This page hosts audio & visual media to accompany my June 2020 article, “Ragtime Country: Rhythmically Recovering Country’s Black Heritage” (PDF). The essay and mega-mix are my contribution to “Uncharted Country,” a special issue of the Journal of Popular Music Studies that seeks to respond to this remarkable moment of flux and play in the world of country music and, in the words of editors Nadine Hubbs and Francesca Royster, “to amplify its generative potential.” Their call for submissions inspired me to bring into public shape what I believe is a profound story about rhythm and race, one that has drawn me far more deeply into the history of country than I could have imagined. I’d like to thank Dean and Francesca for their support and feedback, Esther Morgan-Ellis for shepherding things to publication, and all the friends and colleagues I’ve consulted along the way. It’s a privilege to be a part of this special issue and to finally share this story.

First things first: the mega-mix!

You can stream (right here, or via Mixcloud or Soundcloud) or download [MP3] the mix in audio form —

— or watch along via video to track the transitions as well as artist names, titles, and dates while you listen. (YouTube link)

American Clave Mega-Mix

While the full mix crossfades — more or less in strict chronology — from ragtime to old time, jump blues to bluegrass, Nashville pop to Detroit techno, some readers/listeners may prefer to focus on particular lineages — e.g., hearing the rhythm jump from ragtime string bands to Western swing bands, country-ragtime guitarists to rockabilly soloists, and into the C&W mainstream and nods from rock bands, without the synchronic (but perhaps distracting) presence of jazz, blues, R&B, and so forth. Although I recommend the holistic approach, I have created a couple “breakout” versions of the mix — mini-mega-mixes, I suppose — to highlight specific stylistic threads: one to plumb the country line; another to trace the rhythm’s presence in rap. (I’m tempted to cook up a disco version too.)

I’m happy to report that the videos are embedded in the article itself. I appreciate the UC Press supporting this approach to scholarship since corporate platforms are so vulnerable to the enclosures of copyright. On this page, I have embedded those videos via Google Drive or YouTube when permissible. See below for the “Country Twang” mix as well as the “Rap Attack” version, ft. Run DMC, 50 Cent, Eminem, Kendrick Lamar, and Cardi B (with a little help from Scott Joplin, Louis Armstrong, and Duke Ellington).

Country Twang Mini-Mix

Rap Attack Mini-Mix

Below I will offer extended thoughts on the mega-mix as representational practice, as well as further rhythmic disambiguation for those who want to get into the weeds. For now, I will leave you with the abstract and a mashup that helps to frame the central tension of this story.

In 1955, Elvis Presley and Ray Charles each stormed the pop charts with songs employing the same propulsive rhythm. Both would soon be hailed as rock’n’roll stars, but today the two songs would likely be described as quintessential examples, respectively, of rockabilly and soul. While seeming by the mid-50s to issue from different cultural universes mapping neatly onto Jim Crow apartheid, their parallel polyrhythms point to a revealing common root: ragtime. Coming to prominence via Maple Leaf Rag (1899) and other ragtime best-sellers, the rhythm in question is exceedingly rare in the Caribbean compared to variations on its triple-duple cousins, such as the Cuban clave. Instead, it offers a distinctive, U.S.-based instantiation of Afrodiasporic aesthetics — one which, for all its remarkable presence across myriad music scenes and eras, has received little attention as an African-American “rhythmic key” that has proven utterly key to the history of American popular music, not least for the sound and story of country. Tracing this particular rhythm reveals how musical figures once clearly heard and marketed as African-American inventions have been absorbed by, foregrounded in, and whitened by country music while they persist in myriad forms of black music in the century since ragtime reigned.

Read the rest, with embedded examples, at JPMS. (Or, if you do not have institutional access, you can find the PDF here, sans examples.)

How We Do: Mega-Mix as Form

When planning this mix, I faced the quandary of how to illuminate particular lines of influence (i.e., diachronic relationships) while also highlighting synchronic simultaneity and shared reference points. I wanted neither to redraw American color lines nor to obscure how ideas about racial difference have informed musical aesthetics and meanings. If Ray Charles and Elvis Presley were both using these rhythms in the same year — and both were heard as rock’n’roll — then of course we should listen to them together; on the other hand, while Charles’s points of reference for the arrangement of “I Got a Woman” were big band swing and small band rhythm & blues, Scotty Moore’s guitar picking points back to Merle Travis and forward to the likes of the Beatles. Communicating all of this in a medium of sequential horizontality — i.e., a continuous mix that unfolds in time and allows only a certain amount of verticality, or overlap — is no easy task.

The mega-mix allows for moments of direct juxtaposition as well as sequential development, and I’ve tried to enlist those aesthetic affordances carefully. I want to acknowledge my debt to all the great DJs who have collectively labored to make the mega-mix the rich vehicle that it is: from such 1980s architects of the form as Double Dee and Steinski or the Latin Rascals, to blog-era efforts like the thematic mixes of my fellows in the Blogariddims crew back in 2006-08, to the likes of Nguzunguzu’s inspiring “Moments in Love” mixtape / Soundcloud drop — a mix focused on a single song / sample-source and its ongoing, transmuting social life — which I continue to use as a model in my technomusicology classes. Drawing audible lines from track to track offers a powerful way to tell stories about musical histories and relationships, and while I’ve made many a mega-mix over the years (including to support scholarship), this is the most mega by far, combining over 170 recordings dating between 1891 and 2020. (Full tracklist below.)

While I’ve borrowed lots of tricks from other DJs and mega-mix makers, in a departure from my previous mixes and from mixtape practice more generally, I’ve taken the poetic license to add some 808 percussion in a follow-the-bouncing-ball (or synth-cowbell!) fashion. I hope this doesn’t distract or detract, or creates too “pedagogical” a vibe, but I want to help some listeners hear the rhythm pop through the texture. Despite the risks (and occasional anachronisms), I quite like the way the 808s provide some sonic glue from old to new, and I couldn’t resist enlisting regular help from similarly sync’d drum breaks and 50 Cent’s iconic American clave chant: “/ This / Is / How / We / Do ”

My selection process has been fairly unscientific on the one hand and somewhat systematic on the other. While I have made attempts to listen carefully for the American clave across various genres and eras for this project, I have collected the majority of my 200+ examples through coincidental, if studious, encounter, especially in the course of prepping and teaching “Music of the African Diaspora in the United States” at Berklee College of Music each semester for the past five years. It was in that context, and while privately trying to learn Maple Leaf Rag on piano, that I began noticing this unnamed rhythm. As the examples mounted, as well as their significance (Elvis and Charles, Joplin and G-Unit, Muddy Waters and Kendrick Lamar, “Sing Sing Sing” and “It Don’t Mean a Thing”!), I began keeping a list — and then a Spotify playlist — for it seemed a remarkable yet widely unremarked musical thread. While my list is no doubt incomplete, it gestures to the breadth and depth of this rhythm’s presence in American popular music. It may also reflect certain biases in my listening: e.g., the surprising number of disco examples may say less about disco’s special predilection for American clave and more about the amount of disco I listen to. But that remains to be seen (and heard). I hope to enlist others in helping round out the picture. The point of this mega-mix is not to “drop the mic” on this subject and story but, rather, to invite people to listen along and add to the feedback loop that any DJ worth their salt aims to cultivate.

Further Rhythmic Disambiguation

I’d like to take some space here to say a little more about what makes this rhythm at once so distinctive and so deeply related to kindred rhythms. While American clave resembles several widespread rhythms that combine groups of 3s and 2s in order to produce a polyrhythmic effect, it is not nearly as widely distributed across the Americas, the African diaspora, and musical history as, say, what in Cuba would be called the tresillo:

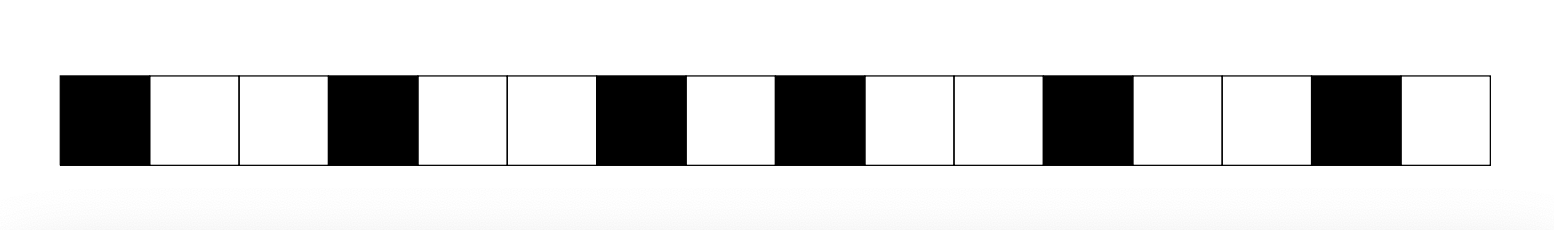

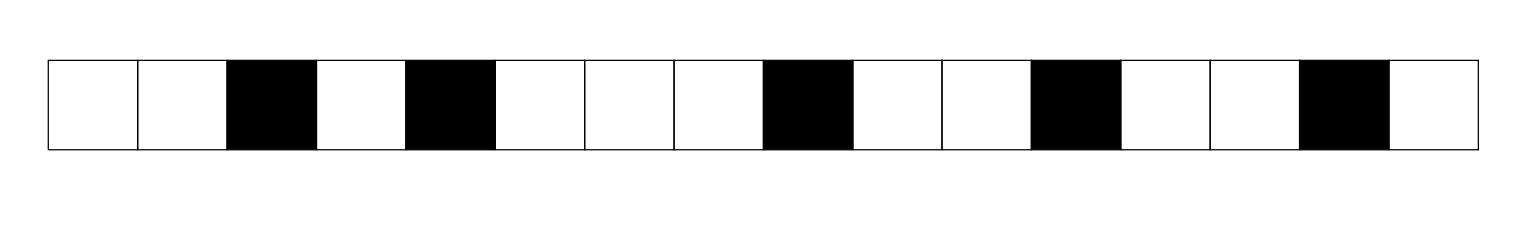

Figure: Tresillo (…follow the bouncing cowbell…)

The tresillo is a crucial cell in Cuban music. When combined with a steady 4/4 accent, it becomes the widely influential habanera (which many know today as dembow), and one could hear the Cuban clave, which we’ll come to in a moment, as containing the tresillo at two architectural levels (or degrees of subdivision).

But the tresillo is, of course, far more widespread than that. This 3+3+2 rhythm has been the prevailing beat of dancehall reggae since the 1990s (and far older Jamaican folk music), and it can be found in nearly all Caribbean popular and traditional music. Among the Ewe people of Southern Ghana, the rhythm has long been associated with dance and is known as gahu. Not surprisingly, the rhythm has been a part of African-American music since the beginning: it underpins the ring shouts of the Gullah Geechee communities of Georgia and South Carolina; some would call it the Charleston after James P. Johnson’s 1923 hit; the rhythm appears in many of Joplin’s rags, often contrasted with American clave sections; and Ernest Hogan’s first published composition, “La Pas Ma La” (1895), features a clear habanera-style tresillo, though in that case it may be as much a product of the growing international vogue for Cuban music as a nod to more local roots.

By adding a couple accents, or double-hits, it becomes a rhythm synonymous with the late 19th century cakewalk and, by extension, ragtime:

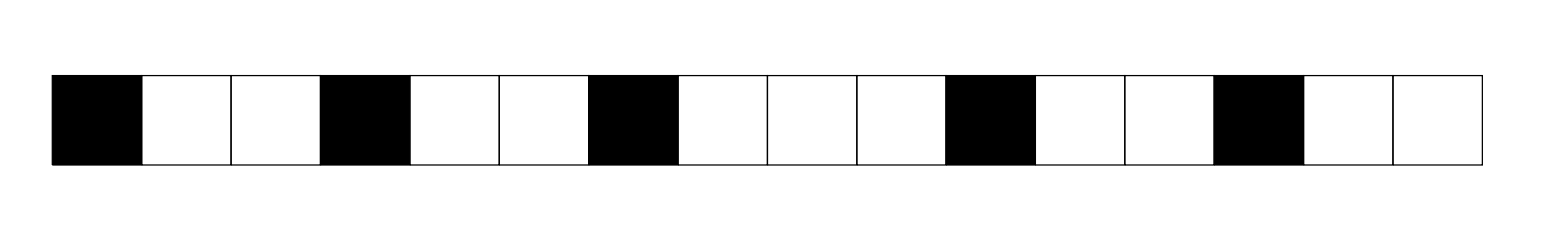

Figure: Cakewalk variation

This variation on the tresillo defines such paradigmatic ragtime compositions as Kerry Mills’s “At a Georgia Camp Meeting” (1897), one of the genre’s first published hits (which notably invokes the black sacred tradition). The rhythm clearly enjoyed popularity in earlier music of the 19th century, at once animating spirituals such as “Been in the Storm So Long” or minstrel show mainstays like “Zip Coon” (aka “Turkey in the Straw”), “Old Dan Tucker” (“Get Out the Way“!), or “Cotton-Eyed Joe” — some of which survive as “old time” tunes in the bluegrass and fiddle repertory, or as the stuff of country line-dances. Tellingly, although distinct from American clave, the “cakewalk” variation of tresillo is also often present in early country music as a vestige of ragtime’s broad early twentieth century resonance: hear it, e.g., in Jimmie Rodgers’s occasional turnaround flourishes on this 1936 rendition of “Blue Yodel #1 (T for Texas).”

It’s safe to say that the use of tresillo rhythms in U.S. music outnumbers American clave instances by a factor of scale. (Additionally, as noted in the article, I have yet to find a clear example of American clave in any pre-ragtime U.S. repertory.) American clave is, moreover, not nearly so widespread as Cuban clave. This is certainly true in the wider world, but is even the case in the United States where, among other instantiations, the Cuban clave has also been known as the “Bo Diddley beat” since the mid-50s—and as such can be heard in everything from garage rock to Brill Building pop to hip-hop.

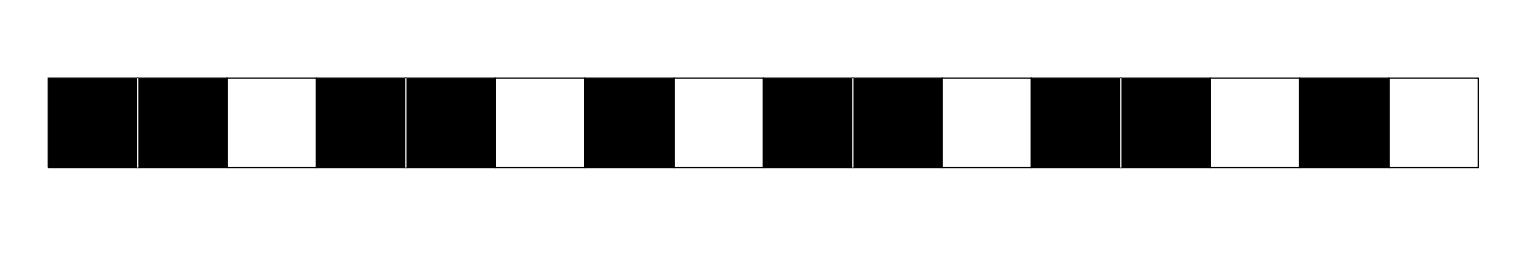

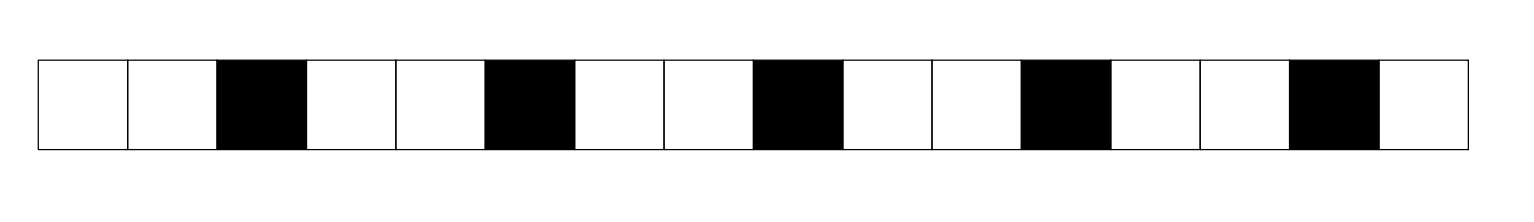

Figure: Cuban 3-2 clave (aka the Bo Diddley beat)

Another important difference between the Cuban clave and what I am calling American clave is that, at least in its “3-2” form, the Cuban clave begins its groups of 3s against 2s on the downbeat. As I learned when consulting Ghanaian master drummer Emmanuel Attah Poku at Tufts (as I recount in the article), traditionalists might argue that starting to play 3s against 2s on the downbeat is the “right” way, as also heard in the “double tresillo” here, another common pattern in African and Afrodiasporic music:

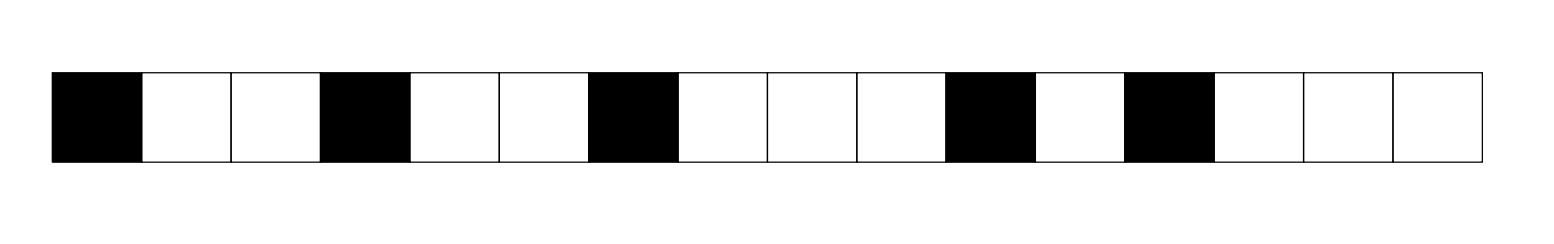

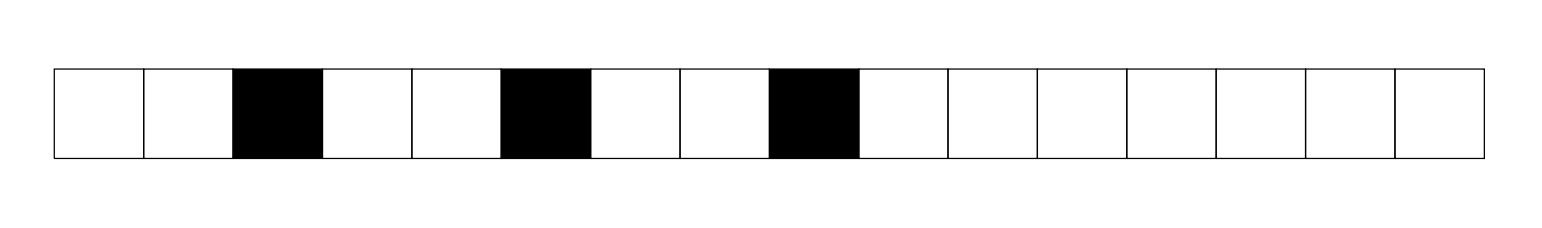

Figure: Double tresillo, starting “in the right place”

![]()

Instead, we might describe American clave as a double tresillo displaced by an eighth note, and it’s that crucial “offbeat” displacement that suggests we might be right to hear this particular polyrhythmic variant as a distinctively U.S. (or, forgive me, “American”) approach.

Figure: American clave, aka a displaced double tresillo

That said, in its 2-3 form, the Cuban clave also starts on the first offbeat just after the downbeat (i.e., displaced by an eighth note), and differs from the American version by a single, simple, but profound difference: the second accent arrives a sixteenth-note earlier. This difference results in a sense that the rhythm has two parts, a “2 side” and a “3 side” — asymmetrical complements crucial to Cuban clave’s underlying sense of push-and-pull or call-and-response, rather than the steady rolling character created by the more evenly-spaced accents of American clave.

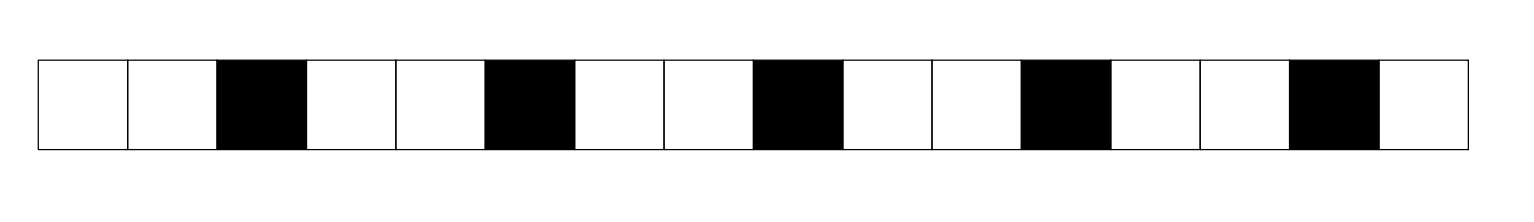

Figure: Cuban 2-3 clave

Though the two rhythms differ by a mere but meaningful sixteenth note, it seems remarkable that the American clave is exceedingly rare if not wholly absent in Cuba while, say, the Cuban clave has enjoyed great presence in the music of the United States.

Another big difference between the Cuban clave and the so-called American clave, as some aficionados might argue, is that in Cuban music the clave is a true rhythmic key around which everything is strictly fit and arranged, rather than simply a “beat.” (Of course, by that reasoning most uses of the “Bo Diddley beat” are also loose adaptations of this musical principle.) As I note in the article, this attitude of looseness or liberty seems to mark a particularly African-American approach to diasporic rhythm, especially in the post-ragtime era.

At this point, some perceptive reader-listeners and experienced drummers will have realized that what I’m calling American clave is the very same rhythm that some would call the Brazilian 2-3 clave. (This is not common terminology in Brazil, however, but among percussion pedagogues.) The so-called “Brazilian clave” in its 3-2 form, like the American clave, differs from the Cuban clave by a single but crucial sixteenth-note:

Figure: Brazilian 3-2 clave

Its “displaced” or 2-3 variant, which you may have heard played on a rimshot in many a bossa nova, is — on paper — indistinguishable from American clave (and, indeed, perhaps inextricable):

Figure: Brazilian 2-3 clave (and/or American clave)

Far as I can tell, Brazil thus offers the rare exception of a site outside the US where this particular rhythm is somewhat commonplace. But this rhythm’s popularity in Brazil may itself be a product of the transnational circulation of ragtime and jazz. As in the case of the United States, I have yet to find pre-ragtime examples of this rhythm in Brazil, though I would welcome knowing more about the local genealogy of this rhythm in places like Rio de Janeiro.

One final note (for now): in producing my list of examples and this mega-mix, I have insisted on a relatively rigorous musical definition of the figure in question in order to disambiguate from related but more common patterns: I have included only examples that feature at least 3, and usually 4 (if not 5 or more), “hits” beginning on the first off-beat of the measure. I.e.,

Figure: 3-count American clave

Figure: 4-count American clave

This leaves out the large number of recordings, from country to jazz, that use a looping 2+3+3 beat or what we might call an “inverse tresillo” — as heard in, say, Merle Travis’s “Guitar Rag” and many other country songs, or in Lee Morgan’s “Sidewinder” and its hard-bop ilk.

Figure: Inverse tresillo

Conclusion

Despite all this disambiguation and my attempts to frame American clave as distinctive in important ways, I want to close by stressing that this project aims to aid the audibility of a broader unity, not to support nationalist or racialist interpretations. As heard at various points in the mix, American clave enjoys remarkable co-presence with Cuban clave and tresillo rhythms of all sorts, sometimes in the same songs (a combination that, again, one mainly finds in the U.S.). This overlap is significant, showing how such rhythms co-mingle in the diasporic imagination and enable an audible cultural politics of polyrhythmic affinity. So, let’s listen along to all these historical actors and their shared offbeat accents. As 50 Cent reminds us, this is how we do. I’ve said enough about the this, whatever we want to call it. I hope these mixes help to reveal the we and the how.

American Clave Mega-Mix Tracklist

Charles Asbury, Keep in de Middle ob de Road (1891)

Ernest Hogan, All Coons Look Alike to Me (1896)

Scott Joplin, Maple Leaf Rag (1899)

Scott Joplin, Elite Syncopations (1902)

W.C. Handy, Memphis Blues (composed 1912)

Europe’s Society Orchestra, Down Home Rag (1913)

Jim Europe’s 369th Infantry “Hellfighters” Band, Russian Rag (1919)

Mamie Smith & Her Jazz Hounds, Baby, You Made Me Fall for You (1921)

Dick Hyman, Nickel in the Slot (composed 1923)

Jelly Roll Morton, Mamanita (1924)

Jelly Roll Morton, The Pearls (1924)

Ben Selvin and His Orchestra, Spanish Shawl (1925)

Fletcher Henderson, Sugar Foot Stomp (1925)

Fletcher Henderson, Alabamy Bound (1925)

South Street Trio, Cold Morning Shout (1926)

Bennie Moten and his Kansas City Orchestra, Kansas City Shuffle (1926)

Jelly Roll Morton, Beale Street Blues (1927)

Dallas String Band, Dallas Rag (1927)

Blind Blake, Southern Rag (1927)

Blind Blake, Come On Boys Let’s Do That Messin’ Around (1927)

Cannon’s Jug Stompers (Gus Cannon & Blind Blake), Madison Street Rag (1928)

Mississippi John Hurt, Ain’t No Tellin’ (1928)

Prater and Hayes, Somethin’ Doin’ (1928)

Louis Armstrong & His Hot Five, Struttin’ with Some Barbecue (1928)

Louis Armstrong & His Savoy Ballroom Five, Mahogany Hall Stomp (1929)

Jelly Roll Morton, Freakish (1929)

Roane County Ramblers, Everybody Two Step (1929)

Fletcher Henderson, Hot and Anxious (1931)

Fletcher Henderson, New King Porter Stomp (1931)

Duke Ellington, It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing) (1932)

Fletcher Henderson, Yeah Man! (1933)

Louie Bluie, State Street Rag (1934)

Willie “The Lion” Smith and His Cubs, There’s Gonna Be the Devil to Pay (1935)

Bob Wills & His Texas Playboys, Steel Guitar Rag (1936)

Benny Goodman, Sing Sing Sing (1938)

Glenn Miller, In the Mood (1939)

Blind Boy Fuller, Step It Up and Go (1940)

Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, That’s All Right (78 version) (1946)

Bob Wills & His Texas Playboys, Red Hot Gal of Mine (1947)

Bill Monroe and His Blue Grass Boys, Blue Grass Special (1947)

Muddy Waters, Rollin’ Stone (1950)

Flatt & Scruggs, Foggy Mountain Special (1954)

Thelonious Monk, Locomotive (1954)

Ray Charles, I Got a Woman (1954)

Elvis Presley, That’s All Right (recorded 1954)

Elvis Presley, Mystery Train (1955)

Chuck Berry, Rockin’ at the Philharmonic (1958)

Merle Travis, Cannon Ball Stomp (1960)

Fats Domino, Let the Four Winds Blow (1961)

Nina Simone, The House of the Rising Sun (1962)

Reverend Gary Davis, Twelve Sticks (1962)

John Fahey, Spanish Dance (1963)

John Fahey, The Last Steam Engine Train (1964)

Sam Cooke, Ain’t That Good News (1964)

The Valentinos, It’s All Over Now (1964)

James Brown, Out of Sight (1964)

Rolling Stones, I Just Want to Make Love to You (1964)

The Who, Out in the Street (1965)

The Beatles, What Goes On (1965)

Marty Robbins, Ribbon of Darkness (1965)

Willie Bobo, Boogaloo in Room 802 (1965)

Willie Bobo, Shotgun / Blind Man (1965)

Cannonball Adderley Quintet, Games (1966)

Elvis Presley, Paradise, Hawaiian Style (1966)

Doc Watson, Victory Rag (1966)

Doc Watson, Dill Pickle Rag (1966)

Max Ochs, Raga – Pt. 1 (1967)

The Doors, Love Me Two Times (1967)

Merle Travis, Cannonball Rag (1968)

Merle Haggard, Mama Tried (1968)

The Beatles, I Will (1968)

Dr. John, Danse Fambeaux (1968)

Steppenwolf, Magic Carpet Ride (1968)

The Flying Burrito Brothers, My Uncle (1969)

Leo Kottke, The Driving of the Year Nail (1969)

Leo Kottke, Busted Bicycle (1969)

Chicago, I’m a Man (1969)

Kool & the Gang, Give It Up (1970)

Credence Clearwater Revival, Lookin’ Out My Back Door (1970)

Ike Everly (on theJohnny Cash Show), Cannonball Rag (1970?)

Chet Atkins and Jerry Reed, Cannonball Rag (1970)

Billy Garner, I Got Some Pt 1 (1971)

Booker T. & the MGs, Melting Pot (1971)

Stevie Wonder, Superstition (1972)

The Trammps, Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart (1972)

Barrabás, Woman (1972)

Dr. John, Mess Around (1972)

Gram Parsons, Ooh Las Vegas (1973)

The Spinners, Sitting on Top of the World (1974)

Gwen McCrae, Move Me Baby (1974)

Keith Jarrett, The Köln Concert, Part I (1975)

The Flying Burrito Brothers, Cannonball Rag (1975)

Black Sabbath, Megalomania (1975)

Ronnie Laws, Always There (1975)

Double Exposure, Ten Percent (1976)

Stevie Wonder, I Wish (1976)

Marvin Gaye, I Want You (1976)

Average White Band, Cut the Cake (1976)

Herbie Hancock, Doin’ It (1976)

George Benson, Nature Boy (1977)

Bee Gees, Night Fever (1977)

Gloria Gaynor, I Will Survive (1977)

Sylvester, You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) (1978)

Jackie Moore, This Time Baby (1979)

Candido, Thousand Finger Man (1979)

The Whispers, And the Beat Goes On (1979)

Pat Metheny, New Chautauqua (1979)

Instant Funk, Slap, Slap, Lickedy Lap (1979)

Loleatta Holloway, Love Sensation (1980)

Richie Havens, Going Back to My Roots (1980)

Dolly Parton, 9 To 5 (1980)

Rick James, Give It to Me Baby (1981)

Morley Loon, Amendo Na Nooch (1981)

Ricky Skaggs, Highway 40 Blues (1982)

Yes, Changes (1983)

Culture Club, Miss Me Blind (1983)

Van Halen, Jump (1983)

Deniece Williams, Let’s Hear It for the Boy (1984)

Strafe, Set It Off (1984)

Run DMC, Sucker MC’s (1984)

Farley Jackmaster Funk, Aw Shucks (Let’s Go) (1985)

Tony Rice, When You Are Lonely (1985)

George Michael, I Want Your Sex (1987)

George Michael, Faith (1987)

Rhythim Is Rhythim, Strings of Life (1987)

Six Brown Brothers, Battery Acid (1988)

Chaka Khan, Life Is a Dance and This Is My Night (1989)

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Ali Da Malang (1991)

Second Phase, Mentasm (1991)

Moby, Go (1991)

Marky Mark & the Funky Bunch, Good Vibrations (1991)

Eric B & Rakim, Don’t Sweat the Technique (1992)

Daft Punk, Da Funk (1995)

Chet Atkins, Jam Man (1997)

Don Rigsby, Wings of Angels (1998)

Mos Def, Fear Not of Man (1999)

Grandmaster Flash (+First Choice + party in the back), Salsoul Jam 2000 (2000)

Jagged Edge (feat.Nelly), Where the Party At (2001)

Kelis, Perfect Day (2001)

Daft Punk, Something About Us (2001)

Daft Punk, Short Circuit (2001)

The Game (feat. 50Cent), How We Do (2005)

Jack Rose (and Glenn Jones), Linden Ave Stomp (2008)

Tony Trischka, John Cohen’s Blues and Rainbow Yoshi (2008)

Glenn Jones, Barbecue Bob in Fishtown (2009)

The St. Regis String Band, Sally in the Chicken Coop (2009)

Buge Cage & Willie B. Thomas, Bugle Call Blues (2011)

Daft Punk, Get Lucky (2013)

Daft Punk, Touch (2013)

Shakey Graves, Tomorrow (2013)

Kenny Sasaki & the Tiki Boys, Hulabilly Baby (2014)

Chris Stapleton, Traveller (2015)

Coldplay, Adventure of a Lifetime (2015)

Kendrick Lamar, Alright (2015)

The Weeknd, Can’t Feel My Face (2015)

William Tyler, Kingdom of Jones (2016)

Calvin Harris (feat.Future, Khalid), Rollin (2017)

Beck, Colors (2017)

Blondie, Fun (2017)

Janelle Monae, Screwed (2018)

Marshmello, Happier (2018)

Disclosure (feat. Fatoumata Diawara), Ultimatum (2018)

Makaya McCraven, A Queen’s Intro (2018)

Steve Gunn, New Moon (2018)

Chance the Rapper (feat. John Legend), All Day Long (2019)

Common, My Fancy Free Future Love (Tom Misch Remix) (2019)

Mac Miller, Blue World (2020)