I’ve got an article in The Wire‘s new issue devoted to “Freedom Principles” (December 2014). I was inspired by the call for submissions to thread the idea of freedom through the story of Dutch bubbling, which I think embodies it in a number of important ways.

After having the privilege to visit with some of bubbling’s pioneers and torchbearers in Aruba this September, I’m feeling as inspired — and required — as ever to give this wonderful story of translocal music culture and creativity the telling it deserves. This is a start.

I’ve also put together a “portal” of audio and video examples for the Wire’s site; check it out and sink deep into the sounds and images of bubbling!

http://www.thewire.co.uk/in-writing/the-portal/dutch-bubbling-portal

The essay that appears in the print issue follows below. Big up Moortje, Chuckie, Coversquad, Fellow, & everyone else involved in this remarkable story! Thanks for sharing with me. Keep bubbling free!

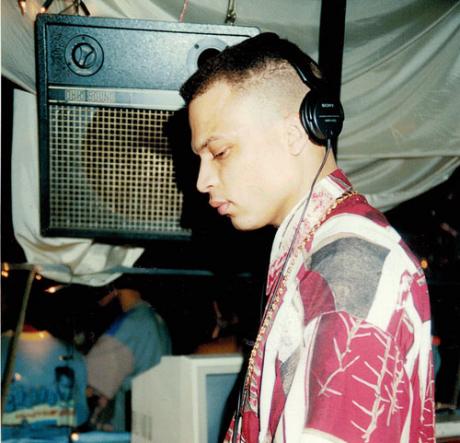

Moortje on the decks in ~92

Is there any sound so free as DJ Moortje’s mid-1990s track “Donna”, his remix of Singing Sweet’s 1992 lovers rock rendition of Richie Valens’s 1959 hit pitched to chipmunk levels and propelled by doubled-up dancehall drums in double time? With such feathers in its cap, Dutch bubbling should have long ago established the Netherlands on the global bass map. A hyperkinetic, hyperlocal, sample-centric take on dancehall, bubbling thrived in obscurity throughout the 1990s, and today it continues to enjoy a certain liberty on the margins of international reggae culture. Obscurity is but one of several key forms of freedom embodied by its almost implausible existence. Its very genesis and gestation, never mind its spectacular and strange shapes, are products of the buttressing effects of inherited traditions with liberating aesthetics, technologies with plasticity, and the social support and political economy of small scenes.

Networking Holland’s immigrant enclaves in Rotterdam, Amsterdam and the Hague, bubbling took root in dancehalls where African-Antillean youth could gather, socialise and dance. Notably, the music of choice for first and second generation migrants from Aruba, Curacao and Suriname was supplied not by these islands or the Netherlands, but by Jamaica. At clubs such as Voltage in the Hague or Imperium in Rotterdam, dancehall reggae provided a soundtrack for couples to rub-a-dub, schuren (that’s Dutch for rub), or, in the parlance of the day, bubble along with sensuous, polyrhythmic Jamaican music that sounded at once Caribbean and global, ancestral and utterly modern. Bubbling — or bobbeling — channelled the energies of a new youth culture that gave people united by their experience in postcolonial Dutch society a common platform for creativity and community, especially as DJs and dancers together pushed tempos beyond reggae’s comfort zone and twisted dancehall into a shape that became more recognisable as a local innovation.

Bubbling’s DJs, MCs, producers and dancers took flight from reggae’s DJ driven and remix-oriented music culture, an imperative to revisit and revise familiar forms accentuated by hiphop’s relentless flipping of scripts. Inspired at once by hiphop sampling and reggae versioning, the practitioners of Dutch bubbling remade dancehall in their own image, manipulating samples of well-worn riddims in ways no Jamaican producers ever would. In this way, bubbling’s referential yet irreverent chop and stab approach to dancehall — more directly derivative than a reggae relick but less faithful to a riddim’s integrity — makes it an uncanny twin of reggaeton; they even share a love for the same canon of riddims: “Fever Pitch”, “Bam Bam”, “Dem Bow” and pretty much anything featuring Cutty Ranks. With a premium on transformation, skirting the line between recognition and surprise, Dutch-Antillean DJs like the pioneering DJ Moortje would take reggae B side versions and make them the basis for new performances, quite as they were intended — if not in the wildly distorted shapes Moortje and cohorts would make of them. Recording new vocals over an instrumental is one thing; combining loops from multiple riddims, some pitched to double time and some screwed to molasses, spiked with whimsical samples from the hardcore gabber of Rotterdam Termination Source or Snoop Dogg album skits, is another thing entirely.

Moortje enjoyed a critical degree of creative freedom thanks to the affordances of vinyl and turntables. Exploiting the limited but profound capacities of these playback technologies, he took the familiar records that made dancers bubble and pushed their tempos into uncharted territory by playing 33 rpm records at 45 rpm and sliding the pitch fader right up to and beyond its upper limit. Given the opportunity, Moortje would sometimes remove the turntable platter from a pair of Technics to access an internal knob controlling the pitch adjustment range, allowing him to shift 100 bpm riddims into a far more uptempo terrain.

Moortje showing me, in the sand, how he would modify the Technics’ pitch range

Later, audio software vastly expanded bubbling’s creative possibilities. Moortje’s innovative performances planted the seed for speed bubbling, a digital development first enabled by Amiga 500 tracker software that allowed production crews like The Coversquad to take tempos upwards of 150 bpm, much to the bemusement or dismay of visiting reggae artists experiencing bubbling’s love of chipmunked and screwed vocals and drums. Commissioned by dancers requiring dramatic, sample-packed soundtracks for their choreographed, competitive routines, producers would suture audio from films and rap albums onto the breakneck bubbling beats that impelled dancers to move like marionettes doing the butterfly. Indeed, the strikingly experimental nature of bubbling productions was predicated on an intimate feedback loop with audiences who appreciated how the music had coalesced as a genuinely local style. Such a supportive setting was fostered and enjoyed by MCs like Pester and Pret, who helped to push the tempos and excitement levels as they added their own accents to the mix. With their Dutch and Papiamento lyrics chanting down Babylon or simply telling people to shake it, bubbling’s MCs further imbued the music with local resonance.

For better or worse, bubbling’s deeply idiomatic qualities may also grant the genre a certain freedom from external forces. In its heyday, it only happened live or on recordings informally circulated on cassette, meaning its heavy use of samples bypassed the attentions of the mainstream pop industry. Whether mainstream Dutch house has since effectively sublimated bubbling’s mojo is an argument for another day. And even as the music’s artefacts finally mount up in online archives like YouTube and Soundcloud, or as musical references percolating through the releases of Fade To Mind, Mad Decent, or Planet Mu, bubbling’s baseline weirdness might yet guarantee that its signature sound will always be free.

Wayne Marshall