: I’m just gonna do my thing, I’m gonna get mine, I’m gonna get my hustle on. And that has opened up space for the John Browns of the world who similarly want to position themselves as savvy / idiot-savant hustlers who are just sort of, you know, playing the game.

[Kyra Gaunt asks me to explain who John Brown is.]

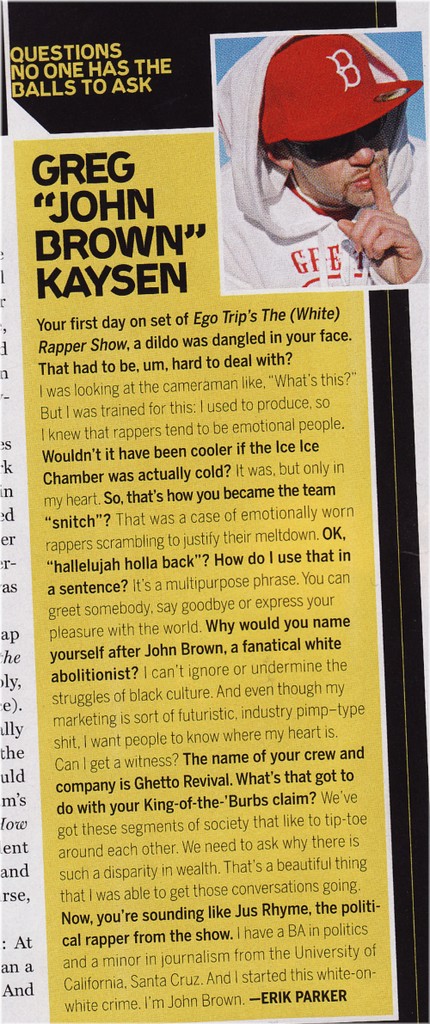

Right, so, John Brown, “King of the Burbs,” “Hallelujah Holla Back.” Those are his big phrases. He represents himself as coming from Santa Cruz, but he lives in Williamsburg. [Someone interjects: He says “Brooklyn.”] Does he say “Brooklyn”? And there’s this great moment later in the show when he’s visited by a friend of his, and his friend is so Williamsburg in a very different way and John Brown’s kind of embarrassed by it. It’s totally undercutting his act.

[Someone asks that I elaborate on the distinction between Williamsburg and Brooklyn more broadly.]

So, Williamsburg is identified these days as a hipster enclave, and it’s been gentrified in lots of ways, and it’s a place where lots of different kinds of whiteness are performed and enacted and a lot of them have to do with signifying on blackness in some pretty weird ways.

[Someone mentions the “Kill Whitey” parties that garnered national media attention a couple years ago.]

The “Kill Whitey” parties, on the one hand they seem to signify a kind of self-awareness, and on the other hand it’s a weird kind of celebration.

[Further comments among the audience about the blackness and Caribbeanness of other parts of Brooklyn and the segregation across the borough.]

So you end up in this funny situation so that in Williamsburg you can go to clubs that are populated by “hip,” white twenty-somethings who don the various trappings of pop culture blackness and listen to popular music by African-Americans, and I’ve heard stories from DJs who are playing at one of these clubs and they put on some reggaeton and the club owner says, “Please take that off, or we’re gonna have all kinds of other people coming in here.” So there’s some really insidious stuff happening there. And that’s partly what John Brown is representing, and yet he’s also very much representing the Harlem, Dipset, mixtape, savvy self-presentation sort-of-thing. They’ve opened up this space for him to get in, and he’s got these slogans like “King of the Burbs” and “Hallelujah Holla Back” and “Ghetto Revival,” which ends up getting him in some very hot water, which I want to get back to in a second. But, I think this gets at this tension in the show where, in some ways, there’s a disconnect between the producers’ values and, basically, market values with regard to hip-hop, and it raises the question: Has hip-hop become so cynical in its own rush to capitalize that it no longer is grounded in a politics of confronting social inequality and racism?

And so, when we see black women stripping to these guys’ “club bangers,” that just puts it in your face in a way that’s really uncomfortable. And one of the better uncomfortable moments in the series is when Brand Nubian is invited to talk to these guys and offer them advice about recording, to “give them jewels,” as Lord Jamar says. So Sadat X starts giving them pretty good advice about mic position and placement and that sort of thing, and Lord Jamar is just looking at them and you can see that he’s pissed off. It comes out later that they had set him up and told him about the whole “Ghetto Revival” thing. So he asks the contestants, “Who’s this with the ‘Ghetto Revival’ thing? What’s that about?” And John Brown says, “It’s a revival.” “Of what,” says Jamar. “Of the Ghetto.” [Laughter] And Jamar says, “The ghetto is poverty and pain, mostly for black people.” He just puts it right to him like that, and John Brown just says “Hallelujah Holla Back.” And he’s just a cipher. He just repeats these phrases, and that’s his strategy. He plays this kind of idiot savant. And the argument that I want to get to in a minute is, well, I’ll get to it in a minute.

But one interesting thing that gets us toward it, is that when Serch is introducing Brand Nubian, he says, “This is where the culture is.” Right? And, I mean, who are we kidding? Half of the contestants didn’t even know who Brand Nubian was. Sure, for people like Serch and Ego Trip and those of us in this room who came up on hip-hop in a certain moment of time, that is what it was about, where it was at. It was about a certain militant racial politics. And we can see what Serch means by that. But he’s totally kidding himself if he’s saying that at this point. So again that gets down to this central tension in the show where they’re trying to wrest control of the meaning of hip-hop and therefore its critique of race. But it has gotten out of control.

To come to a little conclusion here, this tension can best be encapsulated in the idea of the “game.” We hear all the time from rappers that they”re playing this “game.” Don’t hate the player, hate the game. And that gets put to the test here. In the final episode, when John Brown is about to go against Shamrock — who is a genuine-seeming guy from the Atlanta area, grew up in a multiracial environment, and just seems very sincere about being a rapper in a traditional mode, if in a down-South party style, which has its own weird politics — John Brown tells the camera, “I think I’m the best look for the game.” That’s his statement, and I think it speaks volumes about that tension there. And yet, at a certain point, Chairman Mao, one of the Ego Trip guys, says, “It’s all a ruse. There is no correct answer. It’s playing with stereotypes.” Which also seems to suggest this kind of play, this kind of game. And yet what does MC Serch keep repeating throughout the show? “THIS IS NOT A GAME!” Every time he comes into the house, he says it: “This is not a game, people!” And yet, what is it? It’s a game show! They’re competing in challenges! Every episode, they’re playing a game. It’s a game show.

In the end, Elliot [Wilson] from Ego Trip says, “The good guy wins.” And so they did pick the guy they wanted to win. They picked Shamrock. They picked the genuine guy who seems to maybe have some tenuous connection to this ideal of hip-hop that they’re holding up. But if they were more cynical and if they wanted to talk about where hip-hop really is right now, they would have picked John Brown.

I was only vaguely aware that something called “The White Rapper Show” existed, but nonetheless, I got a lot out of your thoughts here. Thanks for writing.

IK

“Has hip-hop become so cynical in its own rush to capitalize that it no longer is grounded in a politics of confronting social inequality and racism?”

Alot of hip-hop circa 79 to the early 80s was not grounded in a politics of confronting social inequality and racism. If I am reading that sentence right it appears that you’re trying to inject your own political take as much as the Ego Trip folks.

I think you’re reading that sentence right, but you’re taking it out of context. By no means am I trying to imply that hip-hop has always been, at least until recently, essentially about “confronting social inequality and racism.” Indeed, I really try to be vigilant about such anachronistic readings of hip-hop history, projecting into the past our own ideals and “political takes,” as you put it.

As you imply (without offering much evidence), prior to “The Message” (1982), so-called “socially conscious” hip-hop tracks were rather rare, and the genre could hardly be said to be “grounded” in that sort of “politics.” What I’m referring to, however, is the turn that hip-hop took in the late 80s and early 90s, when a great deal of what was being made — even on the gangsta side of things — was very much concerned with the effects of poverty and racism. That’s the era during which the figure of “the white rapper” — for EgoTrip and Serch and, yes, for me too — was largely shaped. (Name me a white rapper from “79 to the early 80s.” I’d love to know what sort of strategies they were employing back then.)

It’s not about “injecting” a “political take” so much as offering a (hopeful) reading of hip-hop as a powerful agent of social change. For those of us who grew up with the music during its so-called “Golden Age” (even if that came along with gold chains and other forms of conspicuous materialism), we naturally feel that something has been lost in an era when the hustler ethos — an individualistic, pragmatic, and often apolitical stance — reigns supreme over more communitarian commitments. But that’s just one reading, of course, and it appears to be a rather unpopular reading at that.

my fave white rapper is mc900ft jesus what happened to him?