A few things to add to my recent post about graffiti in Mexico City —

First, Said Dokins, one of my guests at Postopolis, writes to share some supplementary materials — in particular, documenting the role played by women in “arte urbano”:

También te mando unos links de los libros que nuestra editorial tiene actualmente sobre arte urbano hecho por mujeres, haber que te parecen, ahí también viene textos míos sobre el arte urbano en México y su relación con problemas de género.

Desbordamientos de una periferia femenina:

http://issuu.com/saidokins/docs/pn_todo

http://proyectopneuma.blogspot.com/

y La calle es de nosotras. La participación de la mujer en el arte urbano:http://issuu.com/saidokins/docs/la-calle-es-de-nosotras-web

http://lacalleesdenosotras.blogspot.com/

And while we’re on the topic of awesome online flip-page book scans (check that first URL above), this is a fine time to share a link to a flippy version of Tomo, the art/architecture/design magazine edited by some of the same DF denizens who were crucial in making the event an event (or a series of them). I’m happy to report that my post on graf en La Ciudad has been translated & excerpted to run in the latest issue of the magazine, devoted to Postopolis DF. Looks sharp!

Click on the picture below to view it flip-book style, or read selected articles right on the Tomo site, including mine.

Finally, I want to append to the discussion another resonant passage about all the writing on the walls in Mexico. This comes from John Ross’s “phantasmagoric” history of Mexico City, El Monstro (p. 145-6):

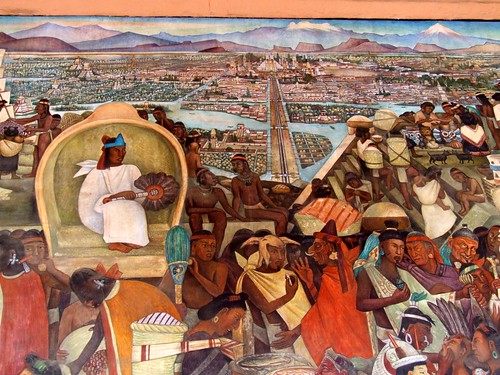

Painting walls was a Mexican art even before the people had a name — ancient caves from one end of the country to the other are enlivened with prehistorical glyphs. The Toltecs embellished the walls of their short-lived empire with painted images of the gods. The Mayas decorated the chamber of their dead emperors with messages to the future. The Aztecs daubed the snake wall that fortified their sacred precinct with fantastic serpents. The messages advertised on these rough canvases often depicted the gods’ predilection for the peoples who had painted them and the peoples’ heroic supremacy over their hapless enemies.

Obregón needed walls to get the message out. He would turn them into billboards for the revolution. José Vasconcelos, his secretary of public education, had those walls.

…

Armed with Obregon’s largesse, the secretary of education contracted a trio of hotshot young muralists to stipple the walls of public buildings with revolutionary icons: Diego Rivera, just back from Paris; the stern and doctrinaire Marxist David Alfaro Siqueiros; and José Clemente Orozco, an explosive visionary. Of the three, Rivera was physically and temperamentally the most prominent. Over six feet tall and close to 300 pounds, with bulging eyes (his beloved Frida referred to him endearingly as mi sapo — my toad), Diego would cast a ham-fisted shadow over Mexican art for half a century.

1 thought on “More Writing on the Walls: Graffiti En DF Addenda”

Comments are closed.