This mix amplifies the resonances between the music of 19th century composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk and the bedrock rhythm of reggaeton and a great deal of recent pop music — a/k/a, dembow. As much a tribute to Gottschalk’s faithful fantasias as to the numerous architects of dembow aesthetics, we hear in their juxtaposition how one particular Afrodiasporic beat has served as foundation for social music and dance across the Americas and across time. While it is tempting to interpret the recent ascent of dembow and other 3+3+2 “electronic tresillo” rhythms as part of a new wave of Afro-Caribbean influence on pop and club music, Gottschalk’s parlor proto-dembow of the mid-19th-century reveals this recent prominence as less a sea change than an old tide washing ashore once more — and, moreover, that the US is no exception in this pan-American history, no island unto itself.

This mix may be a novel confection, but the music here is more than a BRAND NEWWW NOW TING. It’s an ancestral wellspring. Not ¡NUEVA VAINA! but ¡ANTIGUA VAINA! — an ancient thing. Get hip already–

w&w, Louis Dembeau Gottschalk (¡Antigua Vaina!) [MP3 13:46 31mb]

tracklist:

Bamboula: Danse des Negres, Op. 2 (1849)

The Banjo (Grotesque Fantasie), Op. 15 (1854)

Ojos Criollos: Danse Cubaine, Op. 37 (1859)

Danza, Op. 33 (1857)

Souvenir de la Havane, Op. 39 (1859)

Souvenir de Porto Rico: Marche des Gibaros, Op. 31 (1860)

b/w “Panameña” (Colon/Lavoe, 1970)

Historical Context

170 years before “Despacito” made the dembow as ubiquitous as ever, an 18-year-old composer and piano virtuoso from New Orleans deployed the same Afro-duple rhythm to score a remarkable international hit of his own. Louis Moreau Gottschalk’s “Bamboula” took the Parisian salon scene by storm, and among others, Chopin sang his praises as the most impressive musician the United States had produced. Subtitled “Danse des Negres,” the composition was inspired by the songs and dances of Place Congo, or Congo Square, a public site where free and enslaved Africans would gather on Sundays to participate in a market and in collective singing and dancing. These gatherings began during French rule and continued for decades under the Spanish before New Orleans became US territory, and Place Congo remained a rare site where African and Afrodiasporic drumming and dancing were permitted even into the Anglo-American era.

Gottschalk’s oeuvre bears early witness to the popularity of certain Afrodiasporic rhythms that have become central to the entire world’s popular dance music. Fifty years before ragtime would popularize “syncopated” dance music and revolutionize the world of popular music and publishing, and 150 years before dancehall’s and reggaeton’s global pop insurgence, Gottschalk’s representations and “souvenirs” of the folk/dance music of New Orleans, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Haiti, et al., offer a wonderful sort of musical record — before audio recording was possible. In this sense, I’ve been using Gottschalk’s music in my classes to discuss the epistemological issues associated with recovering the musical past, and I like to compare him with the likes of Lomax, Gershwin, perhaps even a Diplo — as well as to Dvorak, Chopin, or Ellington for that matter.

His efforts were certainly received among his publics and contemporaries as of-a-piece with other attempts to use folk sources as the basis for art music. In some way, a composition like Bamboula is as close as we can get to hearing Congo Square — or at least echoes of the songs and rhythms that animated the dances there. The question of what Congo Square sounded like is what Ned Sublette, in The World That Made New Orleans, calls “the city’s great musical riddle” (121). It was in Sublette’s work, in fact, where I first began to learn about the significance of Gottschalk to American musical history (i.e., American in the broadest sense — not, as I joke with my students, the “greatest” sense). Incidentally, Sublette specifically invokes Gottschalk to discuss this great riddle. Allow me to quote Ned’s punchy prose at some length:

Congo Square occupies a central place in the popular memory and imagination of New Orleans. At the core of it is the city’s greatest musical riddle: what did it sound like? Since we don’t have recordings, we don’t exactly know. But we have some knowledge of the instruments that were played at Congo Square.

And I think I have a pretty good idea of at least one rhythm that was played there.

… It’s a simple figure that can generate a thousand dances all by itself, depending on what drums, registers, pitches, or tense rests you assign to which of the notes, what tempo you play it, and how much you polyrhythmacize it by laying other, compatible rhythmic figures on top of it. It’s the rhythm of the aria Bizet wrote for the cigarette-rolling Carmen to sing (though he lifted the melody from Basque composer Sebastián Yradier), and it’s the defining rhythm of reggaetón. You can hear it in the contemporary music of Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Puerto Rico, to say nothing of the nineteenth-century Cuban contradanza. It’s Jelly Roll Morton’s oft-cited “Spanish tinge,” it’s the accompaniment figure to W.C. Handy’s “St. Louis Blues,” and you’ll hear it from brass bands at a second line in New Orleans today. At half speed, with timpani or drum set, it was a signature rhythm of the Brill Building songwriters, and it was the basic template of clean-studio 1980s corporate rock. You could write it as a dotted eighth, sixteenth, and two eighths. If you don’t know what I’m talking about yet, it’s the rhythm of the first four notes of the Dragnet theme. DOMM, DA DOM DOM.

It’s the rhythm the right hand repeats throughout “La Bamboula (Danse des Negres),” Op. 2, a piano piece composed in 1848 to international acclaim by the eighteen-year-old Domingan-descended New Orleanian piano prodigy Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1830-70). A stellar concert attraction of his time, and, in this writer’s opinion, the most important nineteenth-century U.S. composer, Gottschalk’s legacy is inexplicably neglected today in his home country. As a toddler, he lived briefly on Rampart Streetm about a half mile down from Congo Square, at a time when the dances were still active, and he would have, like other New Orleanians in the old part of town, been familiar with the sound of the square. Some have suggested that Gottschalk was not trying to evoke the sound of Congo Square literally in the piece. But I think Gottschalk was telling us something: when they danced the bamboula at Congo Square, they repeated that rhythm over and over, the way Gottschalk’s piano piece does, the way reggaetón does today–and over that rhythm, they sang songs everyone knew.

Frederick Starr identifies the basis for the main theme of Gottschalk’s “Bamboula” as a popular song of old Saint-Domingue, “Quan’ patate la cuite,” which Gottschalk learned from Sally, his black Domingan governess. Was Gottschalk, a programmatic composer, drawing a sound portrait of a dance at Congo Square? And might he be inadvertently telling us that the singing, drumming, and dancing circles put popular melodies into their own rhythms and style? (121-125)

Sounds a lot like reggaeton, dembow, and dancehall to me! And not just in conceptual terms — i.e., invoking familiar melodies over cherished rhythms. What is especially striking is that the rhythmic figures in question are, in essence, one and the same: that ol’ 3+3+2, especially in the form of a tresillo (A) or habanera / tango pattern (B) and/or as the slightly embellished, 5-strike form (C) that became a signature rhythm in ragtime (and appears in so many other styles since, including as a common 4th or 8th measure turnaround in reggaeton productions).

A: ![]()

B: ![]()

C: ![]()

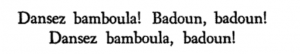

Indeed, the words that may have underpin “Bamboula” as a Place Congo chant themselves appear to engender this 5-strike rhythm:

The word bamboula here, notably, sits at the crux of the dembow rhythm. You could imagine J Balvin saying it instead of “Beyoncé” or “C’est comme-ci … c’est comme-ça” or Wyclef subbing it in for “Bonita … Mi Casa” or Lionel Richie putting it in place of “Fiesta … Forever.” In other words, this figure’s been around, still underpins so much, and as such offers a wonderful way to counterpose seemingly disparate songs and styles.

And that’s how we arrive at this mix, at least conceptually. The technical aspects are another concern entirely. I’ll offer some discussion of those dimensions below for anyone who’d care to read further.

Technical Notes and General Poetics

I’ve sought to bring these two bodies of work — Gottschalk and dembow — together on each other’s terms as much as possible, honoring at once (while also inevitably violating) the aesthetic priorities of programmatic classical and reggae/ton.

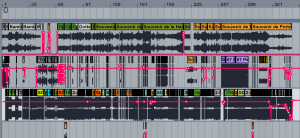

Let’s talk about the violations first: in order to match up Gottschalk’s music with dembow loops, I have had to remove nearly all of the rubato elements — i.e., expressive tempo dynamics — from the performances of his work. I suppose I could have attempted to impose rubato effects on the drum loops, but I actually believe that the grooves that inspired Gottschalk were unlikely to feature as many timing variations as he builds into his compositions and his modern interpreters bring to bear on them — correctly so, given that many of these pieces invite such a capriccio treatment, leaving timing decisions to the whims of the performer. So I decided to “flatten” out this aspect of Gottschalk’s music, turning elastic tempos into entraining, locked-in dance grooves. (I also shifted the various tempi of his compositions so they all roll along at a rather reggaetony 100bpm.) This, of course, required meticulous, Ableton-abetted “warping” at the level of nearly every measure (and sometimes every beat), and it probably took up the largest chunk of time of any of the procedures involved in the production of this mix.

I have also, rather than honoring the full integrity of his composition, employed selective fragments of Gottschalk’s works — namely, the parts of his compositions that feature tresillo-style figures. This “sampling” strategy seems, to me, consistent both with reggae/ton practice and with Gottschalk’s own tendency toward a certain level of pastiche, quotation, and recontextualization.

Moreover, the drums here — that is, the dembow loops (including two of the most common “Dem Bow” pistas and a handful of Sly & Robbie loops, many titled “DembowLoop5,” etc.) — are as important and as prominent in the mix as the piano. This is a duet of sorts, and so I am necessarily bringing a strong reggae/ton presence to the proceedings, including the use of airhorns, sirens, winking samples, and other classic mixtape / DJ drops, as well as drums that punch aggressively through the texture.

On the other hand, I have attempted to honor and employ some of the affordances of classical music in the mix, and this includes manipulations of the dembow drum loops. For one, I have attempted to be mirror some of the intensity dynamics in Gottschalk’s music by lowering and raising the volume of the drums at appropriate times. More radically, I have chopped, layered, and rearranged the various drum loops to the point where they closely match and complement the rhythms of Gottschalk’s pieces. The drums in this mix sometimes sound less like loops than through-composed elements. In this sense, I am frequently following Gottschalk’s lead, even as I submit his music to a somewhat quantized groove.

While Gottschalk’s rhythmic vitality is what I’m mainly looking to harness and highlight here, the degree of melodic variation and harmonic transformation in his music offers a refreshing contrast to the more repetitive melodies and reduced harmonic structures of reggae and reggaeton. Notably, and usefully, Gottschalk often builds these variations in a manner that mirrors the additive and subtractive layering in a reggaeton track. This provides an opportunity to underscore, beyond their Afro-duple rhythms, other things these genres have in common despite the fair distance between them in terms of time and aesthetics.

Gottschalk’s works and reggaeton productions both tend toward clear demarcations of regular, sectional development. In reggaeton, this has tended to be marked with shifting snare samples, reflecting an earlier practice of swapping out favorite loops during maratón rap sessions. In the classical forms Gottschalk was working in — if often such permissive / vague forms as fantasie or caprice — we hear this approach more in terms of sectional melodic variation and harmonic development. Together in the mix, these parallels work strikingly well — as well, I think (and hope), as the fundamental rhythmic overlap that inspired this entire exercise.

Implications and Reflections

Formally speaking, Gottschalk favored fantasies and caprices, especially for his lively piano pieces, and I myself have made some capricious choices that I hope are in the spirit (both of Gottschalk and of reggae/ton). One of these involves bringing in an excerpt of Willie Colon’s and Hector Lavoe’s “Panameña” toward the end of the mix — a decision that posed substantial technical / aesthetic difficulties. (Because each piece takes a slightly different approach to re-harmonizing the song, I’ve settled on a slightly sour, “woozy chipmunk” attempt to make them mostly line up.)

Even though “Panameña” is in a different key than Gottschalk’s Souvenir de Porto Rico, I couldn’t resist putting them together as both cite the same Puerto Rican folk song, an aguinaldo often sung as “Si Me Dan Pasteles.” The reference appears in the montuno section of “Panameña” where it serves as a potent invocation of Puerto Rican identity amidst a broader message of pan-Latinidad. As Lavoe sings,

yo canto guajira

yo canto danzónle canto un bolero

canto un guaguancópero no me olvido

del aguinaldo

pero nunca olvido

el aguinaldo

The sonero’s sentiments are affirmed as the chorus responds with a distinctively Boricua refrain, “lo le lo lay” — honoring Puerto Rican musical forms alongside the Cuban and pan-Latin forms that Lavoe cites.

One thing that I hope my mix does, which is one thing that I believe Gottschalk’s music does, is to extend this idea of the deep, audible, palpable connectedness of the Caribbean and Latin America — of the diaspora and the creolized New World — so that it also includes the United States, not as an outlier or an exception but as one node among many in a network, at once a source and a destination, a distinctive set of social and cultural contexts which are, nonetheless, enmeshed in hemispheric and trans-Atlantic connections.

Among other things, this mix is, then, a proposal that we hear the US’s own Afrodiasporic heritage as alongside and inextricable rather than exceptional — and inextricable because of the echoing legacies that are a consequence of slavery and the creole societies that follow in the wake.

This is, finally, simply, a souvenir, of Moreau and dembow both — for me and for anyone else with whom it resonates as something to think, sing, or even dance along with.